A First Nation’s epic wait for clean water gets longer

Ending Neskantaga’s 25-year boil water advisory next month was supposed to be a symbolic achievement for Ottawa. Instead, it’s shaping up to be a symbolic failure

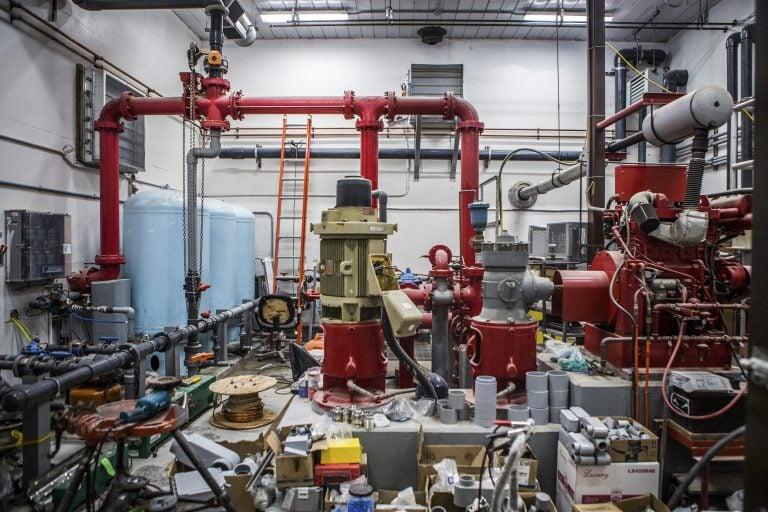

The water plant at Neskantaga First Nation.

(Photo by Chris Donovan)

Share

Residents of the Neskantaga First Nation, an Oji-Cree community about 450 km north of Thunder Bay, Ont., have lived without clean, safe drinking water from their taps for the past 25 years—it’s the longest-lasting boil water advisory among First Nations in Canada. The community expected a new water treatment facility to be completed by March. Now their long wait to have their advisory lifted will be even longer.

On Wednesday, Neskantaga’s chief and council terminated its contract with Kingdom Construction Limited (KCL), a company based in Ayr, Ont., while also passing a band council resolution to banish the workers from the northern community.

At a press conference held on the First Nation, Chief Wayne Moonias cited frustration with construction delays. He noted that May 30, 2018 was the water system’s original expected date of completion, but, “as of today, we are about eight and a half months behind” with “no clear end in sight.”

“Our First Nation believes that this is the best decision that will enable us to move forward and ultimately provide clean, safe and reliable drinking water to our community,” Chief Moonias said.

The community plans to take over the project and will seek an independent review of the infrastructure, and from there it will determine who will be awarded the contract to complete the work.

READ MORE: Not a drop to drink

Featured in a Maclean’s article earlier this year, Neskantaga’s water crisis offers an extreme look at what daily life is like trapped under a long-term advisory; where locals rely on purified water from a nearby reverse osmosis machine that regularly breaks down or freezes; and where other issues like mould-ridden homes and a youth suicide crisis compound an already pressing concern for the people who live there. “It’s hard boiling water all the time, and sometimes I’m tired of it,” Gloria Atlookan, the community health representative at the local clinic, told Maclean’s.

Chief Moonias said Wednesday that people in Neskantaga “have exhausted their support for the reverse osmosis unit that was put in as an interim measure,” adding that Indigenous Services Canada needs to decommission the filtered machine and provide the community an unlimited supply of bottled water.

Casey Moonias, a 26-year-old mother of three, has never turned on the tap in her community and drunk from it. She refuses to wash her toddler son, Meeson, in the community’s tap water. Nor does she ever consumer it. Instead, her family fetches jugs of water from the reverse osmosis machine several times per week. Residents in Neskantaga have frequently cited an itchiness on their skin that can last more than an hour after showering, as well as rashes and infections that they believe are caused by something in the water. Like others in the community, Casey is forced into ration-bathing. “I try not to get any in my mouth or open my eyes,” she said.

Neskantaga’s contaminated water is the result of a treatment facility that was built incorrectly in the early 1990s. Ottawa has provided more than $500,000 to the community to pay for bottled water since the advisory was issued.

The deprivation of drinkable water appears to be one force driving people away from the community—even if they want to stay. Roughly half of the First Nation’s registered population now lives in centres like Thunder Bay and Sioux Lookout, Ont.

RELATED: Money alone won’t solve the water crisis in Indigenous communities

The delay is an enormous symbolic setback for a government that’s trying to make good on an election promise to end all boil-water advisories on reserves by March 2021—an initiative seen as a keystone of Trudeau’s renewed relationship with First Nations. (Ottawa has lifted 78 long-term drinking-water advisories since 2015, and 62 remain.)

Speaking to Maclean’s last December, former Indigenous Services Minister Jane Philpott said the construction crew on the ground in Neskantaga was applying the finishing touches. Around this time, Chief Moonias voiced concerns about construction delays. The community’s water operator Wilfred Sakanee shared the same skepticism, describing the progress as “very, very, very slow.”

Wednesday’s announcement marks further tension between Ottawa and Neskantaga, and points to the community’s increasing frustration with how the feds are communicating the situation on the ground. In response to the chief’s concerns last November, Anne Scotton, director general for the Ontario region with Indigenous Services Canada, told Maclean’s that Chief Moonias “may have been misinformed” about the timeline of construction.

In a statement on Thursday, Rachel Rappaport, press secretary with the newly appointed minister of Indigenous services, Seamus O’Regan, said the lack of clean drinking water on First Nations like Neskantaga is “unacceptable,” adding that the Trudeau government is “firmly committed to working with the community to complete work on their water infrastructure.”

A statement from departmental officials said Indigenous Services is “working diligently with the First Nation to lift the long-term drinking water advisory and ensure that the community has a reliable water treatment plant that provides safe, clean drinking water and meets the community’s long-term needs.”

Funding for infrastructural projects on reserves comes from Indigenous Services, while the First Nations themselves determine the contractor. Rappaport said that feds’ engagement with selected companies varies on a “case-by-case basis” and by the “needs of the community.” In the case of Neskantaga, according to the department, the feds committed $8.8 million for the new plant and system back in July 2017.

For now, it’s unclear whether the fallout could result in legal ramifications between Neskantaga and Kingdom Construction Limited. Reached on Thursday, an official with KCL declined comment, saying the company would issue a statement in a week or so. Rappaport said questions about why the company was asked to leave should go to the First Nation.

On Thursday, Chief Moonias directed questions about the dispute to the First Nation’s lawyers, who were not immediately available for comment.

MORE ABOUT INDIGENOUS PEOPLES:

- By including Indigenous peoples, the USMCA breaks new ground

- Justin Trudeau offers the lowest of low-hanging fruit to Canada’s Indigenous peoples

- Few Canadians ever set foot on a First Nations reserve, and that’s a problem

- On First Nations issues, there’s a giant gap between Trudeau’s rhetoric and what Canadians really think: exclusive poll