The dark side of the renovation boom

Canadians spend billions a year on renovations. But our love affair with fix-ups has put households—and the economy—at risk.

Share

The hit Canadian TV show Property Brothers follows a formula as rigid as a newly sistered floor joist. Real-life twin brothers Drew and Jonathan Scott, the former a real estate agent and the latter a contractor, meet a couple searching for a new home. After listening to their list of “must-haves”—soaker tub, gourmet kitchen, ensuite bathroom—they tease the prospective buyers by wowing them with a swish pad far beyond their price range. Next, it’s off to view a more affordable but dumpier abode that inevitably draws such reality TV-esque observations as, “When I walked in, I was, like, no.” Unfazed, the winsome brothers–tall, stubbly faced and each capped with a lustrous head of hair–transform the ugly duckling into a magazine-worthy swan through an epic renovation (compressed to the show’s 60-minute run time), making sure to encounter a few dramatic surprises and setbacks along the way.

Now in its fourth season, Property Brothers airs in Canada on the W Network and on HGTV in the United States, where it’s among the U.S. network’s top-rated programs. Brother vs. Brother, another Scott Brothers show, is also a favourite with U.S. audiences. The same goes for W Network’s Love It or List It program. In fact, three out of every four HGTV Canada shows are picked up in the U.S., according to a HGTV Canada spokeswoman. In other words, after all those years fretting about CanCon, we’re now inundating millions of Americans with our non-flag-flying front porches and chesterfield-harbouring living rooms without even realizing it.

The growing universe of made-in-Canada home reno shows, from Deck Wars to Holmes on Homes, is only the most visible example of the country’s preoccupation with redesigns, remodels and wholesale redos. Others include the ubiquitous Dumpster bins dropped on lawns across the country, the decision by U.S. home improvement giant Lowe’s to follow Home Depot into Canada back in 2007, and the seemingly ever-present sound of the neighbour and his trusty circular saw embarking on his latest weekend project.

Total spending associated with residential renovations and repairs has more than doubled since the late 1990s to nearly $64 billion last year, or nearly four per cent of Canada’s GDP, according to a recent report from Altus Group, a Toronto-based property consulting firm. And it has almost nothing to do with a growing population or the increase in the number of houses over that time. In fact, three-quarters of the gains can be directly attributed to Canadians’ willingness to open their wallets ever wider, if it means getting a cathedral ceiling in the master bedroom or a heated floor in the basement loo.

How did we get to be such an indulgent and inward-focused lot? Our white-hot housing market had a lot to do with it. Most new homebuyers contemplate at least a few updates before moving in, while sellers now routinely spruce up their properties before listing them, in the hopes of fetching a higher price. And since money is cheap, thanks to record-low interest rates, it has never been easier for Canadians to borrow to get that new breakfast-nook addition or backyard patio. But mostly, it’s driven by the premise that thousands spent on new floors and fixtures is an “investment,” as opposed to mere conspicuous consumption. A 2013 survey by the popular home-remodelling website Houzz found that 60 per cent of Canadians cited “increasing value” as the key motivation to renovate—just as on Love It or List It, when the homeowners learn that $90,000 worth of renos to their tired bungalow just increased its “expected value” by—wait for it—$120,000.

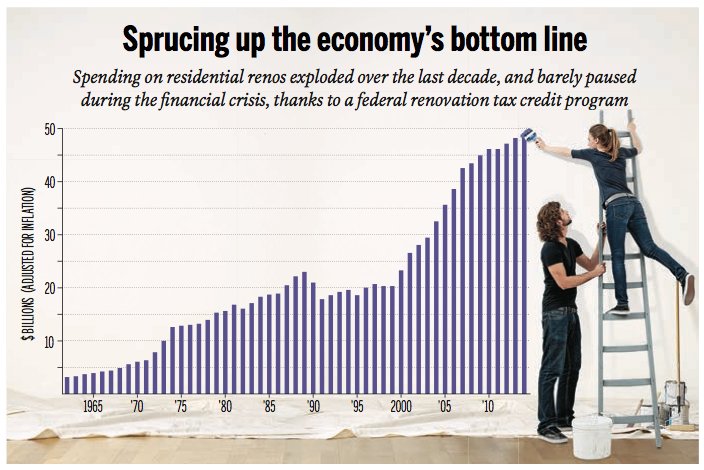

Yet, while all that flying sawdust juiced Canada’s economy, some fear that the remarkably resilient sector (unaffected by the 2009 recession, thanks in part to Ottawa’s home renovation tax credit) could prove to be a house of cards. A hike in interest rates or a slump in home prices—or, more likely, both together—promises to dramatically curtail renovation spending, since homeowners would no longer be able to convince themselves that splurging for tropical hardwood floors will, magically, net them a huge return. Nor is it clear whether the flurry of spending has improved the country’s aging housing stock, or merely painted it several times over with truckloads of expensive lipstick.

It’s the age-old story of wanting to keep up with the Joneses—except that now, the Jones family is a perky young couple armed with a pile of borrowed cash and a pair of grinning TV hosts.

Canadians’ love affair with home renovations is second only to our seemingly insatiable lust for owning real estate—and the two are linked at the hip. A report by TD Economics last year found that renovation spending has increased, on average, at a rate of seven per cent a year since 2003, and that roughly half the growth can be directly attributed to rising numbers of home sales and soaring prices. The reason is simple: In a hot housing market, shelling out $2,000 for a new granite countertop could add another $10,000 or more to the value of a house, providing the buyers fall in love with the kitchen. “In recent years, the idea of staging a house and doing reasonably substantial changes to a house prior to listing has become more the norm in the resale world,” says Peter Norman, Altus Group’s chief economist. “There’s a lot of revamping of kitchens and bathrooms and other types of projects to get a $900,000 house up into the $1.2-million range.”

Norman calls it the “HGTV effect,” and it applies equally to buyers. Many young Canadians shopping for their first home have found themselves squeezed out of hot markets in cities such as Toronto, Vancouver and Calgary. So, instead of trying to compete in vicious bidding wars for “move-in-ready” houses—earlier this year a renovated semi-detached home in Toronto’s west end sold for $210,000 over the asking price, after getting 32 offers—many opt to buy older fixer-uppers and renovate themselves. Depending on the house, fixes can be anywhere from cosmetic updates to complete gut jobs. No wonder Canadians spend, on average, $21,000 more on their homes in the year following the purchase of a house, according to data from the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corp.

Flipping houses has become another lucrative pastime in many cities. Buyers—often contractors—scout out overlooked, rundown homes in otherwise desirable neighbourhoods, and put in a few months’ work before turning around and selling the property for substantially more than they paid for it. Sometimes the renovations are truly spectacular, but, more often than not, it’s a case of throwing up some Ikea cabinetry on the kitchen walls and laying cheap laminate flooring directly over the concrete pad in the basement.

It’s not only buying or selling their houses that prompts homeowners to spend. Merely watching house prices inch higher in a hot market is sufficient. Economists call it the “wealth effect,” and TD cites studies that show for “every $1 increase in wealth due to home-price appreciation, households go out and spend an additional nickel—a chunk of which ends up in renovations.” Though they may not be as noticeable to neighbours, Norman says, most renovations are smaller jobs in the $3,000-to-$7,000 range—finishing a basement, knocking down a wall or two. He adds that Canada’s Baby Boomers have contributed to the reno boom because many are opting to stay in their homes, rather than downsize to a condo. “A lot of renovations are aimed at adapting homes for those pre-retirement years,” he says.

It seems there’s a never-ending list of things that need attention. The last big building boom in Canada occurred in the mid-1980s, meaning that many of those houses are now reaching the age where updates are required— and not just because brass fixtures and billowy window treatments are no longer in vogue. Blaine Swan, a home inspector and the president of the Canadian Association of Home and Property Inspectors, says many structures erected in the era are suffering from mould and other moisture-related problems, because builders had begun increasing levels of insulation in, and airtightness of homes, but didn’t always improve ventilation systems. “We started living in a plastic bag,” he says.

Even the country’s recent condo boom is a driver. While most of the soaring towers erected in cities such as Toronto, Calgary and Vancouver are still relatively new, the renovation cycle for units tends to be shorter, since part of the appeal of condo living is a swish, contemporary design. And, as new condo construction lures people back downtown, prompting the opening of new restaurants, coffee shops and yoga studios, it is simultaneously raising the value of older inner-city homes—the ones most likely to be in need of the biggest upgrades.

With tearing down and rebuilding property now a national pastime, it’s little wonder TV producers have tapped the reno trend for reality-TV treatment. Christine Shipton, the vice-president of original content at Shaw Communications’ media division, which owns HGTV Canada, says the genre really took off in earnest about three or four years ago—just as Canada’s housing market resumed its skyward climb following a brief lull during the recession. Prior to that, she says, most of the shows on the network were more “decorator-centric,” focusing on furniture, paint colours and clever ways to spruce up the patio. Those shows that did focus on renovations tended to target DIYers, following the sort of how-to format pioneered by PBS’s This Old House back in the 1980s. Even Mike Holmes, whose popular Holmes on Homes show first aired in 2001, was initially liked by audiences mainly because of his expertise and the way he verbally disembowelled the shoddy work of the contractors and developers who had preceded him.

These days, by contrast, the renos and the homeowners undertaking them have taken centre stage. “It’s not just the personalities of the hosts,” says Shipton. It’s also about “the people who are renovating their homes, what their stories are, what the stakes are for them and how it changes their lives.” In other words, renos make for good television, with their unexpected surprises, high stakes and big payoff at the end. Which is fine, as long as those contemplating real-life renos realize that most projects featured on TV aren’t simple weekend jobs, and they’re not mortgaging their future in the process.

Sadly, however, that appears to be just what Canadians are doing. A Bank of Canada report two years ago found an average of $8 billion in annual renovation spending between 1999 and 2010 was financed through debt, including loans borrowed against the existing value of real estate through home equity lines of credit, or HELOCs. The Houzz survey found that a growing number of Canadians borrow to pay for their renos, with 34 per cent saying they would take out a line of credit in 2013, compared to 14 per cent a year earlier.

Call it the dark side of the country’s reno obsession. At a time when Canadians are awash in mortgage and other debt, owing an average $1.63 for every disposable dollar earned, many are gleefully doubling down on a single, relatively illiquid asset class: housing. And they’re doing so at a time when many observers believe it’s hugely overvalued. Debt-rating agency Fitch estimates Canadian home prices are, on average, 20 per cent too high; other forecasts are even more dour. If there’s a significant correction, or a crash, homeowners will not only be faced with both the declining value of their homes, but paying back tens of thousands to the bank on top of it—potentially leaving them on the hook for more than their homes are worth.

It’s not just a risk to those renovating, but the economy as a whole. The debt-fuelled reno trend has played a major role in artificially inflating the price of houses in Canada, as eager buyers take advantage of cheap mortgage rates to compete in bidding wars for showpiece homes, each offering tens of thousands more than the next. Nor is it just people who plan on living in the homes who are responsible for soaring prices. In cities such as Toronto and Vancouver, buyers often find themselves competing head-to-head with contractors or other real estate professionals keen to buy cheaper properties that can be renovated and flipped at a huge profit. Add it all together and it’s akin to throwing gasoline on a raging brush fire—an inferno Ottawa has tried to cool four times by tightening restrictions on government-backed mortgage insurance, albeit with little effect.

The concern is what happens to consumer spending, and the economy it supports, if the housing bubble pops. “Household spending on consumption and home renovation can become vulnerable to house-price shocks,” concluded the Bank of Canada, noting that countries that had the biggest increases in home prices and debt-to-income ratios in the run-up to the 2008 crash experienced the biggest hit to spending during the recession that followed. Put another way, Canadians will suddenly feel poorer and more indebted, prompting them to snap their wallets shut. Even a modest correction could have a significant impact, given housing and the various industries that support it make up a quarter of Canada’s GDP, by some estimates. “The psychology would change, such that a new kitchen won’t so easily be justified as an ‘investment’ when property values are falling,” says Ben Rabidoux, the president of North Cove Advisors, a research firm. He adds that spending would be further affected by the challenge of borrowing money, since “HELOC and cash-out refinancing lending would tighten,” as the assets securing the loans—people’s homes—fall in value.

At least Canadians could comfortably wait out the carnage in their well-appointed castles, right? Maybe not. Though rarely talked about, there’s mounting evidence to suggest Canadians are mostly loading up on cosmetic improvements (the type most often depicted on TV shows) and ignoring more important fixes that would make their homes more comfortable and energy-efficient in the long term. Russell Richman is a professor of building science at Toronto’s Ryerson University. A few years ago, he bought a dilapidated century-old home in Toronto’s east end and made his $300,000 reno a real-world experiment in sustainable building practices. “We did really easy things, like high insulation levels, really good windows, tight air-leakage ratings, an efficient [radiant in-floor heating] system and LED lighting,” he says, adding that the energy-efficient extras contributed between $40,000 to $60,000 to the final price tag. “We operate the house in a tree-hugger, nuts-and-berries fashion. I have the windows open most of the summer while my neighbours close the windows on June 1st and put on the AC.” The result? A recent test comparing his house to his neighbour’s showed he used a fraction of the air conditioning in the summer and about half the energy to heat the house during the winter. “Five to 10 years and beyond, you will actually start to make money on this type of investment.”

Unique among his renovation-happy neighbours, Richman fears we’re collectively missing an opportunity to upgrade the country’s aging housing stock, just as many predict energy costs are poised to spike. “At the end of the day, most of the stuff we see in the pop-culture media is house porn,” he says. “But, to me, everything you don’t see in a house is equally as important as what you do see. If you spend $5,000 on the floors, it should be in our psyche to spend $5,000 behind the drywall. We need to move toward that.”

Canadians also need to move away from the idea that renovations are an easy way to make money. Those who’d balk at borrowing thousands to bet on stocks think nothing of doing so to gamble on home improvements, reasoning they’ll recoup the cost or even earn a profit. But earning a return on your renos only works if you undertake the right ones, then sell immediately in a rising market. (Those brand-new floors will be a lot less valuable after being subjected to the family dog for a few years.) Even then, there are no guarantees—other than laying the groundwork for some future TV-show makeover, of course.