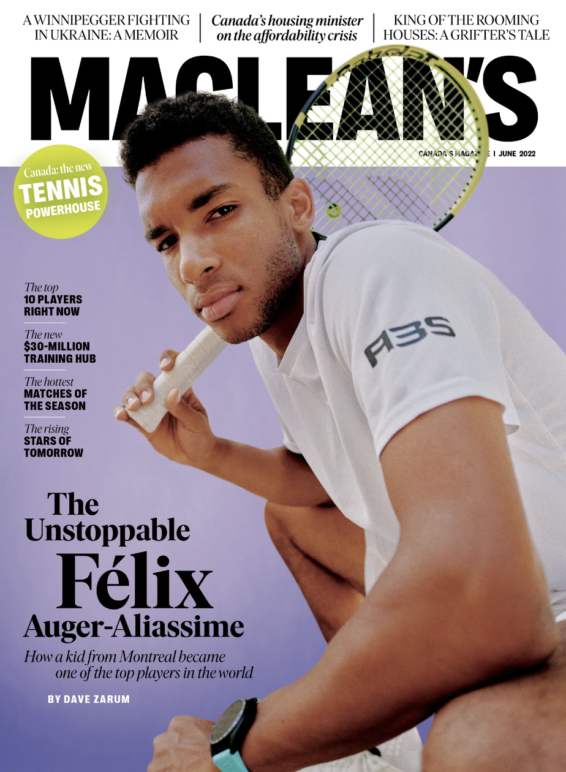

The rise of Félix Auger-Aliassime

The Montreal dynamo grew up fantasizing about being one of the best tennis players on earth. Now, he’s cracked the top-10. The hard part? Staying on top.

(Photography by Evaan Kheraj)

Share

This story originally appeared in the June 2022 issue of Maclean’s.

Félix Auger-Aliassime was seven years old the first time he caught a tennis coach’s eye. It was 2007, and Sylvain Bruneau, who was working with Équipes du Québec, saw hundreds of seven- to 10-year-olds take the court at the Montreal academy every other Saturday to play with friends. One day, among the mass of bright yellow balls ricocheting around the courts, Bruneau noticed a spindly kid who burned a hole with his eyes through each ball that came his way. It was hard to miss him. The child would bring his racquet back, line up his shot and, like clockwork, power the ball across the net, releasing a guttural grunt with each stroke—the kind of sound that a human can only produce when they’re pushing their body to its limit. Bruneau was absolutely floored. “Who is this?” he wondered.

While most kids were goofing around, Auger-Aliassime was preparing for a career. “He was serious,” says Bruneau, who has since worked with some of the top stars in the country. “He was able to concentrate in a way you don’t see from kids that age. It was…” he pauses. “Different.” The average kid doesn’t have his career mapped out at seven years old. Then again, Auger-Aliassime has never been average.

From the time his father first told him it was possible to make a profession out of playing the game he loved, Auger-Aliassime developed a one-track mind. “From that point on I was on a mission,” he says. “What never changed was my desire to make it and do this as my career. It’s pretty wild that at that age I knew what I wanted to do in life.”

Auger-Aliassime’s rise in tennis is no Cinderella story. He’s earned it. He has blazing speed to cover the court, serves like a rocket launcher and, at six-foot-four, the length to reach any ball. It’s all combined with a mind that’s as finely tuned as the engine of a luxury sports car. Now, Auger-Aliassime leads a deep and talented crop of young Canadian players making a name for themselves—and their country—on the global stage.

“Since he was young, he wanted to go to the top,” says his coach Frédéric Fontang. “In order to do that, you need to eat tennis. You need to sleep tennis. It becomes an obsession.” So far, the results speak for themselves. Last year, Auger-Aliassime made his Olympic debut, led Canada to an ATP Cup victory and became the youngest player since 2009 to play in the semifinals of the U.S. Open, the final grand slam of the calendar year. In the first half of 2022, he won his first major tournament and smashed his way into the top-10 world rankings, reaching number nine and entering this summer as the top Canadian men’s player on tour.

For this year’s grand slam season, the stakes have never been higher. “I like to be in this position,” he says. “When you’re on top of Mount Everest, the air becomes thinner. The question is: Are you going to survive?”

***

Tennis was inevitable in the Auger- Aliassime household. Félix’s father, Sam Aliassime, was born and raised in Togo, a small French-speaking nation in West Africa with no real tennis system in place, which has produced only a handful of pro players in its history. Sam, despite talent and a passion for the game, was not one of them. But he grew up admiring the tennis stars of the ’80s and ’90s, flipping through whatever magazines he could get his hands on and transfixed by the few matches he could find on TV.

In 1999, Sam emigrated to Montreal and settled down with his wife, Marie Auger, a teacher. Their daughter, Malika, was born in 1998 and, shortly after Félix came along in 2000, the family moved to Quebec City, where Sam got a job coaching tennis at Club Avantage, a large indoor rec centre in the quiet suburb of L’Ancienne-Lorette.

As a strict rule, Sam and Marie limited screen time for Félix and Malika, who were encouraged to play outdoors. They would explore nearby parks, inventing games and playing sports. Whether it was badminton or Ping-Pong, the rules were always the same: the first to reach 100 points wins.

They also inherited Sam’s love for tennis. “I picked it up quickly,” Auger-Aliassime says, with a hint of a French-Canadian accent. “It was always tennis, tennis, tennis.” After school, the siblings would accompany their father to the courts. Some days, Sam would give them lessons; other times, Félix and Malika would hit the ball for hours on end.

Félix was a natural at any sport he picked up. When he wasn’t immediately great at other pursuits, like piano, it drove him mad. The screen-time rule was relaxed when it came to tennis, and Félix was glued to players like Rafael Nadal, whose poster was on his bedroom wall. The siblings pushed each other to get better. Malika—who reached a junior ranking of 554 before turning her attention toward her education—admits she was rarely able to beat her baby bro after he started to outgrow her.

'When you're on top of Mount Everest, the air becomes thinner,' says Auger-Aliassime. "The question is: are you going to survive?'

At 10 years old, Félix won the Canadian under-12 indoor nationals. At 11, he won an international tournament for 12-year-olds held in Auray, France. He began travelling more, preparing for a life on the road. “He was never missing home or calling in tears,” says Malika. “He had this air of independence to him and carried himself like he knew this was what he needed to do in order to be where he wanted to be.”

Had Auger-Aliassime been born a decade earlier, he likely would have relocated to somewhere like Florida, where he’d have access to top-tier coaching and world-class competition. But by the time of Auger- Aliassime’s rise, Canada had its own world-class system to develop elite young players at home.

And so instead, he moved to Montreal at age 14 to join Tennis Canada’s National Tennis Centre, the high-performance factory established in 2007 by former French Tennis Federation coach Louis Borfiga. There, Auger-Aliassime began working with his first coach, Guillaume Marx, and Tennis Canada’s stable of instructors. He quickly earned a reputation for his intense practices, his determined grunts once again echoing through the facility—just like when he was a child.

In 2015, he won four junior tournaments and dipped his toes into professional waters. At a tournament in Granby, Quebec, at age 15, he became the youngest men’s player ever to win an ATP Challenger match. Even some seasoned pros took notice. “He is one of the players the future of men’s tennis belongs to,” noted Roger Federer, the game’s all-time great. “He is a very complete, elegant player.”

Frédéric Fontang was working as a freelance coach for Canadian star Vasek Pospisil when he was contacted by Borfiga, who told him to check out the rising star. From his home in Bradenton, Florida, Fontang watched one set of a match against an opponent ranked inside the top 150. On the tiny screen of his cellphone, Fontang observed the teenage Auger-Aliassime push far more experienced players to the edge. “It was not usual to see that kind of intensity,” he says.

***

Within two years of arriving in Montreal, Auger-Aliassime had gone from promising prospect to the number-two-ranked junior singles player in the world. But despite his unusual work ethic, there was still much to learn when it came to the inner game.

Tennis is a lonely sport. In singles, players are out on the court by themselves; they aren’t allowed to communicate with coaches during matches. It forces them to cope on their own. “You prepare with your coaches, but when it comes down to the court, it’s really a one-on-one challenge between you and your opponent. Nothing else matters,” says Auger-Aliassime. “You learn a lot about yourself.”

The isolation of tennis can make or break players. And one day in 2016, it nearly broke Auger-Aliassime. At 16, he’d entered the U.S. Open Juniors as one of the favourites to win it all. But he kept seizing up. In the second round against Australian Alexei Popyrin, Auger-Aliassime lost the first set in the best-of-three match. Exasperation set in. “As a kid I would get frustrated, and I’d show it. I used to get angry when a match wasn’t going well.”

In the second set, he missed a shot wide. Dejected and desperate for help, he looked toward Guillaume Marx in the grandstands. The coach turned away. After another error, he set his gaze on Marx again, who looked away once more. “At first, I was confused,” recalls Auger-Aliassime. “I felt abandoned. But I got the message: I guess I’m supposed to figure this out myself.”

Auger-Aliassime roared back to win the second and third sets and clinch the match. Afterwards, Marx pulled him aside. “There comes a time when you can’t play like that anymore,” he told his protege. “You can’t be looking at me—or anyone else—for answers.” At that moment, Auger-Aliassime says, his mindset shifted. “Eventually you learn that, if you really want to make a difference—not just in my sport but in life—you are the main actor. Only you are responsible. After that day, I was a different player.” A week later, after defeating number-five seed Miomir Kecmanović from Serbia, Auger-Aliassime was crowned the U.S. Open junior champion.

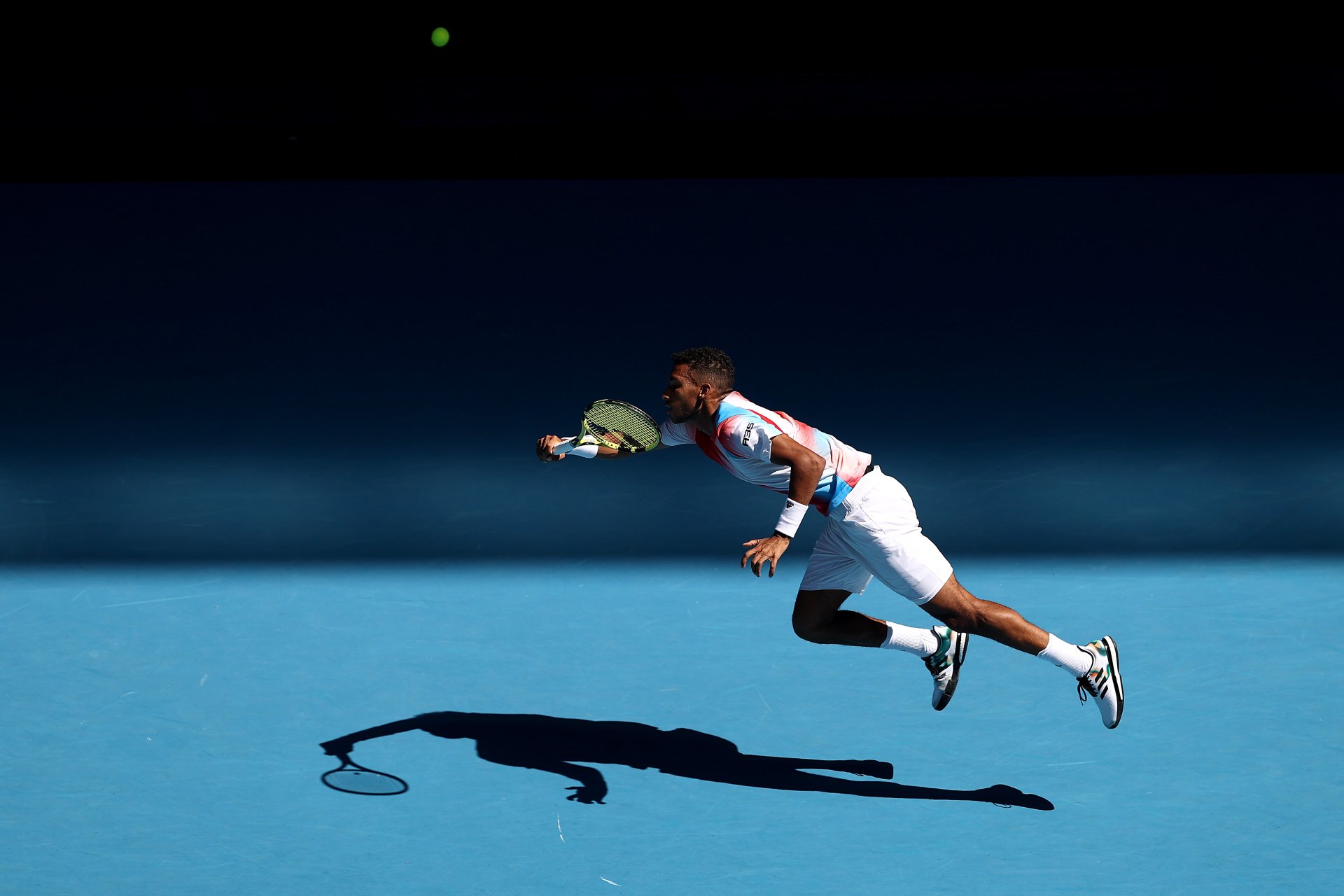

(Photo courtesy of Cameron Spencer/Getty Images)

When Auger-Aliassime is on top of his game, he’s playing chess and moving the pieces on both sides. Nowhere was this more evident than in July of 2021, on the iconic No. 1 Court at the All England club at Wimbledon. Auger-Aliassime showcased the evolution of his game in a four-hour-and-seven-minute battle against Alexander Zverev of Germany—whom he had never beaten despite three previous tries. During the milliseconds it took for the ball to reach him, Auger-Aliassime calculated his options. His eyes narrowed, each blade of freshly cut grass magnified as he zeroed in on a sliver of open court. “You have to decide: do I make him move once more?” he says. “Do I go behind his back? Do I take a drop shot? A ton of decisions in a split second.”

He opted for a booming forehand that sent Zverev to the corner, then positioned himself for his next salvo. A smashing volley at the net secured him the upset win and booked his ticket to the next round. “It was a big match and a turning point,” says Fontang. Two months later, Auger-Aliassime reached the semifinals of the U.S. Open. He had arrived.

Auger-Aliassime thrives in a sport built on swift decision-making. “I’m the type of person who, once I make my decision, I rarely second-guess it,” he says. “It’s like that when I buy things in a store or order at a restaurant. I don’t hesitate.” But some decisions require more time. Take, for example, the months-long process of choosing a new coach. Entering this year, Auger-Aliassime reached eight tournament finals—a huge achievement at such a young age. But he lost each time. His 0-8 finals record was the second-worst in tennis history. “At least one of us won’t have baggage weight issues at the airport,” he tweeted, clocking the size of his opponent’s massive trophy after losing the finals of a tournament in Marseille in February. He didn’t get angry; he isn’t one to smash his racquet. But he knew it was time for a change. “Arguably it’s a selfish decision,” he says. “But in an individual sport, sometimes you need to make a selfish decision.”

Auger-Aliassime moved on from Marx, who had been coaching him in tandem with Fontang, to bring somebody new on board in an adviser role—someone who had won grand slams and reached the pinnacle. He made a list of dream candidates. At the top of the list was Toni Nadal, the uncle and former coach of tennis icon Rafael Nadal, winner of a record 21 grand slams.

Auger-Aliassime reached out and, to his delight, Nadal agreed to work with him. They spent two weeks training at Nadal’s facility in Mallorca, where they hit it off immediately. “We talked about the values of excellence and work ethic—things that are so, so important to me that society tends to forget these days,” says Auger-Aliassime. “Like the value of repetition.” (Nadal has remained a part of Auger-Aliassime’s team, though Fontang continues to handle primary on-court coaching duties.)

Six months later, at the Rotterdam Open in January, Auger-Aliassime finally broke the losing streak, defeating Stefanos Tsitsipas, ranked number three in the world, in the final. “The player has to stay in the present moment, in the action. It was a big release, beating Tsitsipas. But I was already thinking about the following week,” says Fontang. “That’s the challenge.”

***

Auger-Aliassime’s rise coincides with an explosion of talent across Canada. Since the development of the National Tennis Centre in 2007, and Tennis Canada’s ambitious goal to have multiple Canadians placed among the top ranks of the sport, Canada has gone from tennis afterthought to budding powerhouse. With access to high-level coaching and training resources, we’re producing more elite talent than ever before. In 2019, Canada reached the finals at the Davis Cup—a tournament that pits nation against nation— for the first time in the event’s 122-year history. Auger-Aliassime was on Canada’s roster. Two years later, he led the country to victory this past February at the ATP Cup world event.

Today’s young stars have witnessed Canadians like Auger-Aliassime succeed on the global stage and are eager to make their own mark. It’s helped breed a confident and electric playing style—a new calling card of Canadian tennis.

After joining the professional ranks full time, Auger-Aliassime plotted his next move. Barcelona was an option and so was the south of France—both popular destinations for tennis pros. In the end, he chose Monte Carlo, a haven for many of the game’s elite players. Tsitsipas, Daniil Medvedev, Stan Wawrinka and others reside in Monaco, often training together between tournaments.

Each morning, the sun rises above the Mediterranean outside Auger-Aliassime’s window. For the first two years, his studio apartment was mostly barren, but now there’s art on the walls—mostly landscape paintings from local artists—along with framed photos of his family and girlfriend taken back home in Quebec.

Auger-Aliassime’s apartment is near the Monte Carlo Country Club, whose picturesque red-clay courts overlook the sea. It is the same club where Louis Borfiga, the man credited with turning around Tennis Canada, got his start. The club, which hosts a prestigious annual tournament, has become Auger-Aliassime’s home court and de facto training centre.

Playing a sport with virtually no off-season, Auger-Aliassime is on the road for most of the year competing in tournaments around the world. All told, he spends anywhere from 15 to 20 weeks in a given year at home. “I’m not meant to be stuck in Canada forever if I think it’s the best for my career to move abroad. Monaco was the best place for me. Even though it was a big move, I have zero regrets about it.”

Since he’s left his nest, Auger-Aliassime makes a point of getting his family together whenever possible. Each year during the tournament held at Indian Wells in California, the Auger-Aliassime clan rent a house in the city. Félix, Malika, Sam and Marie are there, along with Auger-Aliassime’s coaching staff. It’s an important chance to reconnect as a family. Sam, who ran a restaurant in Togo before moving to Canada, helps with the cooking. Marie brings maple syrup from Quebec. They gather around the table, discussing things like art and politics. (The war in Ukraine was a big topic this year.) But everyone keeps an eye on the tennis match on TV in the background.

While most young people chase a sense of freedom, Auger-Aliassime craves discipline. Every day is regimented, and that’s how he prefers it. “I’m not somebody who wakes up and says, ‘Okay, let’s see where the day goes,’ ” he says. “I like things in order. I like to have a plan, a vision. I’m a bit of a perfectionist.”

When he’s in Monaco, he’ll head to the country club each morning, drop off his bag in the mahogany-clad locker room and make his way to the red clay for two hours of on-court training. Then he’ll hit the gym for sport-specific fitness, followed by lunch and a nap. If there’s an imbalance between the game and down time, that is by design. “I know where I want to go. The way I see it, tennis is always my first priority,” he says. “I have high ambitions in my sport and want to do as well as possible.” Fitting, then, that he’s built a home in an environment where tennis comes first, second and third. “Things are not complicated,” Auger-Aliassime says. “I love what I do. I try to do it in the best way.”

Auger-Aliassime has gone from an up-and-coming teenager to a top-10 player with a target on his back.

After capturing the Rotterdam title in January and reaching the finals in his next tourney in Marseille, Auger-Aliassime was on a roll. By March, he’d defeated Andy Murray, Jo-Wilfried Tsonga and Andrey Rublev, and expectations for his 2022 season grew. Things have changed in a hurry for Auger-Aliassime. This year at Wimbledon, which begins at the end of June, he’s expected to make a deep run. As a junior, that weight of expectation made him nervous. Now he seeks it out.

In a few short years, Auger-Aliassime has gone from an up-and-coming teenager to a top-10 player with lucrative sponsorship deals with Adidas and Tag Heuer—and a target on his back. Naturally, his ascent to tennis’s top tier came with challenges. But none compare to the demands that come with staying there, and justifying the attention from tennis fans around the world. “I’ve always put a lot of pressure on myself in this sport,” he says. “But pressure makes diamonds. I want to be in a position where people are demanding a lot from me.”

Auger-Aliassime knows how far he’s come and how much further he still has to go. “How good I can be will depend on myself: how focused my work is, how hard I’ll compete and how resilient I’ll be over the coming years,” he says. “If I do these things well, I can go as far as I want. And yeah, sometimes I’ll lose. But always with a fight.”

This story originally appeared in the June 2022 issue of Maclean’s.