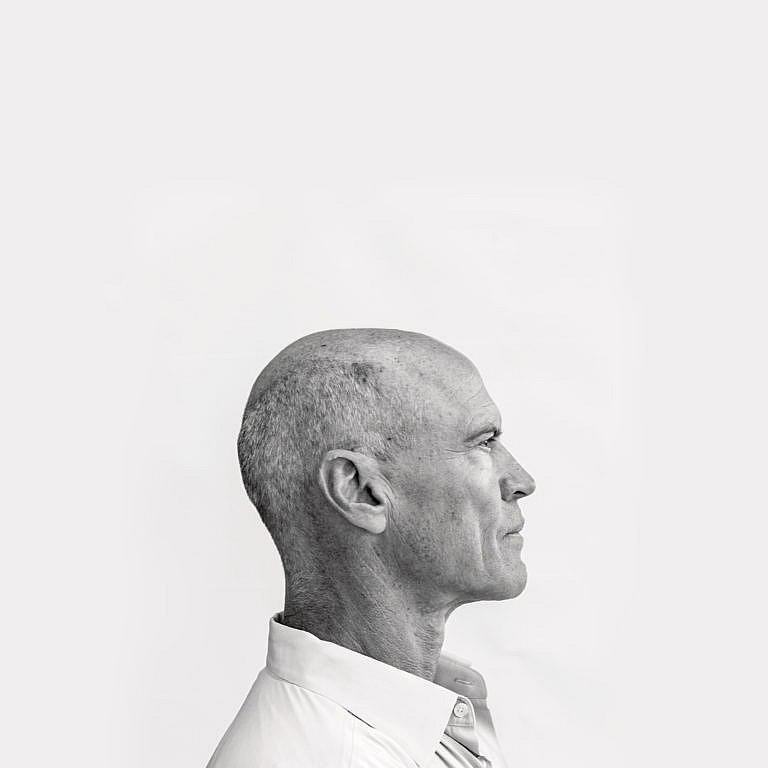

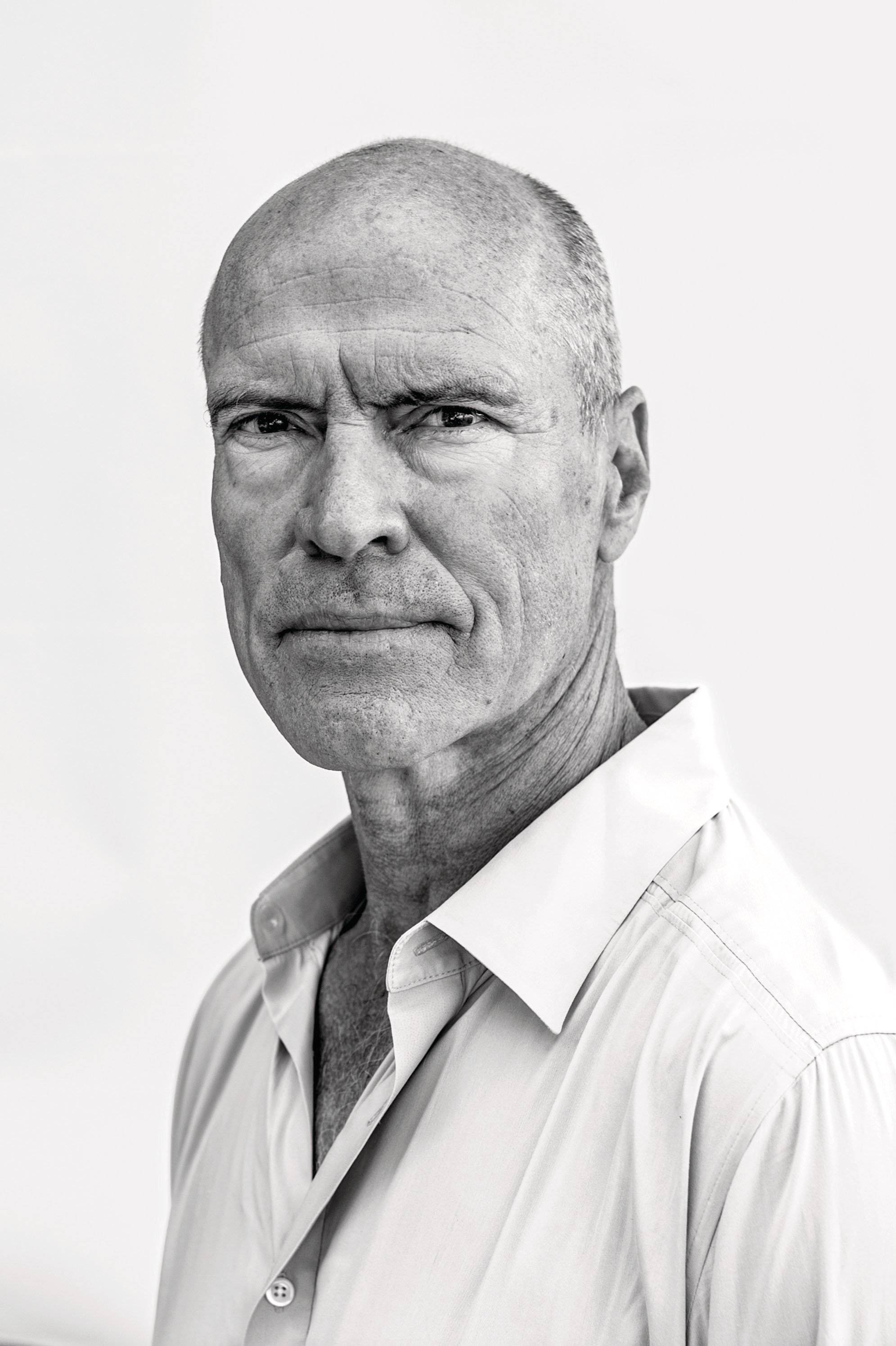

Mark Messier on leadership, trust and magic mushrooms

The hockey icon talks with Marie-Danielle Smith about mental health, hockey violence—and what he’ll do when the New York Rangers call

(Photograph by John Brackett)

Share

He’s a six-time Stanley Cup winner, the second most prolific playoff-points scorer ever, a two-time most valuable player in the NHL, a 15-time all-star and the only person ever to captain two different teams to Stanley Cup championships—the Edmonton Oilers, even after the departure of his great friend Wayne Gretzky, and the New York Rangers.

First he was “the Moose,” then he was “the Messiah,” according to New Yorkers—that’s a play on his last name—for ending a 54-year Stanley Cup drought in 1994. He’s an officer of the Order of Canada. And he’s now the author of a memoir he hopes will convey the lessons he learned along the way.

Mark Messier chatted with me ahead of the release of No One Wins Alone, authored with writer Jimmy Roberts. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Q: Your book is a meditation on leadership as much as it is a memoir. What’s the biggest lesson you’re hoping people will draw from it?

A: One of the questions I get all the time is: what’s the single most important lesson of leadership? I’m not sure there’s an answer because it’s so multidimensional. I do know that earning trust is just massive and earning the right to lead the people is critical. You know, Abe Lincoln said no man can govern another without his consent. You can’t expect to lead people unless you’ve earned that right.

Q: How do you earn it?

A: It always starts with trust. One of the most important things I did with the players I played with was getting to know them on a more personal level. Taking the time to understand where they came from. Understanding who they are as people and spending as much time as possible with them away from the rink so you develop a relationship that is deeper than a professional relationship.

John Wooden, a great basketball coach, said great coaching is being able to give correction without resentment. When you’ve got to be honest with a player and he might not like it but he doesn’t hold it against you or think you have something against him as a person. As a leader you’ve got to be able to go home at night and put your head on the pillow and know it’s up to him to resolve the issue.

Q: You talk about the importance of connection between teammates. Your relationship with Wayne Gretzky shines through as a critical one.

A: It’s not very often that you can look at someone eight days younger than you and look at them as a role model. Normally you get that from folks who are much older than you, who have been around with much more experience. But our best example was the same age as us. We’re all grateful that the stars collided and that we all came together at the same time.

Q: How important is it to see your teammates as friends?

A: When we talk about being brothers, I don’t think we reference each other like that lightly. Maybe you don’t need to have that in order to win, I don’t know—I didn’t have that experience on the teams I was fortunate enough to win with. Maybe you can win without that real tight level of friendship.

Q: How important is it to believe you’re going to win, and to be able to say that out loud?

A: I don’t think you can be afraid to fail. I think you really need to be forthright in your objective. For us in hockey at a professional level, you have a very defined goal of what success is. You can have smaller goals along the way and celebrate those goals, but ultimately you’re there for one reason and that’s to win a Stanley Cup. It might take some time to build a team and get some experience and put the pieces in place to do that. But you always have to have in the back of your mind on a day-to-day basis: are we closer to winning a Stanley Cup or are we further away?

And making sure that everybody in the organization, whether they’re on the ice as a player, or with a trainer or a doctor, physicians, therapists, equipment managers, managers, coaches, everybody is there with the same goal in mind, believing in the philosophy and the vision of the team and the culture the team created. Then you just start chopping wood and carrying water toward that goal.

Q: You probably get this question all the time, but is there a moment you would pick out as your ultimate career highlight?

A: To come to New York and win a championship that hadn’t been won in 54 years was incredible. And it’s pretty remarkable what happened in Edmonton, coming from an expansion team to winning the Stanley Cup, and going on to win five cups in seven years. I just can’t compartmentalize one moment in a career over 26 years. There’s too many special moments and they’re all different in their own rights.

Q: The game has changed a lot since you started playing, especially in the physicality. What do you think of how hockey has evolved?

A: I’m happy the game has evolved in so many ways. They’ve made changes to the game to get the speed and the finesse and the artistry back into the game, instead of hooking and clutching and holding and grabbing. They opened up the game to more excitement for the fans. It’s a better product when the game is played like that. There’s still plenty of physicality.

The equipment has changed. Technology has entered into hockey like every other sport, not only with the equipment but with the training. The players are making incredible use of science now to train all year round. So many things have advanced in the sport, but ultimately in the end the game is still won on the ice between the boards. It always gets down to a test of will, and that’s what makes hockey so great.

READ: Murray Sinclair on reconciliation, anger, unmarked graves—and a headline for this story

Q: There’s a scene in the book where your son is looking at old videos and he says something like, “You’d be in jail for some of those hits if they happened now.” How do you talk to your kids, and young people, about how things used to be and how much has changed?

A: I think we all recognize that as the game evolved and concussions started to enter into sports, if things didn’t change, the game wouldn’t last. So the game had to evolve and I’m glad both the NHLPA and the NHL took a collaborative effort to do that, and the players took the responsibility to change the way the game was played.

I don’t think anybody’s proud of some of the things that happened back in the day, but it was a different landscape back then. Intimidation was a huge part of hockey. [The game] evolved into something that is acceptable with all the social media applications and video reviews. You can’t get away with anything.

Some of our games back when I first started playing professional hockey weren’t even televised. There wasn’t even a camera in the rink. And we’ve brought the fans closer to the game. The fans are more knowledgeable about what’s going on, not only on the ice but also behind the scenes. The culture of professional sports is more exposed than ever.

Q: There seems to be no room for error with social media. What do you think about what young players are dealing with today?

A: There’s a different kind of pressure on the players now that we were never exposed to, socially, politically, and the choices they make and the way they represent not only the team but also the league and the community.

What it really boils down to is character becomes high-stakes, or of very high importance. To be able to handle it all. We don’t expect anybody not to make mistakes, mistakes are part of life, it’s how you learn, it’s how you grow, it’s how you evolve. So I think there’s some forgiveness for a mistake but there’s not forgiveness for a history of certain actions that aren’t acceptable anymore.

Q: Are you worried that forgiveness isn’t always extended to people who might deserve it? The online mob kind of picks its targets.

A: If you go down the rabbit hole of getting acceptance from people online, that’s a dangerous place to be. I don’t think it’s a good idea for anybody to be looking there for self-worth or validation, acceptance, because as we know there are people who just don’t have anything better to do who will be hurtful. It’s not a good place to be looking for that kind of information.

Q: Younger athletes are applauded today for talking about the pressure they’re under, and prioritizing their mental health even if it means taking time away from competing. Do you think that’s a good thing?

A: Everybody needs help no matter what position you’re in, no matter where you are in your own life. The biggest thing that has come out of all of this is that there’s no shame in admitting any problem, and seeking help has been very productive and helpful for a lot of folks.

Q: You talk in the book about conquering negative self-talk and learning to think positively about yourself. Were there times when that was hard for you?

A: I didn’t think about it much as a young player, to be honest with you. I had a lot of confidence. But everybody struggles. Even at the peak of my career I would struggle at times. I was fortunate enough that we had sports psychology seminars at a very early age, basically the first year of my career when I was 18 years old. I kept it with me my whole career.

Self-confidence is huge and a big part of that is self-talk—when things aren’t going well, not to be negative. You have to figure out what went wrong so you’re able to move on from any failure.

Q: You describe taking magic mushrooms at 19 as a transformative experience. Tell me more about how your perspective expanded.

A: Well that’s what it did for me. I had no idea the mind was that powerful. And how could eating a natural mushroom that was organically grown create that kind of stimulus? Obviously it turned out to be an amazing experience, but more important was the question afterwards: wow, how can I use my mind to empower myself to be a better player, to be a better person, to have more energy, to create a better aura?

So then I became interested in Eastern philosophy, meditation, Buddhism, the spirituality of Indigenous peoples. The power of the mind.

Q: Is spirituality still a big part of your life?

A: It’s always been a big part of my life. I grew up Catholic but was interested in a lot of Eastern philosophy. So I think spirituality became more important to me than the so-called religion I grew up with.

Q: You obviously took leadership lessons from these philosophies. You even end the book with a quote from a Hindu text.

A: There are so many powerful lessons to be learned about the goodness that lives in everybody’s heart. And creating a culture that is just so rich with humility and passion and creativity and all the things that make it fun to come to the rink, or to come to work. It’s the essence of a team that can go all the way. A unique environment with the diversity of the players, of where they come from, and their ideas. And really acknowledging that and letting people shine in their own ways.

Q: You talk about the importance of diversity and making people feel comfortable, but people of colour haven’t always felt comfortable in the NHL. What are your thoughts on that?

A: I know a huge mandate—from the NHL, the NHLPA and everybody involved with the league—is to grow the game. Diversify the game. Give more kids—more girls, more boys—access, opportunity. And it just makes sense. The Kingsbridge [Armory] project I was doing in the Bronx, that’s what it was for, to grow the game and its diversity by creating access and opportunity that are just not there right now. The NHL has immersed themselves in communities and they’ve taught boys and girls the game of hockey who’ve become fans and who are going to continue to get more people of colour involved in the game.

RELATED: Black hockey players on loving a sport that doesn’t love them back

Q: Do you think that in the past there were failures of leadership on this?

A: I can’t speak to that myself. I don’t know enough to say yes or no. I think creating access and opportunity is a huge first step.

Q: Would you be tempted to get involved in the NHL again as a coach or a manager?

A: I think I’ve always felt I could help an organization in many ways. But it’s important to be with people who believe you can help. If it happens, great. If it doesn’t happen, that’s okay as well. If the occasion ever came where someone thought I could help them, I would be more than happy to have that conversation.

Q: If the New York Rangers called, would you go for it?

A: I don’t work in hypotheticals. If the right person thought I could help their team, I’d be more than willing to listen.

This article appears in print in the November 2021 issue of Maclean’s magazine. Subscribe to the monthly print magazine here.