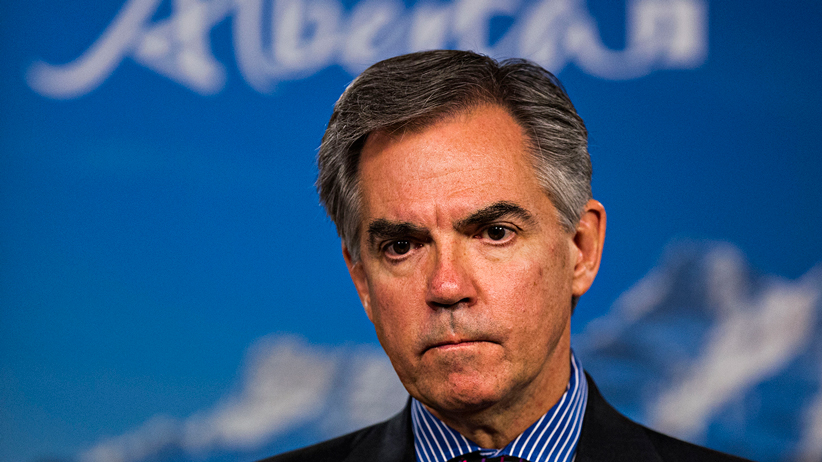

Divide and conquer: Jim Prentice’s by-election strategy

How the Alberta premier plans to try to save his increasingly unpopular, scandal-plagued PC party

Alberta Premier Jim Prentice speaks about the licence plate situation at the Alberta Legislature Building in Edmonton, Alta., on Thursday, Sept. 18, 2014. Prentice said there will be no new licence plates.

Share

There’s an Internet meme about whether it’s wisest to fight a horse-sized duck or a hundred duck-sized horses. Believe it or not, there is a correct answer to the question. Always choose to fight the duck-sized horses: They can, unlike a single creature, be defeated in detail. Napoleon or Bruce Lee would never, never have gotten this question wrong.

And neither would Alberta Premier Jim Prentice. Prentice, the former federal minister who won the Progressive Conservative leadership on Sept. 6, has arranged for himself and his two key ministers to bid for the legislature in simultaneous by-elections scheduled for Oct. 27. There will be four contests in all, three in Calgary and one in Edmonton.

If he had staked his leadership on a lone contest, Prentice would have faced concentrated efforts from strong rivals hailing from no fewer than four opposition parties. One of them might easily have emerged from the pack as the embodiment of anti-PC outrage, exhaustion, and impatience in Alberta, whose government turned 43 in August. The danger of a slip-up or “gaffe” would have been extreme. A single by-election may have attracted more national attention than a complicated five-parties-in-four-ridings pie-fight, and might even have invited troublemaking pollsters onto the stage.

Instead, the premier chose duck-sized horses. And make no mistake: It was a conscious choice. Prentice had to persuade four PC incumbents to leave the Assembly, giving up attractive MLA salaries and expenses at the same time. At least one of them, Calgary-West’s Ken Hughes, had announced in September that he would stay on until the general election scheduled for the spring of 2016.

Hughes is close to Prentice, as nearly everyone in Alberta politics seems to be, and said he would retire from the Assembly only if Prentice needed his seat. Prentice chose to run in Calgary-Foothills, vacated by aspiring federal Conservative MP Len Webber, but Hughes quit anyhow. The premier’s two immediate precursors, Alison Redford and Dave Hancock, also bowed out in a sportingly early fashion.

Dividing the enemy is a natural strategy for Prentice to pursue at this moment in Alberta politics. Albertans feel the world price of oil almost instinctively, the same way a rheumatic old gentleman knows what the weather will be like an hour from now. The spot price of West Texas Intermediate, which grazed $108 a barrel in the summer, is south of $83 at the time of writing. Inventories are swollen. Expected world demand for oil is being revised down. U.S. production continues to explode.

This is not as bad for Alberta’s budget as it might seem. International oil majors are backing off from planned oil-sands projects, but production from completed ones is ramping up, and Alberta labour markets are as tight as ever. The Canadian dollar is absorbing some of the pain from the glut, and the U.S.’s return to being a huge oil exporter is actually good news for Alberta oil-patch manufacturing businesses, without necessarily knocking Alberta oil out of its mid-continental markets. To some degree, Alberta has evolved economically to become for tight-oil applications what Texas and Oklahoma were—and still are—to conventional drilling.

But Albertans don’t like to hear whispers of a possible OPEC price war on expensive oil producers. That category includes the oil sands, as Prentice has emphasized—perhaps even overemphasized. It is a natural thing for him to stress, as the leader who is meant to use his environmental credentials and his special relationship with Aboriginals to force Alberta oil into new foreign markets. The more that voters are talking about this grand imperative, the less time they are spending talking about the PCs’ recent record of illegal political donations, interest-group bribery and Redfordian megalomania.

Prentice’s division of the enemy’s efforts does not mean he will carry all of his colleagues into the Alberta legislature with him. Perhaps the toughest fight is in Calgary-Elbow, where Education Minister Gordon Dirks is hoping to succeed Redford. Dirks, 67, is a unique figure. In his younger days, he was associated with the Canadian Bible College and Theological Seminary in his native Saskatchewan. He became a minister in the ill-fated Conservative government of Grant Devine, returning to the evangelical world—with his personal reputation intact—when the Saskatchewan Tories were brought low by scandal. The Bible college moved to Calgary as his first political career was ending, and he went with it.

This led to a second life as an Alberta civil servant, a leading Edmonton churchman and, eventually, chairman of the Calgary Board of Education, where he was a tribune for school choice—and a critic of the provincial PCs’ slow-moving school expansion. With his swearing-in as education minister, Dirks earned the almost unheard-of distinction of having served in the cabinets of two different provinces.

Prentice is backing Dirks by bolstering the PCs’ already-lavish promises of new school construction. Thirty-five new schools were announced in 2011, and 50 more last year: The premier now says 55 more will go up, eventually. The opposition says it is all smoke and mirrors. Meanwhile, Dirks makes for a slightly awkward fit with the ultra-posh and socially liberal Elbow riding. He has had to deflect complaints about his affiliation with a long series of institutions opposed to homosexuality, including the Calgary church to which he currently belongs.

Dirks and Prentice held a summit meeting with Kris Wells, a University of Alberta professor who has become the province’s political boss on sexual-minority issues. Wells says he received a verbal assurance of support for the dignity and comfort of lesbian and gay students, and gave a tentative green light to Dirks, saying, “I’m willing to give the minister the opportunity to live up to his commitments.” That will help. And Prentice’s track record of voting for same-sex marriage in the House of Commons will help more.

But the opposition parties of the left are still feeling good about Calgary-Elbow, where last spring’s floods left behind embittered homeowners snarled in red tape. The Alberta Party, an assemblage of vapourware with powerful alleged friends who never run for it and don’t seem to vote for it, is convinced that its leader, Greg Clark, has the potential to shock Dirks in the by-election.

Meanwhile, in Edmonton, Stephen Mandel is hoping to saunter to victory in the Tory stronghold of Edmonton-Whitemud. He carries some baggage from a nine-year Edmonton mayoralty characterized by tax increases and a sweetheart arena deal for the Oilers. As health minister, he is squaring off against a (New Democratic) doctor, a (Liberal) nurse, and even a (Green party) biologist.

PC candidates are accustomed to fending off grumpy health care workers, and they’re good at it. But the endless organizational turmoil in the province’s unified health authority—Alberta’s single largest employer—is a legitimate embarrassment. So, too, is the increasingly ruinous condition of Edmonton’s Misericordia Community Hospital, which sits just across the North Saskatchewan River from the Whitemud riding.

In Edmonton, it is the provincial New Democrats who may have the best hope to blacken a PC eye. Their latest leadership contest concluded on Oct. 18 with a victory for Rachel Notley, a labour lawyer whose father, Grant Notley, led the party from 1968 until his death in a 1984 plane crash. The elder Notley, killed going home from the capital to his remote northern riding, is remembered with affection as a lone frontier hero of ideological defiance during years of Conservative electoral and cultural dominance.

But the dynastic aspects of Notley’s victory, while compelling, are not the most important factor. The race she won was characterized by impressive fundraising numbers. Within Edmonton, recent polls have the NDP level with other parties, or even narrowly in first. National Leader Thomas Mulcair’s summer appearance in the city was a quiet triumph, and local New Dems are champing at the bit for the 2015 federal election.

The Whitemud by-election may be considered something of a dress rehearsal.