A century later, a vicious anti-Greek riot in Toronto offers lessons for today

In 1918, three days of riots took aim at Toronto’s Greek immigrants—revealing who gets to be seen as part of Canada’s fabric, and why

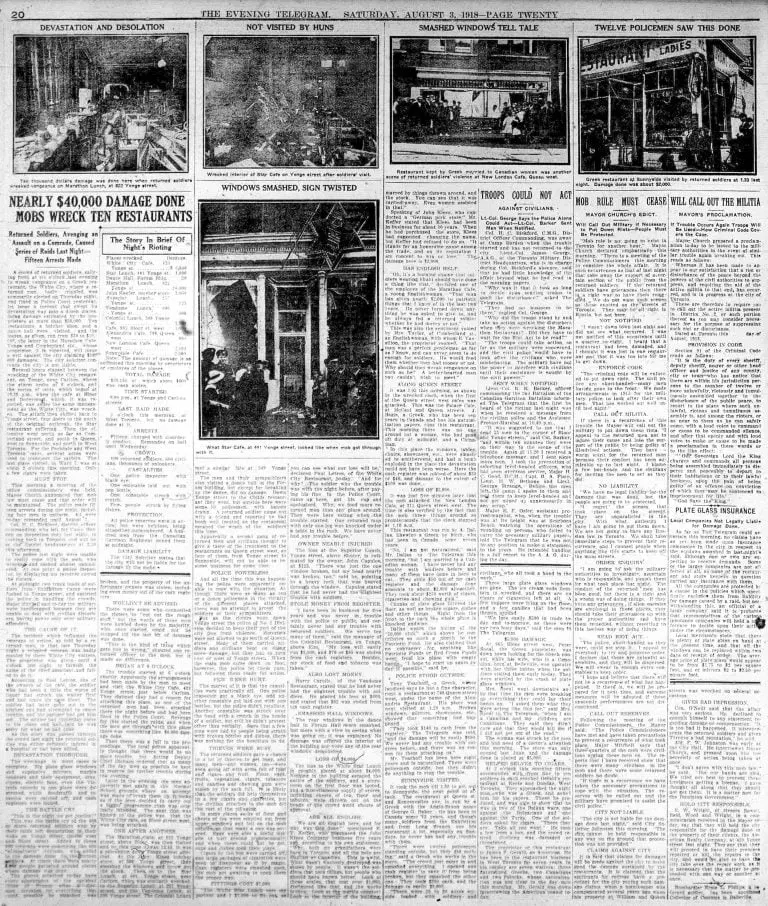

The evening Telegram from August 3, 1918, page 20.

Share

Toula Drimonis is a Montreal-based freelance writer, editor, columnist, and TV panelist. A former news director with TC Media, her byline has appeared in the New York Times, The Cut, Ms. Magazine, National Post, National Observer, and many other publications. She is currently writing a book on the immigrant experience.

Aug. 2, 1918, was a scorcher of a Friday in Toronto. The heat and humidity hung like a suffocating wet blanket over the city as thousands of veterans gathered in town to attend a congress of the Great War Veterans’ Association, with the formal end of that long and brutal fight just months away. Canadians were lining up the casualties and veterans were ready to voice their simmering grievances about how they felt they were being treated upon their return, finding cities that didn’t look like they did when they went off to war. And just the night before, a Canadian army veteran decided that he wanted to eat dinner at a café in Toronto’s burgeoning Greektown along Yonge Street—until his booze-fuelled aggression led him to be removed from the restaurant.

What would happen next, amid these raw nerves in this heated moment, would have far-reaching impacts on the city of Toronto as we know it today. The seemingly innocuous ejection of a bellicose veteran would wind up triggering the biggest race riot Toronto has ever known, and one of the largest anti-Greek riots in the world. The riots would also permanently alter the face of the city, driving the Greek community out of the neighbourhood they had carved out near Yonge and, eventually, into an eastern corridor named Danforth Avenue. And by the time it was all over—after then-mayor Tommy Church invoked the Riot Act and called in the military police—hundreds would be injured, many would be arrested, and damage to Greek property would total more than $1 million by today’s values.

One hundred years later—just weeks after Toronto’s Greek community was shattered again, this time by a shooter named Faisal Hussein—the anti-Greek riot also tells us how the forces that led to that first conflagration still exist to this day, and how deceptive and dangerous rhetoric, endured for so long by various immigrant groups, can easily slip into violence.

Claude Cludernay, by all accounts, didn’t want a part in any of that—the army private just wanted dinner at the corner of Yonge and Carleton streets, which at the time was near the business and residential hub of Toronto’s Greek immigrant community, stretching a few blocks in the heart of downtown. But Cludernay, who had been drinking, wound up assaulting a waiter at the Greek-owned White City Café, and he was asked to leave. A rumour, however, began to circulate among veterans that it was the other way around: that one of “their own” was kicked out of a café by “slacking” immigrants—and from a country perceived to be in the pocket of the German enemy, no less.

Indeed, at the time, Greece was seen as apathetic at best to the Alliance cause in the First World War—even though that was hardly the case. Greece was in fact a friendly neutral to the Alliance at the beginning of the war, with Greece’s King Constantine insisting on neutrality simply because it was the best strategic policy for the country, even as others suspected his German dynastic lineage prevented him from openly siding against Germany. Then-Greek prime minister Elefterios Venizelos, however, wanted to bring Greece into the war on the side of the Allies, something he eventually would do in 1916, two years before Toronto’s race riot.

READ MORE: The history—and the meaning—of Toronto’s Yonge Street

But the forced neutrality during the war’s early years—which prevented Greek-Canadians from being allowed by the government to fight on behalf of Canada—didn’t help Greek immigrants abroad. The fact that these able-bodied and young Greek men went about their business in high-visibility restaurant and public market jobs made some Canadians consider them ungrateful in not contributing to Canada’s war effort. This misinterpretation would prove to be tragically ironic, too; two decades later, during Germany’s Second World War occupation of Greece, more than 56,000 Greeks would be executed in cold blood by Axis forces.

Those false perceptions merely served as unfortunate kindling for a firestorm of hate, violent looting, and bubbling xenophobia in Toronto. At about 6 p.m. on Aug. 2, 1918, veterans began to gather, according to historian Thomas Gallant, the co-author of The 1918 Anti-Greek Riot in Toronto. By 7 p.m., 600 of them had gathered outside the White City Café. “A fusillade of rocks and bricks smashed through the windows and doors of the restaurant,” recounted Gallant in the documentary Violent August. “The mob then entered inside, destroying every scrap of furniture, every counter, and then looted the kitchen.

“As they told their fellow soldiers: tonight they wanted justice,” Gallant continued. “Tonight, they would go hunting Greeks.”

Hundreds quickly became thousands, and from the corner of Yonge and Carleton they would head northwest to the corner of Bloor and Dufferin, destroying every Greek-owned business they came across, while the police looked on and did nothing. “By 1:20 a.m., the mob demolished the Alexandria Café at 748 Queen Street West,” said Gallant. “Owner Tony Tsarhoof begs police to intervene, but they refuse. The mob hurls him to the ground and he watches as his café is destroyed.”

By Saturday night, Toronto police and the city administration, criticized for doing little to stop the destruction, retaliate with brutal force, hitting the rioters indiscriminately, injuring many veterans and innocent bystanders in the process. By Sunday morning, the city—now on lockdown—is reeling from the riot. Across the city’s sidewalks, blood and broken glass is splayed on the sun-warmed asphalt.

This was also a time in which Greeks were not seen as many do today—that is, as white. David R. Roediger, a professor at the University of Illinois and the author of Working Toward Whiteness: How America’s Immigrants Became White, wrote that those considered “white” generally came from England, the Netherlands, Ireland, Germany and Scandinavian countries. So Greek immigrants were viewed with suspicion in North America—as a foreign incursion that threatened the job prospects of local citizens—as evidenced by a 1909 pogrom-style riot in Nebraska which resulted in the death of a Greek boy, the burning of Greek-owned businesses and homes to the ground, and the displacement of South Omaha’s Greek population. “Herded together in lodging houses and living cheaply, Greeks are a menace to the American labouring man—just as the Japs, Italians, and other similar labourers are,” Joseph Pulcar, the editor of the Omaha Daily News, wrote at the time.

Greeks were even the targets of the Ku Klux Klan. The American Hellenic Educational Progressive Association (AHEPA)—one of the largest Hellenic heritage groups in the world—was founded in 1922 in direct response to the racism and bigotry Greeks experienced in the U.S. at the hands of the KKK. While it’s a barely mentioned part of the Greek diaspora’s history today, the Greek population was, in fact, terrorized by the racist organization who saw all immigrants and people of colour as below them. “The Klan in the Western States has a great mission of Americanism to perform,” Fred L. Gifford, Klan Grand Dragon of the Realm of Oregon, in Atlanta, said in a 1923 speech. “The rapid growth of the Japanese population and the great influx of foreign labourers, mostly Greeks, is threatening our American institutions, and Klans in Washington, Oregon and Idaho are actively at work to combat these foreign and un-American influences.”

The KKK also organized boycotts of Greek-owned confectionaries and restaurants, occasionally even amplifying its tactics by openly threatening or attacking customers who entered or left. “Greek establishments doing as much as $500 to $1,000 a day business, especially in the South and Midwest, dropped to as little as $25 a day,” James S. Scofield wrote in a 1997 article for AHEPA. “The only recourse was to sell or close.”

So the Greek diaspora in North America took action. According to Roediger, Greeks and other immigrant groups slowly started on a “path to whiteness” to access the better prospects that white privilege bestows as a reaction to the anti-immigrant sentiment they faced. AHEPA founders were adamant about demonstrating that “Greeks were good Americans and good for America, and therefore desirable business associates and beneficial citizens,” according to the organization’s manual. During the Second World War, for example, AHEPA sold more than $500 million of U.S. war bonds, more than any organization in America, in part because of its overwhelming desire to be accepted into American society and give back. And many Greeks shortened or changed their long or difficult-to-pronounce names in an effort to assimilate quicker into American society, making them less of a target of suspicion, and less of the “other.”

To this day, not much has changed on that front: there is still generally opposition to immigrant groups until assimilation occurs to the country’s liking. Immigrants must continue to bear the burden of proving their value and ability to behave like “the rest of us” in terms of religion, composure and language. Toronto’s other major race riot offered similar lessons; in 1933, a baseball game at the city’s Christie Pits park turned into a brawl pitting Jewish and Italian Canadians against those who displayed a swastika, which had become common as a way to threaten Jewish people, who had been banned from summer resorts, from swimming at public pools. The Christie Pits riot reveals how Jewish people and Italians, too—groups that are clearly part of the city’s fabric, today—had to work to be seen as equal.

And Greeks, too, have become part of that fabric. According to the 2011 census, 252,960 Canadians claimed Greek ancestry that year, with about half living in Ontario; 43 per cent of Ontario’s Greek population lives in Toronto. Second-generation and third-generation Greeks can be found in Parliament, the Senate, on our national broadcasts and on the Supreme Court of Canada. And more than a million people gather every year at Toronto’s Greektown on the Danforth for Greek cuisine and other revelling.

But the integration of so many immigrant groups has appeared so seamless—contributing daily to the country’s economic vitality and diversity and forming an integral part of who we are and how we live together—that it can be easy to forget that racial tension and violence has been extended in the past to nearly all the groups who have successfully made their home here in Canada. Indeed, these people who are now in the warp and weft of Canada are the descendants of immigrants, asylum seekers, and refugees who were interned in concentration camps, or who had their property seized and their livelihoods ripped away, or who knew of the stories of their compatriots being turned away at our shores to face certain death at home, or who ran up against racial quotas at our biggest universities, or had their businesses destroyed by Canadians who, sensing them as the reason for their own dissatisfaction, just didn’t want them here. All it takes is a single spark to light a potential tinderbox.

It’s not meaningfully different than today’s reactions to refugees and immigrants from Muslim-majority countries—a vulnerable community now under assault simply because of the last name of the shooter who killed two on the Danforth, the home of a community that had to suffer and endure and heal and work to assimilate before they could be seen as being shattered by senseless violence.

As the federal election nears, politicians may stir anti-immigrant fears for their own benefit. Misleading and xenophobic portrayals of immigrants may yet increase. So it is important to be vigilant and hold fast to the lessons of the 1918 anti-Greek riot: that as welcoming and accommodating as Canada can largely be, anti-immigrant sentiment is as Canadian as maple syrup, and often just as sticky. It’s a story that plays itself out generation after generation, and immigration wave after immigration wave. Unfortunately, we can never seem to remember what the riots already clearly told us: given time, safety, and the essential instincts of immigrants’ nature, everyone—no matter where you’re from—can become part of our collective landscape.