How one of Canada’s Most Wanted was set free

Michael Friscolanti explains how one of Canada’s most sought-after fugitives was captured with much fanfare—and then set free

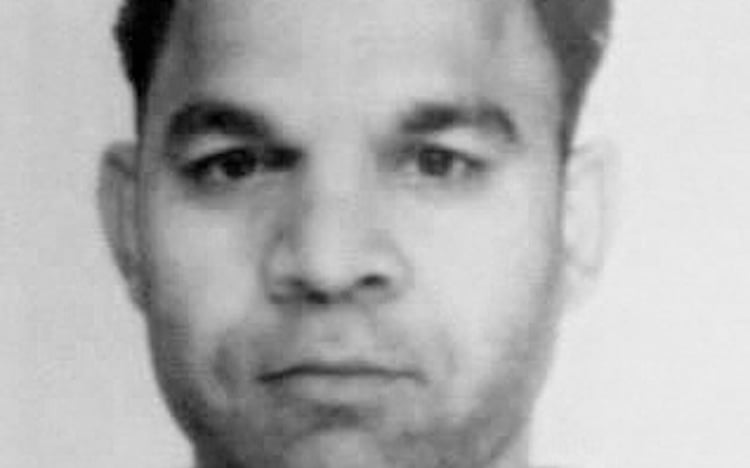

Arshad Muhammad is shown in this undated handout from from the Canada Border Services Agency. A war criminal who is on a list released by Canadian border security officials has been arrested. Arshad Muhammad, a 42-year-old from Pakistan, was arrested Saturday in Mississauga, Ont. after a member of the local police force spotted him in a store. THE CANADIAN PRESS/HO-Canada Border Services Agency

Share

One of the first suspected war criminals featured on the Canadian border agency’s “Most Wanted” list has been quietly released from jail—nearly three years after the Harper government celebrated his high-profile capture and promised the public that such fugitives “will find no haven on our shores.”

Arshad Muhammad made headlines in July 2011 when he was recognized and arrested in Mississauga, Ont., just one day after his mug shot appeared on a new FBI-style website launched by the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA). A failed refugee claimant and alleged member of a Pakistani terrorist group (which can’t be named because of a publication ban), Muhammad had been living on the lam for nearly a decade, working cash-only construction jobs and hiding behind bogus identities. Finally in custody, a swift deportation seemed inevitable.

At a post-arrest press conference, then-immigration minister Jason Kenney said Muhammad’s capture validated the controversial new Wanted list. “Those who have been involved in war crimes or crimes against humanity will find no haven on our shores,” added Vic Toews, the public safety minister at the time. “They will be located, and they will face the consequences.”

Almost three years later, Maclean’s has learned that Muhammad is once again a free man, discharged from Toronto’s Metro West Detention Centre on May 24 after agreeing to a list of undisclosed bond conditions. Of the 56 foreign fugitives flushed out of hiding by the Wanted list, he is one of the rare few to be released from jail while his deportation proceedings inch through the system.

For a federal program launched with such fanfare, it is an embarrassing development—though not exactly surprising. Muhammad has repeatedly argued, with some success, that he should be allowed to stay in Canada precisely because the feds chose to publicize his name and photo. Canadian law prohibits the government (except in extremely rare cases) from removing illegal residents who could face cruel and unusual punishment in their home countries, and Muhammad insists that by publicly branding him both a war criminal and a suspected terrorist, Ottawa made him a prime target for torture if flown back to Pakistan.

In other words, he says, the same website list that finally tracked him down has also made him impossible to remove.

Many Canadians will have little sympathy for his stance. This is a man, after all, who snuck into the country with a fake Italian passport, claimed—then denied—he was a member of a terrorist organization, and promptly vanished after his asylum claim was rejected. How can plastering such a person’s face on a Wanted list now spare him from deportation?

His argument, though, has not fallen on deaf ears. Even before the list went live, it was a question that concerned senior bureaucrats: By finally identifying the border service’s most-wanted illegal immigrants, would the government actually jeopardize its chances of deporting some of them? A CBSA briefing note, since disclosed under the Access to Information Act, specifically warned that the “release of this information would highlight a person’s case to the public, potentially leading to the person being at risk when removed.”

From his detention cell, Muhammad applied for a pre-removal risk assessment (PRRA), a process that determines whether an illegal resident would be in danger back home; the first step is an “opinion” rendered by an immigration officer. In October 2011, an officer sided with him, concluding that the two heavily publicized labels now attached to his name (war criminal and terrorist) make “it more likely than not” he would be at risk if deported to Pakistan, where terrorists, real or imagined, are routinely tortured. (A separate assessment, conducted by the border agency, also concluded that Muhammad is not a security threat in Canada and never directly participated in any criminal activity.)

Those written reports are not the final word; a higher-ranking immigration official (an independent “minister’s delegate”) renders the ultimate decision. In Muhammad’s case, two different delegates ignored the initial risk opinion and said he would not face risk if flown back to Pakistan—and both times, the Federal Court overturned that conclusion and sent the file back for reconsideration, postponing his removal.

The most recent court ruling was issued May 9, criticizing the latest delegate’s “unsupportable inferences” and “unreasonable” conclusion. Madam Justice Cecily Strickland even went so far as to openly wonder, after all that’s transpired, “whether there is, in fact, sufficient evidence to support a finding that the applicant is not at risk.”

A third minister’s delegate is now conducting yet another risk assessment. How long that will take isn’t clear. What is certain is that CBSA—after fighting for nearly three years to keep Muhammad behind bars, at considerable public cost, until his flight home—had a sudden change of heart, agreeing at a May 23 detention review to allow his release while the process unfolds. Conducted by the Immigration and Refugee Board (IRB), the detention review was not a public proceeding, and a CBSA spokeswoman said it would be inappropriate to discuss an ongoing case.

“What we can tell you is that the CBSA is committed to the safety and security of Canadians,” Esme Bailey wrote in an email to Maclean’s. “It is important to note that the ‘Wanted by the CBSA program’ was developed to seek assistance from the public in locating individuals who are inadmissible to Canada and are subject to an immigration warrant. It was not developed to maintain detention. Detaining someone is a serious issue. Immigration legislation specifies the grounds for detention, which include: flight risk, danger to the public, and uncertain identity. The CBSA always considers alternatives and recommends release on conditions where possible. Before making a recommendation to the Immigration and Refugee Board (IRB) on whether detention should be maintained or the person released, the CBSA carefully assesses the situation, which may vary from one detention review to the other.”

Clearly, last month’s Federal Court ruling was a major turning point. The judge herself suggested Muhammad may indeed prove impossible to deport—and by allowing such a high-profile prisoner to leave his jail cell, the federal government appears to be conceding that possibility.

The border service says Muhammad is just the third person featured on the Wanted list to be freed by the IRB, pending deportation. CBSA will not disclose the names of the other two men, and the IRB is still assessing whether it can publicize information from either case.

Although the Wanted list generated weeks’ worth of positive press after it was launched—and remains “a continued source of pride,” according to the agency’s vice-president of operations—the program has endured a difficult few months. In December, the federal privacy commissioner scolded the agency for its “potentially misleading” use of the term “war criminal,” noting that nobody on the website was ever charged with a war crime, let alone convicted. (They were declared inadmissible to Canada, under a much lower burden of proof, by the IRB.) A few weeks later, Maclean’s actually tracked down one of the “missing” men, raising more troubling questions about just how hard authorities are searching. (Asked why the magazine managed to locate Dragan Djuric when the agency could not, CBSA responded by promptly removing his headshot from the website and refusing comment.)

Where is Arshad Muhammad? Like anyone with a pending pre-removal risk assessment, his IRB detention review was conducted behind closed doors, and the details of his release conditions are confidential. Contacted by Maclean’s, his lawyer, Lorne Waldman, said he couldn’t talk about the case without his client’s permission.

But the 45-year-old Muhammad is no doubt under the watchful eye of at least one surety, who would have posted a hefty amount of money to secure his freedom. One potential bondsman, who submitted a sworn affidavit in an earlier proceeding, described Muhammad as a “very jolly” and “trustworthy” friend who helped his family settle in Canada when they first moved from Pakistan in 2010—while Muhammad was still evading federal authorities.

“I have complete faith and trust that Arshad would comply with any conditions ordered on him if I were the bondsperson in his case,” wrote the potential surety, now a Mississauga real estate agent. “He would never do anything to break the bond we have together.”