Where you live may decide how soon you die

Groundbreaking study looks at life and death by neighbourhood

Stephen Brookbank

Share

On March 6, Maclean’s hosts a town-hall discussion, “Health care in Canada: what makes us sick?” focusing on the social conditions that affect the health of Canadians, especially those in impoverished neighbourhoods. Held at the McIntyre Performing Arts Centre at Mohawk College in Hamilton, in conjunction with the Canadian Medical Association, it will also be broadcast on CPAC. The conversation about the health effects of disparities in income, education, housing and employment will continue in the coming months in the magazine, and at town halls in Charlottetown and Calgary.

What if you could see the future? What if you could see a young pregnant woman walking down Barton Street in Hamilton’s depressed north end and know her unborn child had already lost life’s lottery; that his or her fate was predetermined by Mom’s postal code?

You would know that this mother—in this neighbourhood, and in the bottom 20 per cent of the city’s income earners—is six times less likely than the wealthiest Hamiltonian to seek first-trimester prenatal care, and more than six times as likely to be a teenager or to have dropped out of school. You’d know the chances of her baby being born underweight and needing weeks in neonatal intensive care would also be higher.

And the child’s life would get no easier thereafter. If its parents lived an average life in this neighbourhood, they would die an average Third World death—at 65.5 years of age. If they lived five or six kilometres away, say, on Rice Avenue in the city’s leafy suburbs, they would live beyond 86 years.

What if you knew one of the world’s most advanced acute-care health facilities was here in Hamilton, yet was powerless to change the fate of this mother-to-be? What would you do?

What’s to be done is the challenge facing Hamilton and communities across Canada. The statistics are among the findings of Code Red, a groundbreaking analysis of life and death in 135 Hamilton neighbourhoods and census tracts. The multi-part series was written by Hamilton Spectator investigative reporter Steve Buist in collaboration with Neil Johnston, an epidemiologist and faculty member in McMaster University’s department of medicine.

The social determinants of health—income, housing, education, employment, early childhood development and race—divide us as certainly as any caste system. Where you sit on the income gradient sets your life course, determining how well you live and how soon you die. Divide Hamilton into income quintiles, and the average age of death for the wealthiest 20 per cent is 81.4 years. Death comes years earlier with each step down the income ladder. By the bottom rung, the poorest 20 per cent of Hamiltonians die at 69—12 years sooner.

The social determinants of health—income, housing, education, employment, early childhood development and race—divide us as certainly as any caste system. Where you sit on the income gradient sets your life course, determining how well you live and how soon you die. Divide Hamilton into income quintiles, and the average age of death for the wealthiest 20 per cent is 81.4 years. Death comes years earlier with each step down the income ladder. By the bottom rung, the poorest 20 per cent of Hamiltonians die at 69—12 years sooner.

Working on Code Red left Johnston feeling outraged at the waste of human potential, he said in a recent online presentation. He recalled how today’s hardest-hit inner-city neighbourhoods were thriving communities 40 years ago until the city was gutted by the decline of well-paying industrial, steel and manufacturing jobs, and by an exodus to the suburbs. “The chasm between neighbourhoods in the downtown core and the suburbs in determinants of health and health-service use is perhaps the single most important reason why Hamilton may never again be able to regain the relative prosperity it enjoyed 40 years ago,” he said.

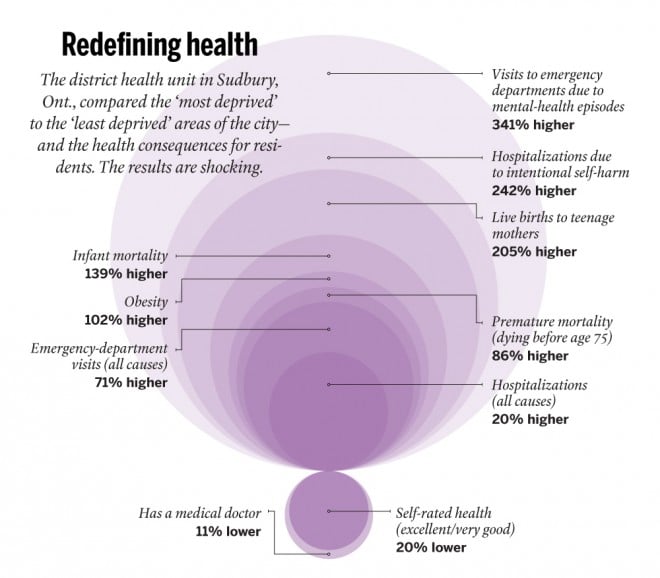

The phenomenon isn’t unique to Hamilton. The district health unit in Sudbury, Ont., is a strong advocate for redefining what makes us healthy, and has compared the “most deprived” and “least deprived” areas of that city. Among the most deprived: births to teenage mothers were 205 per cent higher; infant mortality, 139 per cent higher; and premature death, 86 per cent higher. The health region in Saskatoon also looked at health disparities in their city. In six low-income neighbourhoods, rates of infant mortality were 448 per cent higher; teen births, 1,549 per cent higher; and suicide attempts, 1,458 higher. “Moral reasons aside, it is in our collective interest to reduce social disparity,” the health region concluded.

Focusing on non-medical social problems is a priority for the Canadian Medical Association (CMA), which advocates for a sustainable, equitable and more effective health care system. Health is more affected by socio-economic factors than by doctors, drugs and hospitals, CMA president Anna Reid, an emergency room doctor in Yellowknife, said in an interview. “We feel we have a responsibility—a duty, actually—to start advocating for policies that change people’s life circumstances.”

If society must be fixed in order to heal the individual, where does one begin? Reid concedes doctors don’t have the answers. “We’re not the experts on how to fix the housing crisis, [although] we certainly are the experts on seeing the downstream effects of people who have no housing,” she said. “We don’t know how to fix the education system, but we know that if you don’t have an education, this is what it’s going to do to your health.”

Studies find the problem is a lack of accountability and inadequate budgeting for such necessities as housing, education, social services, child care, policing and other non-health determinants, which rest with different levels of government, each responsible for one puzzle piece that rarely fits into a complete picture. Experts say it’s a jurisdictional nightmare and an excuse for inaction.

Dennis Raphael, a professor of health policy at Toronto’s York University, has written extensively on Canada’s missed opportunities and the false economy of neglecting the web of social determinants. Canadians are among the world’s leading researchers on issues such as the health effects of poverty on early childhood development, but the results are more likely to be implemented in Scandinavia and European countries like France and Germany, where the concept of a welfare state is not dismissed out of hand, Raphael says.

While Canada spends heavily on a health care system designed to fix the sick, it’s a middling performer among fellow wealthy nations in health outcomes and in value for money spent, according to a much-ignored 2009 Senate report, A healthy, productive Canada: a determinant of health approach. Fully 75 per cent of factors influencing health rest outside the health care system, it found. “Passively waiting for illness and disease to occur and then trying to cope with it through the health care delivery system is simply not an option.”

Sudbury’s is among the health units working to shift government priorities. It produced a short video, Let’s start a conversation about health . . . and not talk about health care, which has been picked up and modified by health authorities across Canada, says the unit’s Stephanie Lefebvre. As manager of health equity, one of Lefebvre’s roles is to bridge the divide among a range of services and to ensure that the potential health impacts of local initiatives are considered in advance.

In Hamilton, Code Red has inspired changes including implementation of a nurse-family partnership program to guide high-risk mothers, and incorporation of the implications of social determinants into McMaster University curriculums for health professionals. It influenced McMaster’s decision to build its new $86-million health campus in the inner city, where it will provide primary care to an underserved population and give medical students an understanding of the challenges residents face.

Mark Chamberlain, a successful Hamilton businessman and a member of the city’s round table on poverty reduction, knows many people who live in the city’s blighted neighbourhoods. “They’re fantastic people, but their health outcomes aren’t determined by how fantastic they are and how much they volunteer,” he says. “Once they know where a baby is born from a postal code perspective—based on not changing our scenarios in how we invest—they can pretty much predict the outcome of that child, when and how they’re going to die.”

It’s a glimpse of a future he can’t accept, and one he’d like to think there is growing determination to change.

The Hamilton town hall will be moderated by Maclean’s Ken MacQueen, with opening remarks by Dr. Anna Reid, CMA president. The panel features Debbie Sheehan, former director of Hamilton’s family health division; Dr. Dale Guenter, department of family medicine, McMaster University; Mark Chamberlain, member of the Hamilton round table for poverty reduction; and John Geddes, Maclean’s Ottawa bureau chief.