It’s high time Canada looked beyond the U.S. for trade opportunities

There’s a world of export markets out there, if only Canadian businesses could lift their sights from the domestic and U.S. markets

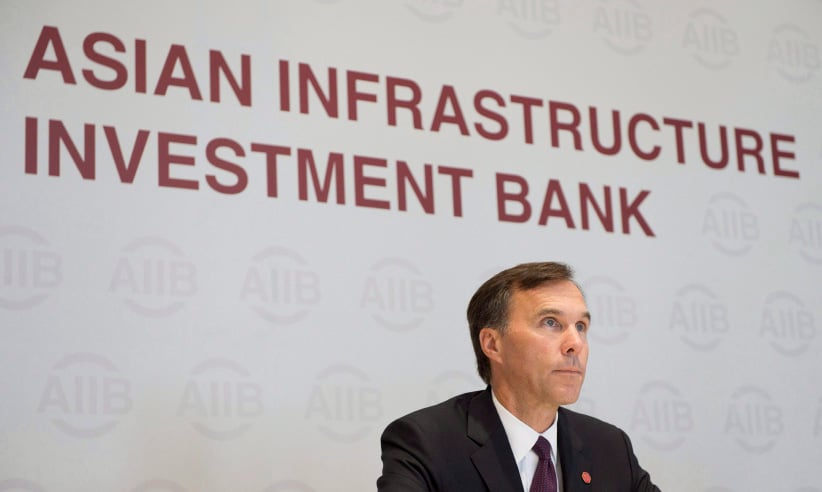

Canadian Minister of Finance Bill Morneau during a news conference at the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. (Adrian Wyld/CP)

Share

In 2012, Mark Carney, the former Bank of Canada governor, challenged the country’s exporters to break it off with their sugar daddy. “The combination of overexposure to the U.S. market and under-exposure to faster-growing emerging markets is entirely responsible for Canada’s further loss in world market share over the last several years,” he said in a speech to the Greater Kitchener Waterloo Chamber of Commerce.

They didn’t listen.

Five years later, the contours of Canada’s commercial ties with the rest of the world are about the same as they were when Carney punctured the myth that Canada is a great trading nation. Last year, Canadians invested $68.3 billion in Barbados, a tiny Caribbean country that is a haven for tourists and tax dodgers. That’s almost as much as Canada invested in all of Asia, home to most of the world’s fastest growing economies. But you see, doing business in that part of the world is tough, and they don’t speak a lot of English. Faced with those challenges, much of Canada’s money would rather go to the beach.

No investor would put all of his or her money in the U.S. and Canadian stock markets, yet most Canadian executives are content to do all of their business at home or in the United States. It’s an easy path to profits when times are good. But one of the reasons Canada’s economy has struggled to regain its pre-crisis form is that thousands of companies were wiped out by America’s Great Recession. And now, Canada’s short-term prosperity will be determined by the whims of President Donald Trump, who jerked around Canadian stock markets and the currency this week by sending conflicting signals about his intentions for the North American Free Trade Agreement.

READ MORE: What if Canada and Mexico said no to renegotiating NAFTA?

The U.S. will forever be Canada’s biggest trading partner. Research shows that proximity determines the overall direction of trade more than any of factor. But truly great traders maximize their closest markets, and then chase opportunities elsewhere. As countries such as Germany and Australia seized on China’s rapid rise from poverty, Canada barely got in the game. According to calculations by Export Development Canada for Maclean’s, Canada’s share of Chinese merchandise imports was a mere 1.3 percent in 2012, compared with 4.8 percent for Australia and 5.2 percent for Germany. Those shares haven’t changed much in the years since. Canada has managed a small improvement, pushing its share of China’s imports to 1.4 percent in 2016, while Australia was at 4.3 percent and Germany was 5.3 percent.

Meanwhile, China, Mexico, South Korea and others pushed their way into the U.S. at Canada’s expense: imports from Canada represented 11.6 percent of America’s total in 2016 compared with 13.2 percent in 2010, according to EDC’s calculations.

All of this has come at huge opportunity cost, the term economists use to describe what could have been. The value of Canadian merchandise exports only recently returned to pre-recession levels. The slow recovery meant fewer jobs and less wealth. Weaker demand was part of the problem, but the bigger issues were greater competition in the U.S. and too little exposure to the rest of the world. The result: Canada’s share of global exports has fallen to about 2.5 per cent from 4.5 percent in 2000.

Former prime minister Stephen Harper talked about shifting Canada’s attention to Asia and other emerging markets. But his laissez-faire approach to trade, and his occasionally antagonistic relationship with the Chinese government, mostly failed. Harper negotiated a free-trade agreement with South Korea, yet Canada’s share of merchandise imports by that country are about the same as they were before it came into force in 2015.

Trudeau is being more aggressive. Finance minister Bill Morneau was in China this week to underline Canada’s seriousness about doing a trade deal with the world’s second-biggest economy. While Harper refused to join China’s new Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, Morneau used his latest budget to set aside the $256 million that will be required to the join the institution. The budget also set a target of increasing exports of goods and services by 30 per cent by 2025. Several of Trudeau’s ministers have visited India, another big Asian economy with which the current government has pledged to do a trade agreement.

RELATED: How much will the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank cost Canada?

If Trudeau is serious about diversifying Canada’s trading relationships, he will have to pursue the goal relentlessly.

It’s not that Canadian business is universally indifferent to international opportunity. Investment is an important indicator of international engagement because commerce no longer is as simple as making something in one place and shipping it to another. Countries such as China and India often demand a local presence as a condition of access to their huge markets. Investment in China averaged about $13 billion in 2015 and 2016, an increase from $8 billion in 2014. But that still is a trivial amount. Canadians invested $474.3 billion in the U.S. last year, according to Statistics Canada.

The investment figures show why Trudeau will struggle to achieve his trade goals. Faced with the prospect of a protectionist president, and overwhelming evidence that best long-term opportunities are in Asia, Canadians appeared to become even more focused on the United States. When Carney delivered his clarion call on trade in 2012, the U.S. represented 39 percent of Canada’s total international investment. Last year, it was 45 percent. To paraphrase Trump, “Sad!”