On First Nations issues, there’s a giant gap between Trudeau’s rhetoric and what Canadians really think: exclusive poll

From self-government to public apologies, a comprehensive survey by the Angus Reid Institute suggests Canadians and their government are on completely different pages when it comes to the future of Indigenous peoples

Doug and Linda Johns walk through the Mohawk Institute grounds on May 26, 2018. Doug had spent several years at the Mohawk Institute Residential School. (Photograph by Andrew Lahodynskyj)

Share

From the front steps of her home in Brantford, Ont., Linda Johns looks down the street toward the Mohawk Institute, one of Canada’s oldest residential schools, and says she wishes they’d simply “torn the damn thing down.” The building is currently under renovation to “save the evidence,” as the fundraising campaign for repairs puts it.

Linda has visited the grounds as a tourist with her family, years ago, and says it was awful what happened to Indigenous youth there over the decades, “but now that we’re adults, I don’t care to hear about it. What they’re trying to do is blame other people for the problems they have now.”

She says Indigenous Canadians should have unique status in this country, but equally feels that, through our government, we are “almost climbing over ourselves to apologize” for past transgressions. As for federal spending on First Nations issues, Johns accepts that Indigenous people in northern areas need the money, but she says: “Around here, I think they could get off their butts and work.”

Her husband of 38 years disagrees. For starters, he wants the Mohawk Institute restored: it will serve as a reminder to Canadians of what the residential school did to him when he went there. “The food was terrible. You never got enough to eat. When it came for roll call to make sure everyone was still there, it went by number, not by name,” Doug Johns recalls. “It was almost like being in a prison.”

READ: For Indigenous boy whose braid got cut, the meaning of long hair makes it worth the taunts

The front steps of the institute—where Doug was forced to relocate at the age of 10, away from his family on the nearby Six Nations of the Grand River; where he saw classmates beaten for speaking their native tongue; which he first ran away from when he was 12, by way of country fields on a winter night to avoid police detection; where an abusive schoolmaster with a riding crop was more than willing to issue Doug lashings to his rear after every failed escape—are about 100 m from his front porch.

Linda says she doesn’t understand why her husband would want a building where he was so poorly treated to still stand. “She’s not Native,” Doug says of his wife. “We don’t see eye to eye on all these issues.”

Neither does the rest of the country. The most comprehensive public opinion survey on Indigenous issues since the Trudeau Liberals took office has uncovered deep fractures over key questions facing First Nations and the rest of Canada, suggesting the current government’s promises of reconciliation may be as hard to deliver as ever. The findings of the nationwide survey from the non-profit Angus Reid Institute point to divergent yet entrenched attitudes on both symbolic and existential questions.

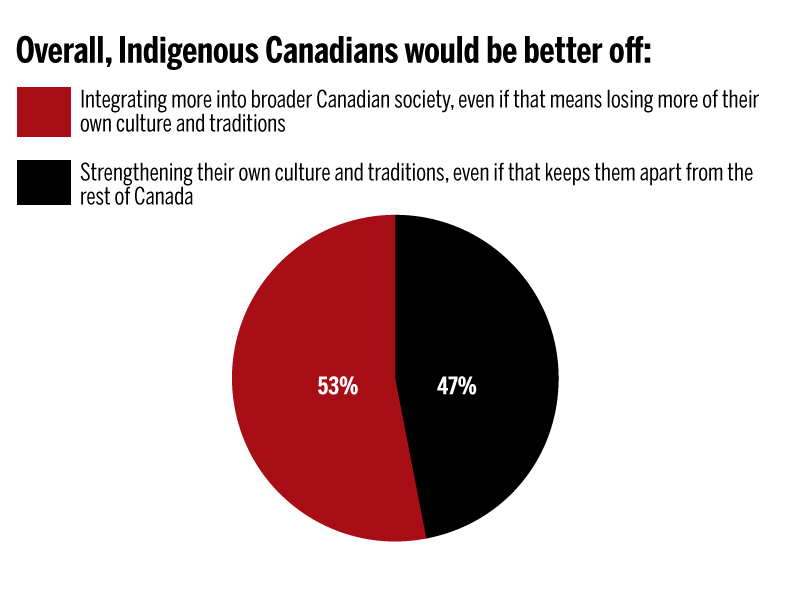

Fully 53 per cent surveyed said the country spends too much time apologizing for residential schools and it’s time to move on (compared to 47 per cent who believe harm done by the schools continues and cannot be ignored); more than half of respondents said Indigenous people should have no special status that other Canadians don’t; the same proportion said Indigenous peoples would be better off if they integrated more into broader Canadian society, even if the cost is losing more of their traditions and culture. Such ideas are, to put it mildly, anathema to the future many First Nations people—and the politicians who advocate on their behalf—envisage.

The wide-ranging survey, provided exclusively to Maclean’s, polled nearly 2,500 Canadians, and deliberately oversampled in regions with high Indigenous populations, only to uncover solitudes that the Johns household neatly encapsulates: sympathetic yet resolved; divided yet finding ways to co-exist. “This country is split down the middle on many of these questions,” says pollster Angus Reid in an interview. “It tells me the perspective of Justin Trudeau and [Minister of Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs] Carolyn Bennett on some of these issues is certainly not shared by a lot of Canadians.”

The wide-ranging survey, provided exclusively to Maclean’s, polled nearly 2,500 Canadians, and deliberately oversampled in regions with high Indigenous populations, only to uncover solitudes that the Johns household neatly encapsulates: sympathetic yet resolved; divided yet finding ways to co-exist. “This country is split down the middle on many of these questions,” says pollster Angus Reid in an interview. “It tells me the perspective of Justin Trudeau and [Minister of Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs] Carolyn Bennett on some of these issues is certainly not shared by a lot of Canadians.”

Sheryl Lightfoot isn’t surprised to see a divided public opinion at this point regarding Indigenous issues. “Given the heightened attention to them since 2015, with the shift in government to the Liberals, I could see it enhancing that polarization because people will view it—depending on their perspectives—as either too much or too little,” says Lightfoot, who holds a Canada Research Chair in global Indigenous rights and politics at the University of British Columbia. “What we’ve got is a country that’s woefully uneducated on Indigenous history and issues. Or they are living it every day and are close to it. There isn’t a lot in the middle.”

READ MORE: Want common ground on First Nations issues? Start by fixing the water supply

A lack of contact, familiarity and exposure defines Canadian relations with First Nations issues in many ways—most importantly by relegating them to the bottom of the political agenda. For decades, politicians have shied away from debating Indigenous matters regarding public policy, says Ken Coates, senior fellow in Aboriginal and northern Canadian issues at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute. “There’s been an implicit assumption in the Canadian political process for decades that if you had parties say we should do more [for Indigenous people], you’re not going to win many votes, so stay away from it.”

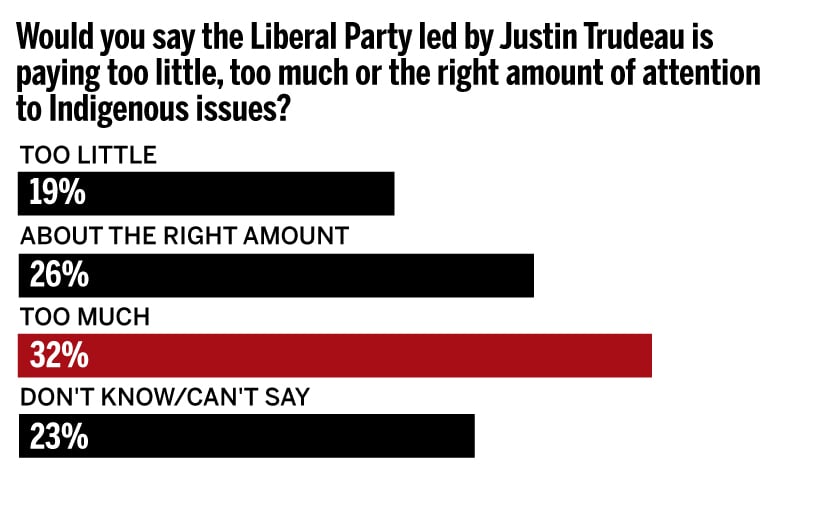

As such, the Trudeau government deserves credit for “moving ahead with something they feel is important,” Coates adds. But the fact that fully a third of Canadians polled feel Trudeau gives too much attention to Indigenous issues, compared to 17 per cent who feel he gives too little, highlights a gap in how the country prioritizes this relationship. (The rest are divided, saying either Trudeau gives them the right amount of attention, or they’re unsure.) “So long as you have a public that doesn’t believe Indigenous issues are a big deal, or doesn’t understand their context, then those issues are going to persist,” says Tunchai Redvers, co-founder of We Matter, a national support campaign for Indigenous youth. “Look at the Colten Boushie case.” When a Saskatchewan jury acquitted farmer Gerald Stanley for the 2016 shooting death of Red Pheasant First Nation resident Colten Boushie, the Prime Minister said, “There are systemic issues in our criminal justice system that we must address.” Trudeau’s words of support for the family of the deceased 22-year-old drew support from advocates, but scorn from others who felt he’d undermined the court’s authority and independence. In what has become a common avenue to express public support, a GoFundMe page set up for the Stanley family “to recoup some of their lost time, property and vehicles that were damaged, harvest income, and sanity” garnered more than $220,000 in donations in three months—surpassing the $200,000 in GoFundMe donations for Boushie’s family over a nine-month span.

When a Saskatchewan jury acquitted farmer Gerald Stanley for the 2016 shooting death of Red Pheasant First Nation resident Colten Boushie, the Prime Minister said, “There are systemic issues in our criminal justice system that we must address.” Trudeau’s words of support for the family of the deceased 22-year-old drew support from advocates, but scorn from others who felt he’d undermined the court’s authority and independence. In what has become a common avenue to express public support, a GoFundMe page set up for the Stanley family “to recoup some of their lost time, property and vehicles that were damaged, harvest income, and sanity” garnered more than $220,000 in donations in three months—surpassing the $200,000 in GoFundMe donations for Boushie’s family over a nine-month span.

READ: In Saskatchewan, the Stanley verdict has re-opened centuries-old wounds

The Boushie case points to one of the survey’s most puzzling findings: that non-Indigenous Canadians with regular exposure to reserves were more likely to take a rigid stance on Indigenous issues.

The institute found that Canadians are divided into four groups of roughly the same size on most questions: those who advocate for First Nations self-determination; those sympathetic to Indigenous people; those wary of Indigenous people asserting their priorities; and full-on hardliners who oppose special status and accommodation. “Western Canadians tend to be more hardliners,” Reid says. “Quebec has very liberal attitudes, but it’s also where we have the least likelihood of contact.”

Hardliners—a group that encompasses nearly a quarter of the sample—unanimously said Canada spends too much time apologizing for residential schools, and almost unanimously felt Indigenous Canadians should have no special status, while 85 per cent of them said Indigenous people would be better off if they integrated into broader Canadian society. “The hardliners are not racist, but they don’t buy the idea of separate status,” Reid says. “I think what the hardliners are saying is they don’t think the answer to the issues confronting Indigenous communities is going to come through more spending, but it’s going to come through improved leadership in Indigenous communities and through a heavier emphasis on integration.”

RELATED: The trickery behind Justin Trudeau’s reconciliation talk

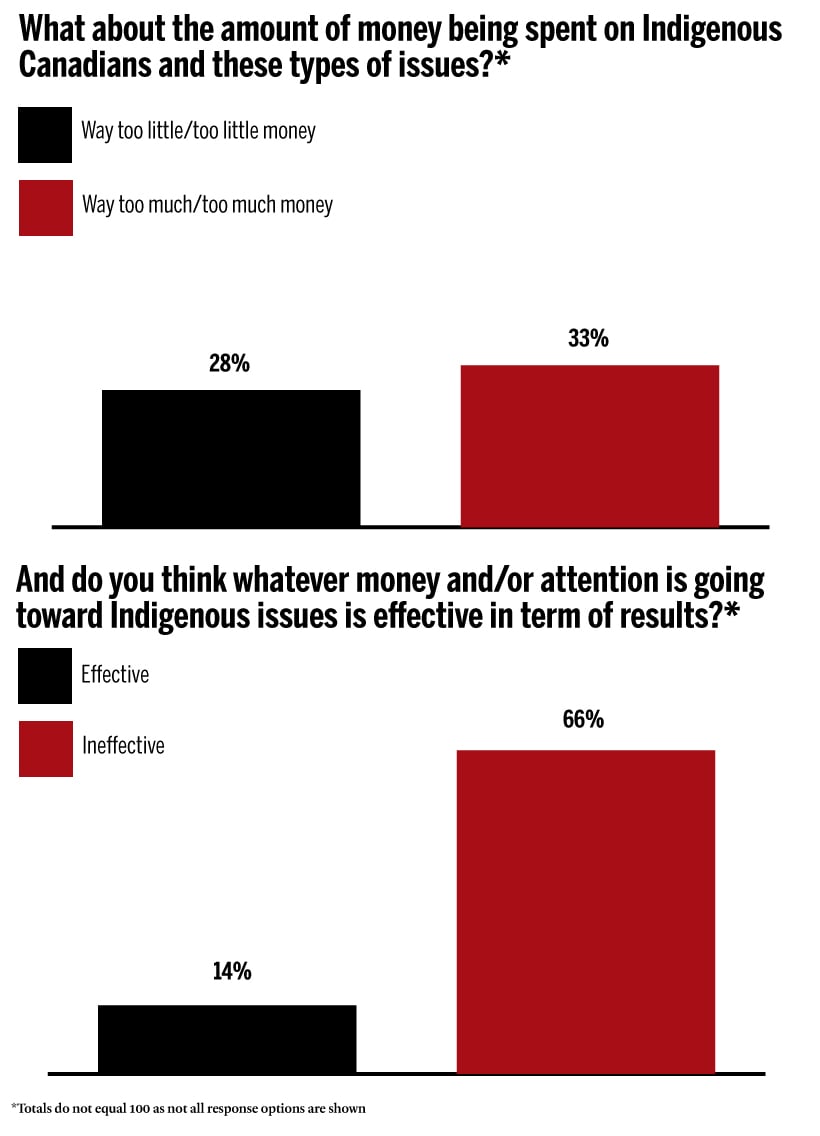

If there’s one thing respondents to the Angus Reid Institute survey agreed on, it’s that tax dollars meant to help First Nations people are generally failing to do so. Two out of three said government funds going toward Indigenous issues are generally ineffective—and a new report from the auditor general’s office will hardly quell that pessimism. Among other things, it found that data on high school graduation rates on reserves left out students who dropped out prior to Grade 12, meaning the department overstated the graduation rate by 22 percentage points.

Similarly, Employment and Social Development Canada—despite 30 years of supporting Indigenous employment—didn’t collect data or measure whether its key skills development fund resulted in Indigenous people getting steady meaningful work. Back at Six Nations, Doug Johns credits Trudeau with good intentions, but asks, “How many terms will he get to serve before he gets any of that accomplished? It would take two or three terms to see anything really done.”

Canadians might not have that kind of patience. Indeed, the survey results raise the question of whether a politician might succeed by taking a hardline stance on Indigenous issues. No mainstream leader is running on an explicitly integrationist platform, or argues the government should stop apologizing for residential schools. But Sen. Lynn Beyak published on her website letters of support from Canadians on these exact issues after she commented about the positive outcomes of residential schools. Her actions prompted Conservative Leader Andrew Scheer to call some of the letters “simply racist” and booted Beyak from caucus for refusing to remove them. But other letters voiced opinions that, while taboo, have a discernible market.

As it stands, only a third of Canadians believe Indigenous communities should move toward greater independence and control over their own affairs, according to the survey, compared to two-thirds who feel First Nations communities should be governed by the same rules and systems as all Canadians. Kim Baird, former chief of the Tsawwassen First Nation in B.C., wonders whether Canada has attained a critical mass of people who grasp basic truths about residential schools and the foundation of the country. “There needs to be more knowledge about the systemic reasons why reserves don’t look like other places, why they’re trapped in poverty, why there’s a lack of resources and infrastructure. It’s such a complex story to unpack. I think the residential school story is a good starting point.”

The Mohawk Institute, alas, will remain closed for a while, though visitors can take a virtual tour of the grounds. Before the work began, Doug Johns took his own kids through the school’s deserted corridors. He showed them where he ate, where he slept and the visitors’ room, where he got the whip for his attempted escapes.

He recalls new students getting beaten for not speaking English; because of the language barrier, they couldn’t understand why they were being punished. He remembers it being a “terrible place,” with fights often erupting on the grounds. “The whole idea of residential schools was to kill the Indian and save the child,” he says. “A lot of non-Native people aren’t aware of that, so I want them to restore the institute so people can see it.”