Fort McMurray fire: The great escape

Fort McMurray fire: The great escape

From the first puffs of smoke to the harrowing evacuation, this is the story of how the Fort McMurray fire happened, the heroic battle to fight back the flames and what it all means for the devastated city.

By Jason Markusoff, Nancy Macdonald and Charlie Gillis

Chapter One: ‘Puff of smoke’

Kim Fiske has a commanding view from two storeys up as she pilots a colossal, 400-ton mining truck, collecting payloads of shovelled bitumen destined for processing, pipelines and gas pumps. There’s an ever more majestic vista when she drives near the hilly edge of Suncor’s mine, looking south to the boreal forest that encircles the city she’s called home since 2010. It’s a city with a national reputation for its fast money and young roughnecks, but she tells friends back in Nova Scotia it’s a place where they can attend theatre every month, and where her poetry gets published in journals and on the walls of city bus shelters.

Near the end of her Sunday shift on May 1, around 4 p.m., Fiske noticed from her cockpit two little puffs of smoke in the blue-sky distance. “I said: have I lost my direction?” she recalls. “I thought I was looking at smoke stacks from one of the work sites. No, that’s toward town.” Fellow driver Sandy Horsnell, her husband, also saw them. He reckoned one was north of Fort McMurray (a fire that was contained quickly), and the other was near its southwest edge.

At 4:07 p.m., a fire patrol helicopter found that southwest smoke column. After bush fires near the city Saturday, wildfire crews were on alert. They discovered two hectares ablaze, around a small trail and power line corridor that often attracts recreational all-terrain vehicle riders. The chopper landed immediately, unloading a handful of highly trained ground workers. Within a half hour, an air tanker buzzed over to attack with water.

Within an hour, the sky began filling with black smoke. Fiske phoned her kids. “ ‘If anything goes to s–t, get in the car, take the pets, go,’ ” she told them. “Because it looked that bad. To me, it looked like the town was burning.” But the town remained safe, for a while at least.

By about 5 p.m. a second tanker joined the fight, along with what became a 12-person crew on the ground. But in the driest spring conditions Alberta has seen in decades, the spruce and poplar went up too fast—“extreme behaviour,” says Chad Morrison, senior manager with Alberta Wildfire. “Even with all those resources, it had grown to 60 hectares within the first two hours.” The temperature that afternoon peaked at 24° C, quite warm for early May. Inside a wildfire, it can eclipse 800°.

The wind and hot weather were like fork and knife for the wildfire’s ever-growing buffet. Danger edged eastward closer to Alberta’s fifth-largest city, and one of the Canadian economy’s most vital. Around 8 p.m., the municipality’s emergency department warned people in the Centennial trailer park in the city’s south to leave their homes, and put the adjacent neighbourhoods of Beacon Hill and Gregoire on alert. Around 10 p.m., Mayor Melissa Blake declared a state of local emergency and issued a mandatory evacuation order for at least 500 McMurrayites, and opened a refuge at Macdonald Island recreation complex downtown.

As the sun rose Monday, the 60-hectare burn area had grown to 750 hectares—or 7.5 sq. km—nearly double the size of Vancouver’s Stanley Park. Flames had gotten nearly one kilometre from Highway 63, the vital road through, around and out of the city. But firefighters who worked through the night were doing well enough that officials decided to downgrade some evacuation notices. Overnight, the fire expanded west, away from the city, and on Tuesday morning, air pressure kept the smoke and flames out of urban view.

Still, at an 11 a.m. media briefing that fateful day, Fire Chief Darby Allen warned that the winds and fortunes were prone to shift, and this was now a 2,600-hectare fire. “Don’t get into a false sense of security,” he said ominously. “We’re in for a rough day. And it will wake up, and it will come back.”

Allen was right, and what followed is one of the most terrifying spectacles in Canadian history—a phalanx of panicked drivers creeping through a downpour of flame, glowing embers and soot, second-guessing what they should have packed in their haste, or wishing they’d been warned in time to pack at all. “It was like something out of a movie, honest to God it was,” says Anthony Policicchio, who fled with his wife, three children and two dogs. “It was the scariest thing we’ve ever had to do.” Chris Byrne, a local radio personality, described it as “going through Mordor”—an allusion to the hellish domain in Lord of the Rings.

Flames rise in an industrial area (bottom) and along Highway 63. The past winter and spring were the driest in 72 years. (CBC/Reuters)

The inferno left thousands of residents with burned-out lots where their homes stood—where they had cooked suppers and watched reality TV and tucked their children into bed. While the firestorm’s path spared most homes and the city’s hospital, airport and other major infrastructure, all of Fort McMurray’s 88,000 residents became disaster refugees, sheltered in oil sands work camps, campus dorms, evacuation centres, friends’ homes or any safe harbour they could find. A schedule for re-entry will likely come in the third week after the exodus, Premier Rachel Notley announced May 9.

The wildfire, which by midweek had consumed 229,000 hectares of forest, would shutter oil sands operations worth millions of dollars a day—the latest toll inflicted upon a provincial economy already shattered by low oil prices, and a still-new NDP government coping with fiscal books drenched in red ink. Alberta now faces a multibillion-dollar recovery tab it will share with Ottawa and the insurance sector.

Yet the Great Fire of Fort McMurray would also feature a singular, miraculous fact: nobody died, or was injured, in that perilous mass escape. Two teenagers lost their lives one day later, as their SUV collided with a tractor-trailer some 200 km out of the danger zone. But the improbability of so many surviving is plain to anyone who has watched the harrowing smartphone clips of crowded vehicles running the canyon of flame along Highway 63.

Over the ensuing 10 days, those people—flung from their city until at least late May —would travel a giddy arc of emotions, from fear to gratitude to anxiety to grief to uncertainty to girding for a long haul. Two per cent of Alberta’s population was displaced in the largest prolonged evacuation in Canadian history. Yet the other 98 per cent eagerly embraced them with donations, clothing, free meals and countless other manifestations of kindness. The rest of Canada—and much of the world, including Pope Francis—joined in outpourings of sympathy and solidarity, having watched a mammoth emergency unfold live on social media.

If that came as surprise, it shouldn’t have. Long regarded as the boiler-room of Canada—or worse, an outpost for people seeking a quick buck—Fort McMurray has evolved beneath our noses into a surprisingly cosmopolitan place, with ties reaching all around the world. A few years ago, its leaders celebrated its diversity by raising the flags of every nationality represented among its citizens. They maxed out at 76, and last week’s media images reflected the new reality. Arabs, East Africans, Australians and Germans all counted among the evacuees. Residents wondered about the future of amenities few outsiders knew Fort Mac had, from its performing arts centre to a recreation facility that bills itself as the country’s largest.

Inevitably, questions have already arisen as to the whens and whys of the response—especially the haphazard progression of May 3’s evacuation orders. “Two days before, we were all told about the fire,” Cassandra Benson, an angry resident, told Maclean’s. “The evacuation should have been mandatory then, the day they knew the fire was coming. But they didn’t. They kept saying it’s voluntary, or it’s safe to go back home when clearly it was not.”

Wildfire officials, meanwhile, have been at pains to explain how a spot fire near the edge of town could so quickly escape their grasp, jumping highways and rivers to get to residential neighbourhoods. A season of unprecedented dryness converged with fell winds and a record spike in temperatures—conditions, they stress, that can transform a glowing ember into a zig-zagging blaze that constantly outflanks them.

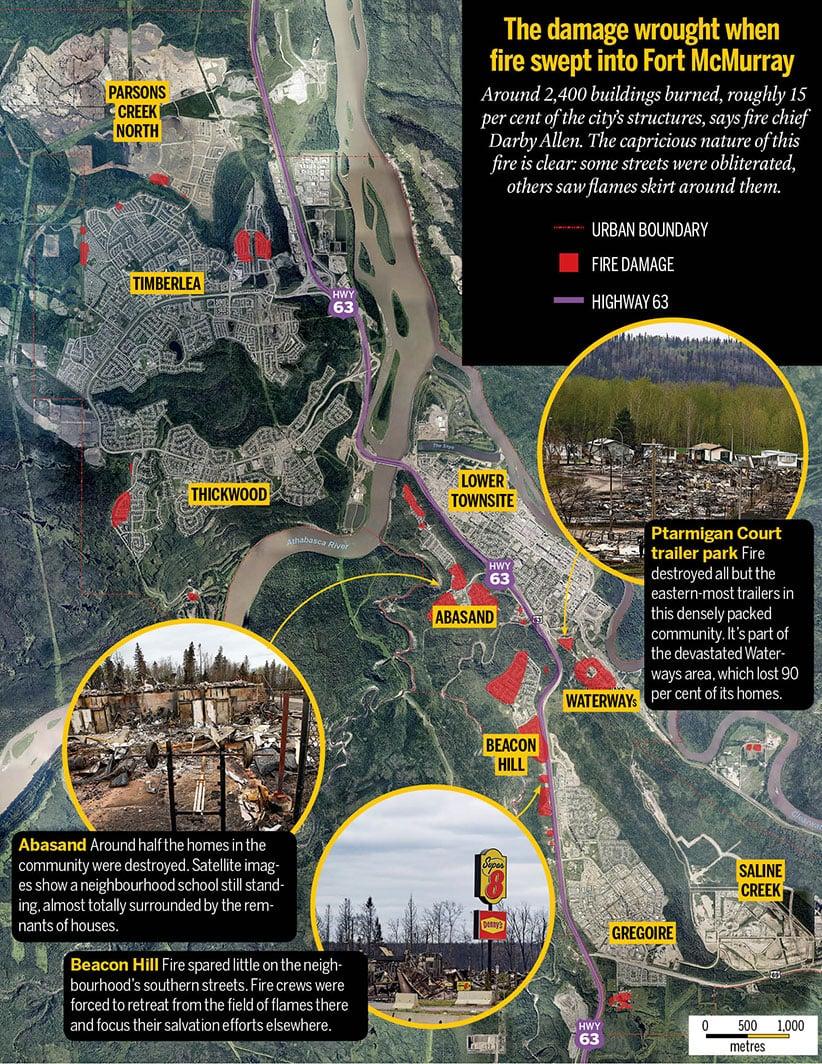

But the diligence of preparations, and the mechanics of the response, remain an afterthought next to the bravery and frantic effort that averted a much greater catastrophe. After viewing the wreckage up close on Monday, May 9, Notley announced that the blaze had wiped out 2,400 structures, 50 per cent more than initially thought. But she marveled at the battle that preserved 85 per cent of the city, repeated the mantra on the lips of most Fort McMurrayites looking back on their community from afar: “We will rebuild.” For thousands who rushed through the flames, that’s a bittersweet declaration. Those who intend to return face long days in evacuation facilities or strangers’ houses. Some will wait months to live again under their own roofs. But none of that can be worse than what they’ve just endured.

Chapter Two: ‘So dry’

Fires are part of the natural life cycle of any forest, a replenishing force we worry about inasmuch as it threatens people, buildings or timber for harvest. But in the boreal forests of northern Alberta, they occur on an epic scale, with a vengeance that suggests some malign force is behind them. This recent fire is the fourth in the Fort McMurray area to consume more than 100,000 hectares in the last 15 years. Unless it grows substantially, it will come in near the bottom of that ranking—paling next to the 2011 blaze that wiped out record 700,000 hectares, causing about $400 million in damage to Canadian National’s Horizon oil sands plant.

That blaze scorched an area larger than Prince Edward Island, and it started the same day as one that tore through Slave Lake, destroying one-third of the north-central Alberta town. Though much smaller, the 4,700-hectare Slave Lake fire looms large in the Alberta psyche, because it rode in on 100-km winds, crossing local fireguards so suddenly that residents could see their homes and cars going up in flames as they fled. Miraculously, all 7,000 escaped. You could forgive people for thinking that only an evil mind—or maybe an angry god—would devise such an instrument of destruction.

(Photo illustration by Lauren Cattermole and Richard Redditt)

The trouble starts, we know, with an uncommonly dry forest. The perfidious wind and igniting spark will inevitably come along—the latter, often as not, from a flying cigarette butt or a spark from an all-terrain vehicle (ATV). Herein lies the story of every major wildfire to strike the Fort McMurray region. Since the 1960s, per-decade average temperatures around the city for the seven-month period between October and April have risen a stunning 3.4° C. During the same period, Environment Canada records show, precipitation levels have plummeted from a total of 161 mm in the seven months between October and April to just 80, turning the densely forested area around the city into a giant tinder box.

Even by modern norms, this is a nightmare season for fire crews. The past winter and spring were the driest in the 72 years Fort McMurray has been gathering weather data, with 61 mm of rain and melted snow. It was also the second-warmest, culminating in a record spike in temperature on May 3 and 4, which pulled what little moisture there was from the forest floor. As Chad Morrison, the Alberta Wildfire senior manager, puts it: “This year, spring came three weeks early.”

Political leaders and companies in Fort McMurray have long understood the risk posed by this situation. Guy Boutilier, a former long-time mayor of the surrounding municipality of Wood Buffalo, who later represented the riding in the provincial legislature, recalls the colossal 1995 fire that engulfed Highway 63 about 120 km south, cutting off what was then the only paved route into the city. “After that, Syncrude and Suncor brought in bulldozers and plowed a huge fireguard around the city,” he remembers. “That was one of the lessons we learned back then. We know we are a city surrounded by forest.”

Boutilier and his council took other precautions, such as headquartering the city’s emergency operations centre in a bunker-like space within the municipal water treatment plant—a location that seemed safe from wildfires and other scourges. Since then, the city has kept up safety initiatives to clear away tinder-dry underbrush. Yet no such measures can obviate the essential risk faced by a bustling city pushing its way ever deeper into the surrounding spruce and poplar. The mere act of living in this place raises the chance of fire, notes Boutilier. Of that, there may be no better example than the inferno that started at 4 p.m. on May 1, 2016.

Experts, including Morrison, figure it was human-caused. The skies were clear that day, which all but rules out lightning as source, and while they may take weeks to pinpoint a cause, investigators trudging through the ashes this week have some likely scenarios. Coordinates released by Alberta Agriculture and Forestry, for starters, suggest the fire ignited near a small winding trail, less than 250 m from a corridor cleared to make way for high-voltage power transmission lines. These treeless avenues are magnets for hundreds of ATV enthusiasts—workers with enough disposable income to buy grown-up toys, and enough time off work to enjoy the gorgeous boreal back country. (From 2005-15, 63.7 per cent of forest fires in Alberta were caused by humans.)

Off-road groups and authorities frequently publicize the dangers of letting twigs or other debris gather in an ATV’s tail pipe, and urge riders to regularly stop and kick brush off the vehicle’s backside. It’s because of that risk that the Notley government declared a province-wide temporary ban on ATV riding on public lands days after the Fort McMurray fire.

Jim Wood, with wife Marilou, fills up his vehicle after fleeing Fort McMurray (Cole Burston/AFP/Getty Images)

ATV tailpipes, it goes without saying, are not the only potential human-related cause. Errant cigarette butts remain a constant hazard, despite endless warnings from wildfire authorities. And as unlikely as it sounds, the spark could have come from those high-voltage lines themselves—perhaps if a bird hit one and exploded, says Mike Nesbitt, a project consultant who helped install the lines in question 15 years ago. “The higher the voltage of the line, the bigger the explosion when wildlife makes contact,” he said. “That’s why I am not jumping to conclusions that a quad or cigarette started this fire.”

Whatever its source, the inferno that got going May 1 mocked the best-laid plans of city leaders. Fireguards were worthless in the face of a blaze travelling on 70-km/h winds, notes Morrison, adding: “This a fire that jumped a river that’s almost a mile wide.” Even that well-placed emergency operations centre came under threat, forced to relocate south to nearby Anzac—only to have to flee again when Anzac came under threat.

As such, the fire was bound to stir commentary about the climate-change elephant in Alberta’s room. On Tuesday, as the flames ripped into Fort McMurray, Tom Moffatt, a municipal employee in the southern Alberta town of Taber and a former NDP candidate, tweeted: “Karmic #climatechange fire burns Canadian oil sands city.”

At such a time of crisis, in a province so dependent on fossil fuels, the reaction was more than Moffatt bargained for. Anger poured in on social media, while practically everyone associated with him—even the library whose board he sits on—disavowed the remark. Moffatt hastily took down the tweet, apologized and grovelled his way through media interviews. But on Friday, Taber’s town council voted to suspend him from work, pending an investigation. “A recent post made by a town employee on a personal account in no way reflects the town’s views on this terrible tragedy,” the council said in a statement. “The town of Taber apologizes unreservedly.”

Overreaction, you might say. But it was an early sign of a sentiment that would define this crisis. With thousands left homeless by the fire, Albertans were in no mood for polemics or finger-pointing—and certainly not for a scold. What mattered most was helping the 88,000 people whose daily lives just a few days earlier reflected their own, shuttling from work to school and community activities, wholly unprepared for the terror to come.

A firefighting aircraft flies over Abasand, when the fire was just starting (Serghei Cebotari)

Chapter Three: ‘Worst-case scenario’

For a city facing the sharp edge of the oil economy’s crash, Fort Mac seemed to be still welcoming a steady flow of newcomers. Brian Schaefer’s marketing job moved him and his family from Minnesota in mid-April. By Tuesday, May 3, some of the family’s boxes were still unpacked.

Jerwin Magtibay, a migrant worker from the Philippines, was on day two of his job at a downtown Wendy’s after a year south in Medicine Hat.

And at 9 a.m., Kate Cox landed here for the first time.

Cox, 21, didn’t have a job yet, but was keen to leave Australia for this fascinating Canadian boomtown her friends told her about and in which she hoped to find work. It took five flight legs, two long airport delays and 53 hours to reach Fort McMurray from Scottsdale, Tasmania. Her travel companion had read about the wildfires during their Los Angeles layover. “When we landed, it was pretty smoky but it was still pretty all right,” Cox says. After dropping her bag off at a friend’s—she didn’t unload it—she set about starting her new life: cellphone number and bank account; instructions on getting an Alberta driver’s licence.

Meanwhile, blocks away at the government building, Regional Municipality of Wood Buffalo Mayor Melissa Blake started the 11 a.m. news conference by pointing out the irony that it was World Asthma Day, and she apologized that waste trucks could only pick up residents’ garbage and not their recycling bins; the fire had closed the city’s southeast landfill.

Allen, the fire chief, hadn’t yet begun calling the blaze “the Beast,” but was starting to anthropomorphize it, talking about how it will wake up and come back over the next few days. Despite that foreboding note, he added that it’s good how people are taking kids to the park, going about their daily lives. “Just keep in the back of your mind we’re still in this serious situation.” Forestry manager Bernie Schmitte explained that 70 firefighters were working the fire’s eastern front, still near the city. With a pause, he added that 10 more were attacking on a new front: a five-hectare “spot fire” on the other side of the Athabasca River. It’s an alarmingly wide channel for flames to hop, but at least in this case it was fairly far from the city.

The day’s forecast had the makings of trouble. Temperatures headed past 30°, setting a record. Heavy winds. Then there was the inversion, a term and common weather condition that henceforth will make McMurrayites shudder. Warm air had formed a kind of crust above Tuesday’s cool morning air nearer to the ground, holding down the smoke. As the day warmed, the inversion would lift—and wind could bellow the flames and smoke much higher. That would happen around noon, the officials said. “I don’t really want to talk about worst-case scenario, but the fire conditions are extreme,” Allen responded to a reporter’s question.

Even in neighbourhoods near the fire line, it took a subtle eye to spot the first signs of danger. Paul Mache, a plant maintenance supervisor who works in an industrial park at the southern tip of the city, noticed around noon that the formerly innocuous-looking smoke was now cutting through the sky at a 45-degree angle. “The wind was picking up and instead of it being a nice white smoke, it became black,” he says. “It started coming toward us.”

Mache was watchful, but it never occurred to him that catastrophe loomed. He’d been catching updates on the local radio station, Rock 97.9 (which is owned by Rogers, which also owns Maclean’s), and they didn’t sound panicked. He had friends in the Gregoire area who’d left their homes late Sunday, following an evacuation order the municipality later rescinded. This might be another false alarm.

That humble radio station would soon show its value, transforming from a conduit of Guns N’ Roses mainstays to a piece of critical communications infrastructure. Unbeknownst to most of the city, the southwest wind was now gusting to 70 km/h, while the temperature inversion had lifted, allowing the flames to rise toward their terrifying 30-m height. As Schmitte had suggested, wind-blown embers blew across the kilometre-wide Athabasca River, seeding the blaze on the northwest side of town. At noon, Chris Byrne, the station’s afternoon host, got a text from his program director, who’d heard that residents of Beacon Hill might soon be under another evacuation order.

The notice that came at 1:55 p.m. called for voluntary evacuation—residents of Beacon Hill, Abasand and some areas of the Thickwood neighbourhood, near where the fire jumped the river, were advised to leave. Rock 97.9 quickly took the message to air. Less than 15 minutes later, just as Byrne arrived early at the downtown station for his shift, the order was made mandatory, and that, he says, “is when the hair starts standing on the back of my neck.” He began calling relatives, advising them to get out regardless of whether they’d been advised to do so.

Cox and her Aussie friend, taking a break from her newcomer errands, went out for a late lunch. Exhausted, they went across downtown for a nap they cut short after 20 minutes, realizing they should be on the move—it was the only rest she would get in the 6½ hours she spent in Fort McMurray.

Horsnell and Fiske, the Suncor heavy truck drivers, were themselves napping at 2:30 p.m., ahead of their night shift. Their 23-year-old son, Ruben Rotar, a professional pianist living downtown, came to Timberlea to wake them up after seeing the gathering haze. The couple packed some extra clothes—Fiske thought she was being excessive by tossing moisturizer into her bag—and expected they’d still have to go to work, maybe stay overnight until danger passed. “We still took our lunches and stuff. We didn’t know the reality until we left about an hour later.”

At 3 p.m., Byrne hit the airwaves, spending much of the next hour repeating the names of the neighbourhoods under evacuation orders. From time to time, he would glance out a window. On the ridge above town, he could see a wall of smoke, interspersed with flashes of orange. The fire was headed toward the heart of his city.

Chapter Four: ‘Abandoning ship’

The only hint something might be amiss on Tuesday morning was the birds, which are known to be sensitive to changes in air pressure. They had been screaming and squawking something fierce, says Sarah Davies. “They were in a frenzy, flying in circles. They didn’t seem to know where to go.” In hindsight, to those McMurrayites who noticed them, anyway, they were an early warning that something was seriously wrong.

But in parts of the city, it took some time for panic to set in, even after the evacuation notices began going out. Esthetician Crystal Montroy, 28, remembers a client at Timberlea’s Achieve Wellness Spa running out after receiving a panicked call from her husband. Staff had a bit of a chuckle, thinking she was being overly dramatic. Montroy, who lost her home and everything in it, strolled out to her car to prepare to evacuate, initially unaware of the gravity of the situation.

Birds fly past billows of smoke. As the fire grew, air pressure changes alerted the birds to the danger. (Mark Blinch/Reuters)

Andrew Donnelly, who also lost his Timberlea home, saw men taking the time to douse their houses using hoses. As he and his five closest friends were preparing to leave Fort McMurray, they ran into an Eagle Ridge resident they’d never met before who invited them in to dinner. He’d cooked up an onion and mushroom meat hash. The music was pumping, and he offered them beers and a shower before they hit the road. “If this is going to be the last meal I cook, it’s going to be a good one,” his new pal said. By all accounts, it was. They pulled out of Fort McMurray together, in a five-car convoy.

For many, terror finally set in when the fires became visible. At the downtown Shoppers Drug Mart, sales associate Zsa Zsa Pardales Lalisan-Torio’s heart dropped when her co-worker pointed to the store’s window, where smoke and flames were creeping over the ridge. She phoned a friend, asking her to pick up her daughters from school. Seconds later, she heard an evacuation order go out. At that point, Lalisan-Torio grabbed her purse and left. As she was walking out, an alert went out over the loudspeaker, telling shoppers and staff to exit immediately. That’s how quickly the situation turned.

At that point, still before the mandatory evacuation order, Courtney Peddle, 19, was home alone in Abasand when her mom called: “Don’t panic,” she said. “But I want you to pack a bag, in case we need to leave.” Within minutes, smoke was flooding their home. “I was terrified—I didn’t want to leave Gus,” her grey cat. Soon, the power started to flicker: “The lights were going in and out.”

Suddenly, the evacuation orders were coming fast and furious. Back at the radio station, Byrne relayed a notice at 2:25 p.m. that Thickwood was under a voluntary notice. By 3:10 p.m. it and a neighbourhood called Wood Buffalo were under a mandatory order, and over the next 20 minutes, compulsory orders came in for residents to leave Dickinsfield, Saline Creek and Waterways. Just before 4 p.m., the entire downtown area was added to the list. Reluctantly, Byrne set up a computer to run the station automatically, and retreated with his engineer to the RCMP station in Timberlea, which had not yet been evacuated.

There, they got a remote broadcast up and running for another 45 minutes. But at 6:20 p.m., they were told to shut down and get out. “It felt like abandoning ship,” says Byrne, noting that with cellular networks overloading, thousands were tuning in for life-and-death information. “To not be able to do that because you’re part of the news story is not a fun feeling.” Once again, they left the station on autopilot, with a recording that played after every second song. “The city of Fort McMurray is under a mandatory evacuation notice due to wildfires,” said the message, written and recorded by program director John Knox. “If you are north of downtown, please proceed north on 63. If you are south of Beacon Hill go south to Anzac. Do not call this radio station. It is unmanned.”

Inside schools, panic set in as news of the evacuation orders spread. At École McTavish Junior High School, 14-year-old Hyeqa Ahmad was locked into her classroom on the orders of the fire deparment. “By that time, kids were getting texts and calls from parents. Some were crying, and panicking,” says the whip-smart Grade 9 student. “It’s scary—your family is trying to evacuate, but you’re stuck at school.”

To be let out, each student had to be signed out by a parent. When the older brother of a close friend of Ahmad’s came to pick her up, he was denied: Her friend had to stay until a parent could reach her, which took hours.

The suddenness of the evacuation order meant that some of the families initially evacuated Sunday had already returned home when the municipality’s frantic, rapid-fire round of orders starting going out neighbourhood by neighbourhood Tuesday afternoon.

That’s what happened to Cassandra Benson, 20, a student. Sunday night, she and her 18-year-old brother, Tyler, their mom, Shirley, a waitress at O.J.’s Steak and Pizza in Gregoire, and dad, Trevor, a driver for Green Transport, were evacuated to MacDonald Island Park, the downtown rec centre at the fork of the Athabasca and Clearwater rivers. The family spent Sunday night in the parking lot, in the cab of Trevor’s five-tonne truck with their 10-year-old tabby and two dogs, Milo, a purebred Rottweiler, and Cali, a Huskie cross. But on Monday at 5:46 p.m., the order was lifted, and the Benson family headed home to the Golden Eagle Trailer Park, believing the emergency was behind them.

Some time after noon on Tuesday, Cassandra and Shirley headed downtown to pick up food for Milo and Cali. At 1:55 p.m., as they returned home, they started hearing the evac notices come in over the radio.

By the time they got to the city’s south end, the evac orders were moot: “It was just flames everywhere,” Cassandra recalls. “Abasand was on fire. Beacon Hill was on fire. Cars came flying over the hill. Animals were running ahead of the flames. Some people were stopping, to scoop up dogs and load them into their cars.”

For a few moments Cassandra and her mom were too stunned to move: “I turned to the left, and watched every single streetlight at Gregoire Lake Estates explode,” says Cassandra. “Power lines were exploding, the wires ripping right out of their sockets, and breaking off the poles. It felt like World War III.” When suddenly the fire leapt the highway they were jolted into action, and bolted to Shirley’s truck.

Passing a Gregoire McDonald’s, Shirley saw a small fire starting outside the restaurant, and they stopped to try to stamp it out. When they got back in the truck, Cassandra called her dad, who was with Tyler. “Go north!” Trevor shouted. “Just drive! I’m going to get the dogs and the cat.”

By then, Shirley—terrified by the fear she could hear in her husband’s voice, the squawking, automated evacuation orders playing in a loop over the radio, and the out-of-control fires—was panicking. Because she has heart problems, Cassandra was trying to calm her. “I was squeezing her arm, and holding her hand. I made her breathe in through her nose, and out her mouth. I kept telling her we were going to be fine, that we were going to make it out.”

To the north of the city, the sudden lurch from blue to black skies was no less dramatic. Heather Gallant was having lunch at Paddy McSwiggins, a popular Irish pub downtown: “We could see a little smoke when we sat down,” says the P.E.I. native. Then all of a sudden, midway through lunch, “I looked over, and there were six fires. Pieces of pine needles were floating into our food.” Everyone got up and bolted for the parking lot all at once, she says.

“On our way home, we heard a great, big squeal over the radio station: The evacuation notice.” When she got home, she ran to wake her husband, who was sleeping off a night shift. “Come on now, Heather!” he said. “Calm right down.”

“Look yourself, out that bedroom window,” Gallant shouted, ripping open the blinds. His jaw dropped to the floor. “The whole sky was just red.”

Tuesday was an off-day for Anthony Policicchio, who works as director of operations for a site services company in the oil sands. That afternoon, he and his wife, Joan, had driven 15 minutes northwest of their Timberlea home, to a three-hectare plot of land where they keep the family’s horses, Prince and Flare. “We could see the flames coming in,” he says. “The horses got spooked. We tried to arrange trailers to get them out, but we couldn’t get the trailers in. So we had to just open the gates, let the horses go, and hope for the best.”

As the clock approached 3 p.m., the Policicchios sped back toward the city, picked up their three kids from school, and headed toward Highway 63. They had no time to pack, bringing only the clothes on their backs and their two dogs. “I know the news was telling everybody to go north, but I didn’t want to go north because once you get north, if the fire goes that way, there is nowhere else to go,” Policicchio says. “So we made our way south.”

The road was surrounded by flames, the smoke so thick and black he could barely see past the windshield. “I was just terrified,” he says. “I was worried about getting my family out safely, and the whole time you know it’s not a good situation and you’re wondering if you’re doing the right thing or not.”

Cars fill the highway as people leave the city following a mandatory evacuation order (Jason Franson/CP)

Chapter Five: The ‘mile of hell’

“Just don’t look up,” Sarah Davies was told by a friend before making a break from her home in Waterways, Fort McMurray’s original settlement. “I didn’t even have shoes on. I just looked at the ground, and ran. You could feel the heat, the rush of the fire—it sounded like a really strong wind. When I did look up, I froze. All I could see was flames. I couldn’t breathe.”

Davies and her husband, Scott Abercrombie, made it to their truck, then drove a few blocks before stopping to watch the fire claim their neighbourhood of three years—Davies, still in her socks, with tears of disbelief slowly soaking her blue T-shirt.

“The first thing that crosses your mind is that everything you owned, everything you worked so hard for is gone,” says Abercrombie, a great bear of a man, choking back tears.

Stephanie Pickett was trying to escape downtown Fort McMurray on Tuesday afternoon with her two sons, Alan, 8, and Andre, 11, when her eldest suddenly screamed: “Mom! Flames!”

The raging fire was chewing its way down to the hospital and toward Pickett and her boys, who were stuck in bumper-to-bumper traffic. They waited a few moments before the native of Indian Bay, N.L., made the call: “Run!” They abandoned the car, and ran from the approaching flames, Pickett pounding the pavement in her flip-flops.

Her fiancé, Chad Kean, her partner of 17 years, was meanwhile trapped in traffic on Abasand Hill to the south, watching the fire close in on him from his rearview mirror. “That was the scariest moment for me,” says Pickett: “Racing with my kids, not knowing whether he was going to make it out or not.”

Scott Abercrombie and Sarah Davies saw the flames claim their neighbourhood (Photograph by Amber Bracken)

She and the kids jumped into a second truck being driven by her cousin, then fled north, running out of gas outside Fort McMurray. They spent the night beneath the aptly named “Bridge to Nowhere.” Kean, also a Newfoundland transplant, was forced to go south.

In Beacon Hill, meanwhile, Christina Nicholson was lounging in her pyjamas on a day off from her scaffolding job when a housemate warned her of the approaching flames. She couldn’t get her terrified cats out of the furnace room in time, but grabbed Cinder, her black chihuahua. By then, flames were already devouring the neighbourhood, turning it into a fiery hells cape.

Blocked in by traffic, Nicholson ditched her car, and sprinted to her mom’s Jeep that was ahead of her in traffic, taking over the driver’s seat. She roared up onto the sidewalk, turning away from the wall of flame at Beacon Hill’s exit, then down a 4.5-m grassy bank and up a ditch to Highway 63.

In Timberlea, in the city’s north end, Erica Frantze had a panic attack as she hit a wall of traffic trying to leave her neighbourhood. The mother of two, who runs a daycare from her home but happened to be taking a week off, handed the wheel over to her dad, who was in the car with her. “I knew in my guts we should have left hours earlier. I was so scared for my children: Was the fire going to get us while we were sitting there? Would we burn to death?”

She and her dad hatched a hurried plan to cover her children, two years old and seven months, in blankets and lie in a nearby culvert if the flames came any closer. “We didn’t know if we were going to make it out.”

To the south, the developing scene was apocalyptic. “In Beacon Hill, there were houses exploding, cars exploding, propane tanks exploding,” says Nicci De Leeuw, who works for SGS, a local oil and gas firm. “We had chunks of insulation raining down on the truck. Kids were passing us on horseback, running their horses through flames. The air was thick with black smoke. There are no horror movies as bad as that.”

As Nicholson rolled past the flaming trailers of Centennial Park on Highway 63, “it was pure black except for big chunks of red. I was worried the tires would catch fire, or the air bags, it was so hot,” she said. Her car’s interior temperature clocked in at 50° C, as she pushed south toward safety.

Despite the panic, the exit was remarkably orderly, with drivers, for the most part, yielding to allow others in and obeying traffic laws.

But getting out of Fort McMurray proved to be only half the battle. Southbound drivers next had to pass through the “mile of hell,” a 20-minute southbound stretch of Highway 63 that took drivers through a wall of fire on two sides.

Winnie Lachica, a bus driver with Wood Buffalo Transit Authority, and his family, was among the first allowed through it, on Tuesday evening.

The RCMP, until that point, had been routing all traffic north, but the two-lane highway got so jammed up, it was turning into a parking lot. “I was scared the city was going to burn out, and everybody dies,” says Lachica, a native of the Philippines. At that point, he says police opened the southbound lane, to allow drivers through the flames. But the new route gave Lachica pause, and he pulled off the highway to quickly consider the new approach.

At 42, he is the family’s senior-most member in Canada, the person they trust for advice on life’s big questions. On that day, Lachica was leading a convoy of five carloads of family members trying to escape Fort McMurray. He was driving a car with his wife and kids.

“It’s my entire family, and they are relying on me. If we go forward, and even one car blows up from the heat, we would all die there: There is no way out. We would be trapped.” But as he sat there, quietly deliberating their fate, Lachica, a deeply religious man, saw his friend’s house catch fire from his rearview mirror. His resolve suddenly hardened: We need to get out of this town, he thought. Jesus will be with us.

He began quietly crying as he pulled out, praying the decision was the correct one, the flames licking at his car. He could barely see through the black smoke. It grew so hot inside, his wife began dousing their kids’ heads with water, to cool them, and clear their eyes and noses of smoke.

In a car somewhere not far behind them, Rhoda Keating, a hospital records technician was praying aloud: “Please Jesus, save us.”

“Keep coming south, Mom,” her daughter would periodically call to say, to encourage her mom, who was travelling solo. “The car was getting so hot,” Keating recalls, hotter even than when the Beacon Hill gas station blew up next to her. “I was so frightened. I thought the car might explode from the heat.”

Small wonder then, everyone remembers the jarring calm immediately following the flames. “Ahead, there was nothing but clear, blue sky,” recalls Eagle Ridge resident Brandy Brake, 38, who was in her first day back to work as a receptionist at Max Dental after an extended maternity leave. “You would not think anything was wrong. It was like heaven and hell. If you turned to look behind, it was nothing but black—like Fort McMurray was being swallowed up.” Brake cried the entire drive out of town, terrified for her 14-month-old boy, who has breathing problems, and had been struggling throughout the day.

Weary Fort Mac residents get some rest at the Bold Centre in Lac La Biche, top; Evacuees arrive at a temporary shelter at Edmonton’s Expo Centre at Northlands (Photographs by Chris Bolin and Amber Bracken)

Along the road, they kept passing cars that had been abandoned as they ran out of gas. Glen Parsons, 54, left a note on his windscreen before walking away from his truck in Grasslands, 260 km south of Fort McMurray: “This is my last possession in this world. Please don’t tow it away, or impound it.”

De Leeuw didn’t break down until she pulled to a stop at a roadblock in Wandering River, a whistle stop south of Fort McMurray. Her truck was running on fumes when a police officer reached in the window to hold her hand. “You just tell us what you need,” the officer said, gripping her palm in his. “What can we do for you?” “I just need quiet—10 minutes to get myself together,” she said, through tears. “So he sent us to this little spot down the road where we could let the dogs out and just rest. Volunteers came and filled up our truck with gas, and brought coffee.”

It had only been a few hours since the mass exodus began, but the massive humanitarian effort was already under way, with shelters sprouting in Anzac, Lac La Biche, Athabasca, Edmonton. The local chapter of the Ahmadiyya Muslim organization dispatched members north, carrying gas. Other citizens, their flatbeds loaded with jerry cans for stranded Fort McMurrayites, were doing the same. “That $10 worth of gas they brought literally saved me,” says Andrew Donnelly, 30. “I would have been stranded without them.”

Yet many evacuees, including De Leeuw, who was travelling with her 24-year-old son and their three German shepherds, were still not safe. De Leeuw put up their tent trailer at a boat launch outside Anzac on Gregoire Lake, to let the dogs stretch their legs. At 11:30 Wednesday night, after lying down to try to catch a few hours rest, she was awoken to a text message on her dying cellphone, which had dimmed to preserve battery power.

“Anzac evacuated one hour ago,” it read. Am I reading that right? De Leeuw thought to herself. Since she’d forgotten her glasses on the kitchen table back home, she stepped outside the trailer to plug the dying phone into her truck to get a clearer view of the message. But as soon as she stepped into the night, her black cell suddenly turned bright orange, reflecting flames: The raging fire had caught up to them in Anzac. It was less than 100 m from their lakeside campsite, set to swallow them whole.

“It’s right there—it’s right there,” De Leeuw screamed at her son, waking him. “Get out! We gotta get out!”

They abandoned the trailer, careening down Anzac’s gravel access roads, doing upwards of 100 km/h in their pickup truck to escape the flames, her son tracking their progress through the back window. Days later, De Leeuw’s body is still trembling. “I can’t stop—I’ve been shaking since Tuesday,” she says.

Chapter Six: ‘This province is incredible’

For more than 20,000 Fort McMurray residents who fled north, either because it was the closest exit or because Highway 63 south was closed, the immediate danger was behind them. But they were still at risk, surrounded by dense forest that threatened to burst into flame with a simple shift in the wind. “There’s nowhere to go if the fire headed for us,” says Heather Gallant. “It doesn’t matter how far you run. There’s nothing but trees all around us. There’s nowhere to flee.”

Fortunately for Gallant and thousands of others, the wilderness north of Fort McMurray is also home to nearly a dozen massive oil sands operations—some effectively small cities—and their sprawling work camps. By some counts the camps are capable of housing a “shadow” population of as many as 43,000 workers.

Gallant headed for Shell Canada’s Albian mining camp, 70 km north of Fort McMurray. We gotta get out of here, she kept thinking. Everyone else there thought the same thing. Within hours, Shell, which housed 2,000 evacuees at Albian, began a massive, coordinated evacuation, running 8,000 more to Edmonton on flights from its Albian airport over the next four days on airlines including WestJet and Canadian North.

Other oil sands firms experienced a similar rush of evacuees. Suncor Energy sheltered about 2,000 people and helped fly out 6,800 over a period of four days, a spokesperson said. The effort was made possible by about 40 Suncor employees who volunteered to help provide food and water to evacuees, as well as load and unload aircraft.

Syncrude Canada’s Mildred Lake site hosted another 2,000 displaced people, mostly workers and their families, who showed up with dogs and cats in tow. “I believe one of our senior managers even built a cat box,” recalls Will Gibson, a Syncrude spokesperson, who was forced to flee from Fort McMurray along with everyone else. “Everyone pulled together to make sure people were looked after because that’s what it was all about.”

A few made a dash for it on their own, by car. “My wife is eight months pregnant—there was no way we were staying up north,” says Scott Ruth, a Suncor employee. Ruth was able to monitor Suncor’s traffic cameras, and as soon as he saw an opening, early Wednesday morning, he and his family made a run for it. Maclean’s met them inside Edmonton’s Northlands Expo Centre, the main evacuee staging area in the city’s northeast, shortly after they’d received word their house in Timberlea was likely among those lost. Kelly Holden wore sunglasses to try to shield her tears from their two kids, Owen, 7, and Naomi, 5. “We’re just trying to keep strong for the kids so they won’t be freaked out,” says Ruth. “It’s an emotional rollercoaster.”

Indeed, many of the evacuees who streamed into Shell’s private terminal at the Edmonton International Airport broke down upon clearing the gate, their relief at making it out of the north bittersweet. “That’s when it finally hits: ‘I’m safe. But I’m still not home,’ ” says Gallant. “I can’t just walk down the street and go home. Where do I go from here?”

Sabrina Leung Powers and Kristy Golightly (right) of Beaumont, near the Edmonton airport, gathered supplies from neighbours for evacuees (Halsi Sears)

For many, the tiny town of Beaumont, Alta., located just north of the Edmonton International Airport, was there to help. It devoted itself to assisting the evacuees flying in from the north. It all started when Kristy Golightly, 36, noticed evacuees, many still reeking of smoke, filling buses headed to Northlands Expo Centre. “They had nothing,” says the 36-year-old travel agent. So Golightly and Sabrina Leung Powers, who owns Beaumont’s Kryptanite Tanning Salon, turned to the community. Wednesday night, Powers put a call out asking for supplies. By the time she got to Kryptanite the next morning, there were food and supplies piled up outside her door, and people lining up to help.

For days, Beaumont, with a population of just over 13,000, supplied the evacuees with everything from new strollers and car seats to underwear and clothes. Cosmic Pizza cooked so many pies that owner Sheraz Aziz ran out of supplies, and had to close his business to restock. When one woman mentioned her cat had a thyroid condition, a Beaumont vet took it in. And when the Grande Cache Home Hardware heard a boy had raised $215 selling popcorn and lemonade to try to buy bikes for two Fort McMurray boys, they gave the boys brand new bikes and helmets.

On Saturday, when a four-year-old boy headed to the Beaumont Community Church to donate his two favourite stuffed animals, a two-year-old girl from Fort McMurray took him up on the offer. Her mom was moved to tears. The family lost their home in the fire. But the outpouring of support and help from Beaumont—and, indeed, from every corner of Alberta—is helping them through the tragedy.

Nicci De Leeuw turned up at the airport to pick up her husband. (He had evacuated north out of Fort McMurray, while she had been forced to drive south to escape the fire.) She asked an airport mechanic to recommend a local repair shop to fix the squealing brakes on her truck. Instead, he redid the truck’s entire braking system for her, a job worth several thousand dollars. “The friendliness of this province—it’s incredible,” says her husband Shane Willett, a native of Ignace, Ont., choking back tears.

Back up north, it wasn’t just the oil sands companies pitching in. Fort McKay First Nation opened its band hall, arena and school to about 3,000 evacuees. Fort McMurray First Nation, just southeast of the city, had became a key refuge early on before approaching fire forced its evacuation as well. And Fort Chipewyan, accessible only by air, flew down some of its firefighters to help, as a small flotilla of boats from the south brought some locals back up to Fort Chip.

Soon enough, however, many of those who had provided shelter were forced to take refuge themselves. As the weekend approached, and with the inferno growing ever larger, several oil sands firms abruptly abandoned earlier plans to merely scale back production and decided to shut down operations and evacuate their own staff. For Syncrude, it was the first time in nearly a half-century its entire operation was taken offline. The last Syncrude worker touched down in Edmonton at 1 a.m. Sunday, leaving behind only a herd of wood bison that roam a parcel of reclaimed land as part of a sustainability project.

In addition to its base plant, Suncor decided to shut down its MacKay River and Firebag operations. It was also forced to make a mad dash to improve its fire defences around the perimeter of all three properties—namely bulldozing flammable timber and vegetation. Others that shut operations because of the threat of fire, smoke or pipeline closures that squeezed off the supply of diluent (needed to keep the viscous bitumen flowing) included Husky Energy, ConocoPhillips and Shell. Amazingly, the only oil sands producer to have suffered any direct damage from the flames, albeit minor, was China-owned Nexen Inc.

Chapter Seven: ‘Ghoulishly quiet’

Near the front of an incredibly long lineup of trucks and cars, a Mountie tapped on Bill Glynn’s window after 5 a.m. Friday.

The convoy was about to begin. If the cop hadn’t awoken Glynn, celebratory honking would have.

With the fire threatening to spread north, and supplies dwindling for 25,000 evacuees and stranded workers, airlifts weren’t going to get them all out. Once the threat that Highway 63 would burn again had subsided, the RCMP would escort motorists stranded north of Fort McMurray through the fire-scarred city and south toward Edmonton. Provincial officials had hoped to begin letting thousands of vehicles roll Thursday, but the road remained unsafe. Glynn, a Syncrude worker, got there early Thursday morning and, unlike many other marooned workers or families, he chose not to leave the lineup. He’d not return to the Athabasca work camp. This oil sands commuter would commute home to Edmonton as soon as possible, and for his patience he was second among the thousands waiting to drive south onto freedom, via a massively charred city, soupy with smoke. “Just like a bombing area. Couldn’t see a hand ahead of you—God, she’s rough,” he told Maclean’s at a diner three hours south in Lac La Biche, eggs and bacon his first hot meal in 24 hours.

Devon Bourdeau and four friends joined the convoy Friday morning, then stopped at the first gas station south of Fort McMurray to grab a bag of ice to chill a bottle of Veuve Cliquot, and grab paper cups as champagne flutes. Before he escaped north on Tuesday, Bourdeau hopped a couple of curbs to reach a city liquor store, and spent $350 on liquid provisions. Three days later, they popped a cork and celebrated.

Grief mixed with revelry among Bourdeau’s crew. Ali Russell’s landlord had sent pictures the night before of her destroyed home in Beacon Hill, from which she could retrieve nothing but Brooklyn, her German shepherd. Jessica Stuckey’s security company revealed her house in Timberlea’s Prospect district was lost. “The worst part of it is when you’re sitting by yourself and you realize your house is now gone. Even if you prepared yourself for it, with a little bit of hope maybe your house would be standing,” she said. Facebook images of flames roaring on Prospect Drive helped prepare Stuckey for the worst.

The convoy route stayed on Highway 63 through Fort Mac. Police cruisers blocked off entrances to the neighbourhood.

Maclean’s gained access to the city Friday with a guide authorized to be in the city, and was able to do what Stuckey was forbidden to: turn onto Prospect Drive and see what the fire took and what nature and firefighters managed to spare. She’d have first seen the shopping plaza that opened just two years ago. The Save On Foods, Canadian Brew House, and its not one but two liquor stores— all untouched by disaster, the complex’s walls black and grey by design.

Residents heading back south on Highway 63 drove through the ruins left

by the fire, like burned-out cars in Timberlea (top) and charred patio furniture (Photograph by Chris Bolin; Scott Olson/CP)

A few metres away on Sandstone Lane, fire had chewed through the back half of a corner house. Beyond that property’s backyard was another grimmer vista of black and grey: charred cars and dead homes. A “For sale” sign was tattered and curled by intense heat as smoke wisps rose slowly from the charred ruins behind it. The shell of a car was lifted onto its side, perhaps by one of the bulldozers that appeared to come in after the flames destroyed entire blocks. Large, fresh tire treads were carved into many yards and overtop foundations, creating a huge mess of earth and rubble.

The decorative stone edges around a series of house garages remained, in whole or part, now like broken and empty picture frames, some with melted remains of garage doors hung up by guide rails.

There were few visible vestiges of the family belongings left behind. In one backyard, a trampoline was still there to jump on, and a few doors down a red kiddie Corvette was upside down, but appeared otherwise fine.

In some areas it was hard to tell easily what the winds and flame patterns spared, and what first responders had helped secure. Around the edges of this charred neighbourhood some homes merely had warped vinyl siding, and on the balconies of a brand-new apartment complex sat camping chairs and barbecues.

That half-gone house on Sandstone Lane is more likely a signal of firefighting—flames don’t just get bored and quit halfway through a house. The municipality announced it was able to protect properties on the other side of Confederation Way, a key artery that loops around the communities of Timberlea and Thickwood, both largely intact and which together hold about two-thirds of Fort McMurray’s population. After Wednesday night, the city suffered no major fire damage, as the flames spread east toward Saskatchewan.

The province and municipality co-hosted a tightly controlled media tour on Monday. Allen, the fire chief, told reporters that 15 per cent of the city was destroyed—it could have been between 40 and 50 per cent without firefighter efforts.

In those intact neighbourhoods, it was ghoulishly quiet and otherwise ordinary. Blocks from Prospect’s carnage, houses still had their black garbage and blue recycling bins lined up outside for collection day. The water treatment plant was fine, as was the hospital and all the city’s core. A drive up Franklin Avenue, downtown’s main drag, was the same as it ever was, except for an inflatable tube man atop one building that now drooped down from the roof.

It’s inaccurate to say Fort McMurray was completely evacuated. RCMP officers went door to door for days seeking stragglers. They pulled out a willing few, but could not compel stubborn ones to leave, including a couple with three young children who insisted Thursday they weren’t in danger.

Roy Powell shrugged off the mandatory evacuation and neighbours’ pleas, and was reluctant to leave when two officers found him in his Timberlea mobile home on Wednesday, 18 hours after everyone was ordered out. “Because I live by myself, I can be stubborn like that,” the 69-year-old told Maclean’s, after relenting and being bused to Lac La Biche.

John Howe didn’t want to be stranded Tuesday night and Wednesday in a burning city, but the 32-year-old, who is on disability benefits, and his mom had no way to leave his downtown apartment. “Nobody picked us up,” said the man in a gothic-style black long coat, a metal chain wrapped and glued around his cane. He was also bused out of town and placed at a seniors’ lodge in Lac La Biche.

Back in mostly deserted Fort Mac, MacDonald Island Park recreation complex had gone from evacuee centre to an unofficial Alberta firefighters’ convention and reception hall. Local crews mingled with those from Edmonton, Leduc, Slave Lake and Crossfield. They ate barbecue, carried toiletry kits into the building, exchanged hugs. A crowd was gathering around one firefighter who had in his lap a black cat with white paws; he fed the recovered pet water from a styrofoam cup, and stroked its fur with his leather-gloved hands.

Brian Jean hugs an evacuee in Lac la Biche (Photograph by Chris Bolin )

Waterways, the city neighbourhood that dates back to Fort McMurray’s days as a big Metis trapping post, lay in complete ruins, including the home of Brian Jean, leader of the Wildrose opposition party. South across a valley sits the undamaged neighbourhood Gregoire. Up the hills and on the highway’s opposite side sat the remains of Abasand and Beacon Hill.

In south Beacon Hill, Google Street View shows houses in red and white and beige. Friday, there was nothing. Concrete steps led to a void. Aluminum car parts had become rivulets of silver down a driveway. Allen told media that his crews retreated from the field of flames in Beacon Hill and focused salvation efforts elsewhere. The fire spared little on Beacon Hill’s southern streets, but seemed to have a fondness for gardening effects. A stack of topsoil or manure bags sat piled on one property, and several homes over, a green metal patio table still held four undamaged plastic flower pots, along with a blue watering can with a smiley-faced sunflower as the spout. A Canada Post superbox also survived.

Past the destroyed Super 8 Hotel and Flying J gas station, black smoke lifted from small fires in the regional landfill, and several abandoned cars on the roadside were flanked by blackened grass. Low-flying planes flew overhead by a bloodshot sun to survey forest damage. The smoke was getting heavy enough that RCMP officers directing and halting traffic had to wear gas masks.

The next day at Lac La Biche’s Bold Centre, Howe was sporting a decidedly not-gothic grey Carhartt T-shirt, and had swapped his chain-wrapped cane for a walker. With at least two more weeks to go, he’ll take what he can get. He expects the next thing he’ll take is a government-supplied trailer. He’s trying to look at it as a long camping trip.

A Mountie walks through burned remains. 2,400 buildings were lost. (Alberta RCMP/Reuters)

Chapter Seven: The city will rise again

Canada’s need for a restored, fully operational Fort McMurray is beyond question. The disruption in production at the oil sands, estimated around one million barrels a day, or 40 per cent of the usual output, is expected to grind GDP growth to a near-stop during the second quarter of this year. It’s a testament to just how important the industry has become to the economy—even in a world of US$40-per-barrel oil.

How badly, though, do its residents need Fort McMurray? With the fire following so closely on the heels of the oil bust, it was clear some have lost faith. Sarah Davies, for whom those madly chirping birds augured catastrophe, had toiled for Work Authority, a safety apparel company. Now, having lost their home, she says, she and Abercrombie have decided not to go back. “There is nothing left there for us,” she says. “It’s all gone.”

Such resignation may affect not just the decisions of its workers, but the fortunes of its sustaining industry. Allan Dwyer, an assistant professor of finance at Mount Royal University in Calgary, wonders how many homeless oil sands workers will be eager to return, given the doom and gloom hanging over their sector—everything from the battles over pipelines to concerns about climate change. “There’s been a growing sense, as the global oil prices have gone down and stayed down, that the oil sands is somewhat of a sunset industry,” Dwyer says. “This only adds to that creeping negative sentiment.”

Already, some residents are raising hard questions about city’s forest-fire preparedness, and handling of the evacuation. Cassandra Benson, the student whose family bounced back and forth following evacuation orders, was one of several who told Maclean’s they found the decision-making haphazard, leaving too many people rushing to the city’s only highway out of town. For all the acts of bravery, an evacuation that funnels thousands of families through a gauntlet of fire can hardly be optimal.

Others question whether more resources might have been mustered to stop the fire. Horsnell, the Suncor truck driver who saw those initial puffs of smoke, previously worked with fire-suppressing water trucks in the oil sands. He now wonders why authorities didn’t harness the mammoth resources of private companies. “There’s enough water trucks in Fort McMurray that we could have surrounded that city with them, bumper to bumper,” he said. “If I had my water truck with 20,000 litres of water on it, my house would not burn.” (Private crews were in fact involved in the fight. A Syncrude-branded fire truck appeared in at least one drive-by video of a wrecked neighbourhood. And as oil sands retiree Del Keating slowly drove out of Timberlea to safety, he spotted giant, bitumen-stained D11 bulldozers rolling up to the community, which was largely spared. “That guy who made that decision, he probably saved a lot of lives,” he said.)

The fear and second-guessing could have a sapping effect on reconstruction efforts, just as workers and governments take a wait-and-see approach as to how much building is needed. Oil sands firms already bleeding money may also re-evaluate the scope of their commitment to the region. “A few years ago, when oil was trading around US$110 a barrel, there would be no doubt about it being an all-hands-on-deck approach to rebuilding,” Dwyer says. “Now it could be a different response.”

Still, those who helped build Fort McMurray are adamant: the city will rise again. Heather Campbell, 54, arrived in Fort McMurray on New Year’s Eve in 1984, and played her own part in its transformation from a stopover town to a place people called home. While her husband, Don, worked at Syncrude—he still does—she joined a family and community services team dedicated to encourage people to put down roots. “We didn’t want them to treat it as somewhere to send the men to earn money,” says Campbell, whose three adult children all live in Fort McMurray. “There was a really big push to make this a community where people would raise their children.”

The fruits of those efforts were visible in the city she fled on Tuesday (the family’s sprawling Thickwood home was spared). “Entire generations of families are staying,” she says. The loss of those families’ homes will be felt acutely, Campbell acknowledges. But the accoutrements of urban life the city had built up—its museum, rec centre, performing arts centre and library—remain intact. “I know people think we’re transient,” says Campbell, “that we’re just there for the money and the work. It’s so not true.”

The modern Fort McMurray has been largely ignored in stories by journalists who visited the Boomtown Casino, toured the oil sands sites, buttonholed a couple of Newfoundlanders outside a Tim Hortons and then went home. “We try to tell people: you’ve got it wrong,” says Fiske, the Suncor equipment operator. In addition to finding an audience for her poetry in the city, she has raised a son who makes a living there playing piano. “The trouble with Fort McMurray’s reputation is you get it from commuters,” she says. “They fly in, they hit a bar or something and they fly out.”

Perhaps the events of this week have forced outsiders to see beyond those stereotypes. Journalists from Britain, China, the U.S., France and—yes—Toronto have spent time in the organized chaos of Lac La Biche’s evacuee centre, meeting McMurray-loving Sudanese familes, moms rifling through tables of donated children’s clothing, and engineers reluctant to take handouts beyond a bottle of water.

(From left) Danielle Larivee, Rachel Notley and Darby Allen inspect the damage (Chris Schwarz/Government of Alberta/EPA)

And for every Sarah Davies, there appears to be several people like Brian Schaefer, the Minnesotan who’d been in the city only three weeks when the fire struck. Schaefer says he’s committed to stay, and not just because his marketing job is supposed to keep him there at least three years. He’s quickly developed a social network in town. Since decamping to Edmonton, he’s had waitresses pay for his family’s lunch, and seen a hotel lobby full of wedding attendees boisterously celebrate a stranger’s fifth birthday. “How could my family and I walk away from something like that?” he says. “Seriously, tell me.”

Kate Cox, the young Aussie who spent more time in flight delays than she did in Fort McMurray, is enjoying a similar sense of inclusion. She landed at her friend’s sister’s home in Athabasca, a four-person dwelling suddenly hosting 17 guests. For Cox, it’s a household full of new Fort Mac friends: she’s going to return when she can.

Even among the massive “shadow population”—the transient workers who couch-surf—there’s a desire to stay. Truck driver Derek Hicks’s wife and home are in Moncton, N.B. For 10 months a year, he hauls water and septic loads for Whitmoor Vac Services. The fire forced him south to an evacuee camp in Wandering River. But Hicks and his crew were high in demand, and he’s decided he’ll stay in Fort McMurray. “There’s going to be a lot of work here,” he says.

Little of that work will be pleasant, of course. The rubble removal alone will be a massive undertaking. The task of rebuilding homes will be colossal—the number of residences destroyed is greater than the number completed in the region in 2013, 2014 and 2015 combined.

On Monday, Premier Notley took stock of the wreckage. Yes, the 85 per cent of Fort McMurray left intact is every bit a thriving city. But 15 per cent of its structures are gone, and such a loss would cripple a community of any size. Yes, there’ll be insurance money and government money and the sense of shared purpose that has raised walls and roofs across Western Canada. But the events of the first week of May are burned into residents’ minds—with the knowledge they’re living on the ecological equivalent of a kindling pile—and no amount of lumber and shingle can restore the nerve of a badly rattled town.

For that, Fort McMurray will need its best citizens to come home, armed with the dauntless spirit that brought them there in the first place.

—with Michael Friscolanti and Chris Sorensen

advertisement

Published: May 12, 2016

Related reading

Want to help Fort McMurray? Here’s how

Fort McMurray Fire: Frequently Asked Questions