Why movement is critical to learning

The way instruction is delivered in post-secondary institutions doesn’t always take into account the brain-body connection. In fact, it can reduce students to ‘brains on sticks.’

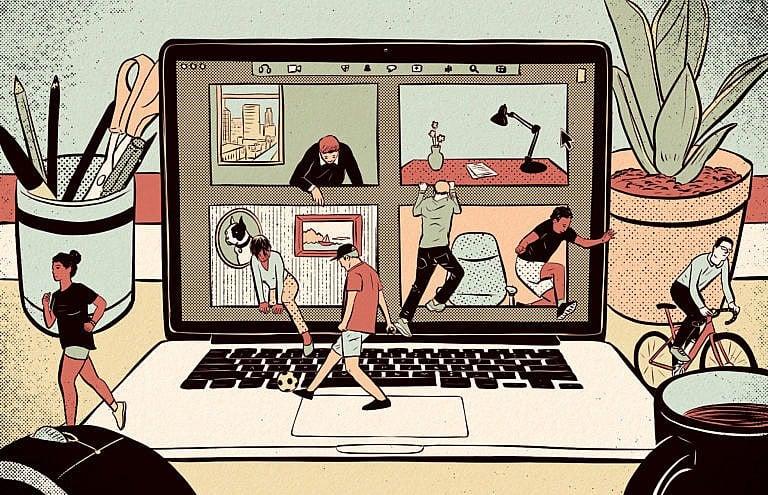

(Illustration by Jarett Sitter)

Share

Naila Syed misses movement.

When I chatted with her in May, the second-year journalism student at Centennial College in Toronto, who I taught in the winter 2021 semester, spoke fondly about her pre-pandemic classes. “We would always go out,” she says, referring to class activities that required her and her fellow students to physically track down sources for a story or photograph. “Even if you’re physically in class, sitting there for three hours or four hours is not ideal.”

Science suggests Syed is right. There’s a robust body of research that links physical movement with better learning outcomes. “Study after study shows physical activity activates the brain, improves cognitive function, lowers anxiety and helps students focus, engage and be interested,” says Shelley Murphy, course lead in the department of curriculum, teaching and learning at the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education at the University of Toronto. “Even short, frequent movement breaks can have a huge impact on learning, and on students’ mental and physical health.”

However, over the past year and change, students have had very few opportunities to experience movement in the classroom. Rolling lockdowns and social distancing rules have meant we’ve all been staying home and away from other people as much as possible. As a result, students of all ages mostly sat in front of screens while learning. And while schools are now considering how to safely reopen campuses, many programs and students will opt to continue distance education. But that doesn’t mean movement must be sacrificed.

Exercise increases blood flow throughout our bodies, including to our brains, which actually makes it easier to think. So a jog, a hike or even a quick stretch helps us absorb information. “In general, we think differently when standing or walking, and when we can move around to study something that interests us,” says Susan Hrach, director of the faculty centre and professor of English at Columbus State University, and author of the new book Minding Bodies: How Physical Space, Sensation, and Movement Affect Learning. “Mobility offers a boost for our cognitive processes.”

[contextly_auto_sidebar]

But, Hrach says, the way instruction is delivered, particularly in post-secondary institutions, doesn’t always take into account the brain-body connection. In fact, it can sometimes unintentionally reduce students to “brains on sticks,” as California-based environmental activist and author Joanna Macy first put it. That metaphor, says Hrach, “is an apt visual image to convey the perception that our heads are the only parts of our bodies that matter for thinking. What many people haven’t understood is that our whole bodies shape cognitive processes.”

Educators have been faster to incorporate movement into lessons for children, using strategies like tossing a ball while learning vocabulary, and singing and dancing to learn math. But older students are still often asked to sit quietly through a lesson or lecture. This might be the most efficient way for an instructor to disseminate information, but it’s not necessarily the most effective way for a student to receive it, whether in-person or online, says Anne-Marie Scott, the deputy provost of academic operations at Athabasca University.

According to Hrach, this emphasis on efficiency is a by-product of Industrial Age education. “Adults are better at tolerating these expectations, but humans on the whole are built to move,” she says. “Just recall pre-pandemic all-day meetings and conferences; even hard-core academics would start complaining by the end of the day about our butts hurting. It’s ironic we didn’t consider the obvious solution: to exchange information in a different way.”

That’s what Murphy’s research has found, too. Before the pandemic, she conducted a study with the students in her mental health and special education courses. She had them do three things: turn their phones off and put them away for the duration of the class; participate in mindfulness practices; and participate in one 10-minute movement break per three-hour class. “Student after student talked about how it got the energy going, helped them to focus more, [gave them something] to look forward to and helped them to build community with each other because it was fun,” she says. “They noticed changes in their behaviour, their attention and their mental health and well-being.”

Many students found that kind of creative camaraderie lacking during the pandemic, even when they were working together. Syed says she’s struggled to collaborate with her peers, and finds it harder to stay focused. “I felt like if [we had] actually [been] in the studio or the newsroom, maybe it would have been easier for us to work together,” she says. “People get distracted easily when they’re at home. To keep your focus, it’s very important that you share a space with your other classmates.”

But what she’s describing isn’t necessarily a problem that comes from physical distance, Scott says. It’s actually more about psychological distance. When a course, online or in-person, is designed well, it reduces the feeling of distance between students and their peers, their teacher, the content and the institution itself. “So, how do you create a sense of belonging to the institution? How [can students] feel connected to and seen by their teacher? Do they know who their peers are? Do they feel that their coursework reflects them?” This framework—Moore’s theory of transactional distance—was created in a distance learning context, but it has “massive, massive applicability in an in-person context as well,” Scott says. “Underpinning it all is creating community, a sense of belonging and an interest in study.”

Online courses at Athabasca have always incorporated activities that aren’t mediated by technology, and by extension, include movement and hands-on learning. “Online learning doesn’t mean that all learning happens in an online context. I think that, unhelpfully, the pandemic has given people that impression,” Scott says. “Everybody has the sense that online learning means sitting in front of your computer for however long, whereas actually, when you look at all of the courses that Athabasca offers, there can be project-based learning, and there can be hands-on, practical learning. We ship out rock samples to geology students. Students in the heritage resource management program do practicum placements in museums and galleries. Students who are doing masters of counselling work with patients. There are lots of activities that may go into an online learning course that are not mediated by technology at all.”

Hrach agrees. “Online education has typically been much more oriented toward asynchronous activities; only since the pandemic have we been relying so heavily on virtual meetings,” she says. “That may ease up as teachers figure out how to make better use of tools and resources.”

And even while lockdowns continue, or in the case of classes that are lecture-based, it’s possible to give students opportunities to move. Hrach suggests instituting movement breaks, which students of any age—or ability—can benefit from. “There’s a lot of variation in types of human mobility, assisted and unassisted, temporary and permanent,” she points out. “Activities should be designed with a variety of ways to participate. This semester, I began some of my virtual classes with chair yoga and breathing meditations. Students really seemed to appreciate these opportunities to pay attention to their bodies.”

Hrach also suggests sending students on a solo field trip, with instructions to report their findings to the class via a discussion board, whether photo, audio or video. Teachers can also assign podcasts, with explicit directions to listen while taking a walk.

For Syed, a podcasting assignment was a bright spot this past semester. Plus, she says, “our instructor would always have a little scavenger hunt for in-class assignments, which made us actually get out of the house and interact with other people from our neighbourhoods.” Breaking free of traditional methods like “posting the slides or the Zoom lecture,” she adds, “would be very useful, because it would intrigue a student’s mind.”

This article appears in print in the July 2021 issue of Maclean’s magazine with the headline, “Think on your feet.” Subscribe to the monthly print magazine here.