It’s a scary world, but for investors fear can be a dangerous emotion

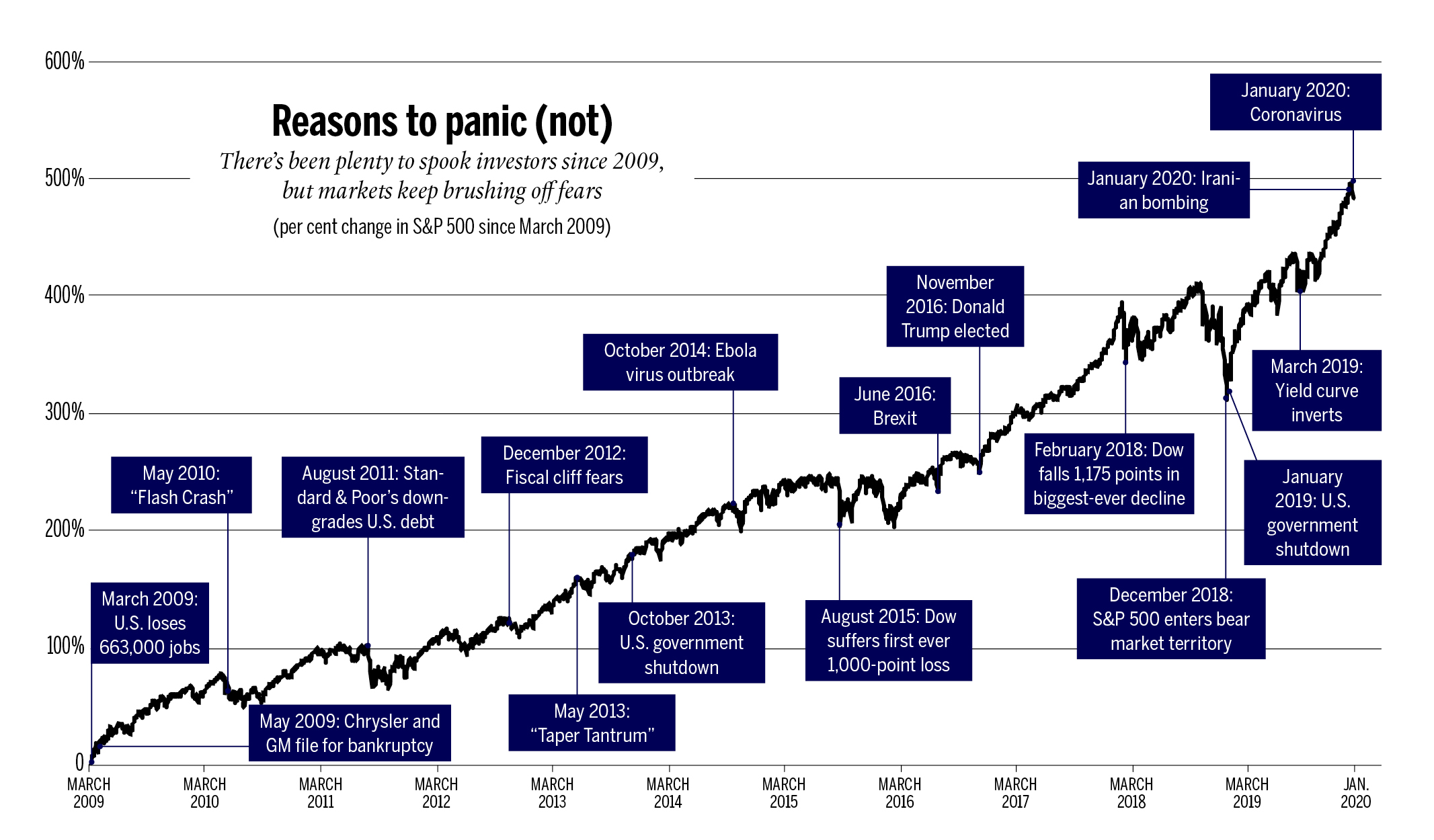

Stock markets tumbled after news of the coronavirus’s spread. But we’ve been here before and markets always bounce back. Experts share their advice for the worriers.

A woman with a facial mask passes the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) on Feb. 3, 2020 at Wall Street in New York City. (Johannes Eisele/AFP/Getty Images)

Share

When news broke in late January that the Chinese coronavirus had spread to multiple countries, including Canada, stock markets tumbled. Investors feared the fallout across a wide range of sectors, from travel and tourism to retail and restaurants, and the impact a broad sales slowdown could have on global economic growth.

A similar fear led to panic selling when the Ebola virus spiked in 2014. Market anxieties also took over when Donald Trump was first elected U.S. president in November 2016, when the closely watched yield curve inverted last year, and during the worst of the recent U.S.-China trade war.

READ: Here’s why investing at the start of the year is so important

In other words, we’ve been here before. After each collapse in stock prices, markets roared back relatively quickly. North American markets regularly hit new highs in late 2019 and early 2020. Still, despite the upward trajectory of markets over the long term, some investors continue to sit on the sidelines, expecting the worst.

“There’s a certain breed of investor who always has a pessimistic view,” says Dan Bortolotti, a portfolio manager and financial planner with PWL Capital in Toronto. “They’re scared when markets are up, fearing what goes up must come down, and scared when they’re down, fearing they’ll fall further. Basically, they’re always worried the markets will go down.”

Worrying about how markets will perform is human nature, particularly among investors who experienced the 2008-09 global recession, but constant trepidation can wreak havoc on a person’s investment portfolio. Investors who wait for the right time to buy, or sell, can miss out on significant gains over the long run. On the flip side, those who sell in a panic might later regret it. A good example is the major market sell-off that happened in late 2018 and the subsequent rebound that followed just weeks into 2019. The U.S. S&P 500 Index is up more than 40 per cent from its December 2018 low.

Trying to time the market is the wrong way to invest, says Brian Belski, chief investment strategist at BMO Capital Markets. “Nobody can time the market,” Belski says. “The minute you think you can time the market . . . is the minute you shouldn’t be in the market.”

Still, investing is part math and part sentiment, and it’s the human emotion part of the equation that often gets investors into trouble. Investing based on emotion, such as greed or fear, drives investors to buy when markets rise or sell when they drop—or do nothing, which can also have a long-term impact on savings, says Lisa Kramer, a professor of finance at the University of Toronto.

“It’s a fool’s errand to try to predict what markets will do,” says Kramer, who studies investor behaviour. “The best advice is for investors to develop a portfolio allocation that they’re comfortable holding through the best of times and the worst of times . . . and not conditional on what they think will happen next. The ‘buy and hold’ strategy is really the best thing going.”

The task is easier said than done when we consider the cognitive biases that investors are susceptible to. Take overconfidence, for example. Some investors believe they’re good stock pickers and take risks they can’t afford on hot stocks or sectors. Consider here the number of confident cannabis investors who have been burned in recent months. Another bias is loss aversion: the pain of losing money is much worse than the positive feeling of seeing gains. Loss aversion keeps many investors holding huge chunks of their portfolio in cash, earning little or no interest.

READ: Real estate photos are distorting reality, frustrating would-be home buyers

Another red flag is confirmation bias: investors seek out or interpret information that supports their existing market beliefs. The risk is ignoring facts that could help them make smarter investment choices. It’s a bigger problem in today’s digital society, where algorithms on sites such as Facebook feed users information based on what they’ve already viewed, warns Tea Nicola, co-founder and CEO of Vancouver-based WealthBar Financial Services. “If you’re reading certain things in your social media feed, chances are you will be fed more things on that subject, but it’s not necessarily the whole story,” she says. “As an investor, you have to be hyper-vigilant.”

To try to keep emotions out of the mix and focus on the longer term, Bortolotti of PWL Capital recommends people invest in stages. For instance, someone investing the proceeds left over from a regular paycheque might add money to the markets once a month, while a person with a lump sum—from an inheritance or home sale, for example—might consider investing in two or three stages, over a few months. He also recommends investing the money on a pre-set schedule, and sticking to it.

“You might not end up with a better result than if you invested it all at once, but it will probably be less stressful because you won’t feel like you’re going all in on a single bet,” Bortolotti says. “Just keep contributing and rebalance your portfolio as necessary. That’s not market timing; that’s risk management.”

Investors also need to make sure that they have the right mix of assets, such as stocks, bonds and cash, to meet their financial goals, says Kash Pashootan, CEO and chief investment officer at First Avenue Investment Counsel Inc. in Toronto. Generally speaking, people in their 30s with long careers ahead of them can usually take more risks in the stock market than 65-year-old retirees on fixed incomes.

Investors, regardless of age and asset mix, also need to be ready and able to withstand “material declines” in a market downturn, when it eventually comes, Pashootan says. “To me, the biggest risk now isn’t an upcoming recession. It’s complacency in investors’ portfolios,” he says. “The single most important thing we do for clients right now, and what investors can do for themselves, is to understand how their portfolios can behave . . . in the next negative market and decide if they can live with that, or not. If not, adjust now.”

This article appears in print in the March 2020 issue of Maclean’s magazine with the headline, “Panic and portfolios don’t mix.” Subscribe to the monthly print magazine here.