Inside the fight of Jack Layton’s life

His confidants and caucus colleagues recount the difficult days before and after his shocking announcement

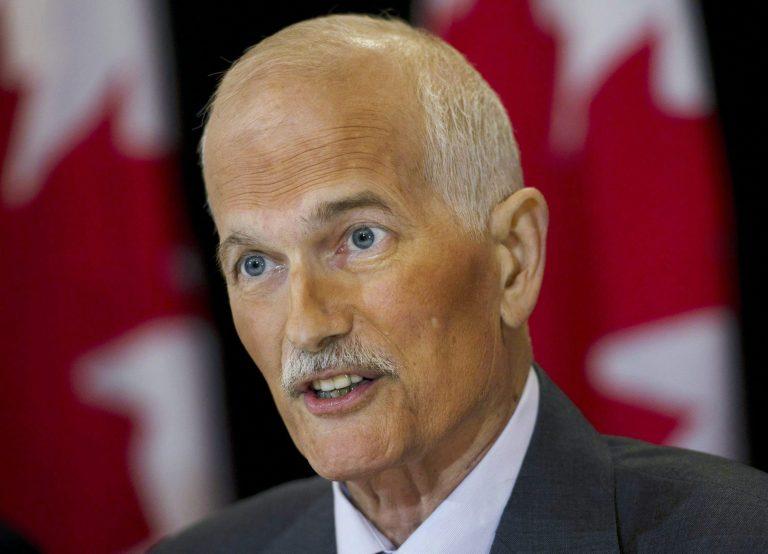

NDP Leader Jack Layton speaks at a new conference in Toronto on Monday, July 25, 2011. Layton will not attend a special NDP caucus retreat to plot strategy for September’s resumption of Parliament. (Nathan Denette/CP)

Share

Jack Layton died after a months-long battle with cancer in the early morning hours of August 22, 2011. He was 61. Below is Maclean’s cover story on the charismatic NDP leader, originally published on August 4, 2011. To read Maclean’s definitive profile of Jack Layton’s life in politics, click here.

He had started complaining of pain and stiffness in late June. He was perspiring a lot, and found it hard to stand for long periods of time. His chief of staff, Anne McGrath, who first worked with Jack Layton when he ran for the NDP leadership nine years ago, thought maybe he’d over-compensated for his surgically repaired left hip and injured the right one. She wanted him to take the summer off anyway. It would have been a deserved respite after a remarkable 18 months that began with a diagnosis of prostate cancer and climaxed with him hobbling to an unprecedented election result.

Tests were scheduled. But then he also started losing weight. McGrath prepared herself to find out what was happening on July 25, when a significant test was to take place, but that test was moved up five days. With those results came a diagnosis and on the evening of Wednesday, July 20, two days after his 61st birthday, Layton called McGrath to tell her it was cancer. “He’s so upbeat,” she says. “He really is. It’s so funny. I don’t get it sometimes myself.”

He told her to tell him that she was going to keep working. “ ‘We started this journey together…and look at how far we’ve come and look what we’ve done,’ ” she recalls him saying. “And he starts going through the things that we’ve been through and everything. He says, ‘And we’ve got more to do.’ He was talking to me about fundraising, about increasing the party’s membership. This is on Wednesday night, you know?”

He was not unmoved by the situation he now found himself in, but he was not shaken from the focus that sometimes seems to be all-encompassing. “He was upset and I could tell that there were tears,” McGrath says. “But again, he’s just very determined.” Here Jack Layton began the latest fight of his life: confronting it, McGrath says, as if it were a political campaign. “He’s the same with his health situation as he is with the party. It’s like, ‘I want the team together, I want to plan, it won’t be acceptable if it’s not this and that and the other thing.’

“He knows,” she says later, “he’s got a big fight on his hands.”

He had finished the spring campaign feeling fine. Doctors operated on his left hip in early March, just three weeks before the writs were dropped: a small fracture of unknown origin had worsened to the point that it required intervention. He not only managed the constant, cross-country motion of a national tour, but improved as the campaign progressed. On the penultimate night, as the NDP plane made its final trip, the reporters seated near the back turned festive and Layton joined in the party, even dancing a little to Aretha Franklin’s Respect.

The House of Commons reconvened on June 2, and Layton began to settle into his new role as leader of the Opposition. But around the third week of that month, he acknowledged feeling sore. He was scheduled to participate in Montreal’s Saint-Jean-Baptiste Day parade on June 24, but confided to his press secretary, Karl Bélanger, that he didn’t think he would be able to walk the route. It would become a moot concern when the NDP decided to filibuster Bill C-6, the government’s back-to-work legislation for Canada Post.

Whatever pain he was feeling, Layton stood and spoke for nearly an hour to launch that filibuster on the evening of June 23. However tired he was, he still sat after a vote and chatted with the Prime Minister for a few moments as the clock later approached 1 a.m. on the morning of June 25. But as the filibuster neared an end that Saturday, he told Thomas Mulcair, one of his deputy leaders and the opposition House leader, that it would be better if someone else handled one of the NDP’s final interventions.

After the filibuster ended, Layton returned to his home in Toronto. He was back in Ottawa a couple of days later to attend the spring garden party for members of the press gallery at Stornoway. “He was not feeling great,” McGrath says of that evening; indeed, it would later be noted that he had remained seated for most of his time there. The following weekend, he participated in Toronto’s Pride parade, seated in a rickshaw beside his wife, and fellow New Democrat, Olivia Chow. McGrath says it was “a bit of a struggle,” but Layton insisted he attend.

Two days later—on July 5—he attended a celebration thrown in his honour by members of the Chinese community in his riding: they wanted to congratulate him on the NDP’s election result. He stood at the door of the restaurant and greeted each guest, then later stood and spoke to the crowd for a half hour, Chow standing beside him to translate. He stayed at the party until 10:45 p.m. And if he was at all struggling, it was not apparent when Joe Comartin, the NDP’s justice critic and deputy House leader, spoke to him by phone a few days after that to discuss the parliamentary session just passed. Layton’s voice was strong and he seemed full of energy. They discussed plans for August and September.

Less than two weeks after speaking to Comartin, Layton learned he was once again faced with cancer. “It just seemed so unfair,” McGrath says of her worry before the final diagnosis, “to have gone through all of that before, and to have come through this really historic election and to have done so well, and then for this to happen.” On July 21, the day after Layton had called to tell her the news, McGrath summoned Bélanger to a meeting in her Parliament Hill office. She explained the situation to him and then called Layton. Here Bélanger first heard the hoarse voice with which Layton would soon address the country. Layton apologized for not being there to tell Bélanger in person.

That first day after the diagnosis, McGrath moved to inform the senior members of Layton’s staff—including Bélanger, principal secretary Brad Lavigne and director of communications Kathleen Monk—who needed to know in order to prepare for a public announcement. “It was not the news that I wanted to hear, but obviously it was the news that we had,” says Lavigne. “You plan for all of the various options that may come down to you. That is just the nature of what we do for a living. When we got the results and the leader had informed us of the decision that he wanted to make, we then needed to put into place the game plan. It’s Plan B, really. We had to implement Plan B.”

On the morning of July 23, McGrath travelled to Toronto to see Layton. She had asked Nycole Turmel to call her and that evening Turmel phoned. Turmel thought they were going to discuss strategy for the fall. McGrath handed the phone to Layton, who explained that he had cancer and that he wanted Turmel to take his place for the next two months. “When Mr. Layton talked to me I was in a state of shock,” Turmel says. “He wanted to recommend me as interim chief of the party. I asked him how it worked and he explained the process. And I said to him, ‘Mr. Layton, I will do what I have to do. If you really want me to do this, I’ll do it.’ But I had a lot of grief and I told him that.”

Turmel would be portrayed as a surprising pick, but McGrath describes her as an ideal candidate. She is a bilingual francophone from Quebec—a province that elected more than half of the NDP caucus—with experience running a national organization (from 2000 to 2006 she was president of the Public Service Alliance of Canada). Though a rookie MP, the 68-year-old is a veteran of both the labour and women’s movements, and was once an associate president in the party. “Because she’s been a leader in an organization, she knows that leadership is about listening and consulting, but it’s also about making decisions,” McGrath says. Turmel had also already been unanimously approved by her fellow NDP MPs to serve as caucus chair. (This week, Turmel’s ties to Quebec sovereignists—including the fact she once held a Bloc Québécois membership card—would present the first major test for the party in Layton’s absence. In response, Turmel said she joined the Bloc to support a friend—former Bloc MP Carole Lavallée—but that she never supported the party’s pursuit of sovereignty.)

When Layton handed the phone back to McGrath, she apologized to Turmel for having to ask this of her. Turmel says she barely hesitated. “When he asked me I considered it for about two seconds, because I saw that it was very important to him,” she says.

On Sunday, July 24, McGrath, Monk and party president Brian Topp went to Layton’s home to discuss the next day’s announcement. At one point, McGrath had assured Layton that he didn’t have to do it—that there were other options and he didn’t necessarily have to go before the cameras and explain himself to the country—but Layton wanted to deliver the statement himself. “I think it was important, and it was important for him, that if he felt that he could do the announcement that he should do the announcement,” Lavigne says, “that the words come from his own voice. The people of Canada deserved to hear it from him.”

Lavigne had left on a previously scheduled vacation to British Columbia and, working with text prepared by Layton and Chow, he sat at a picnic table outside his brother’s cottage near Cultus Lake that morning to work out a draft of Layton’s statement. The group at Layton’s home then spent the day going over what the NDP leader would say. The statement would begin straightforward and explanatory. His battle with prostate cancer was “going very well,” but he now had a “new, non-prostate cancer” that would require further treatment. He would be taking a leave of absence and he recommended Turmel take his place in the interim. With this outlined, Layton would conclude on a note of both optimism and determination, an appeal to lofty ideals and a reminder of political focus. “We will replace the Conservative government, a few short years from now,” he said. “And we will work with Canadians to build the country of our hopes. Of our dreams. Of our optimism. Of our determination. Of our values. Of our love.”

This was very personal. “Those were his words,” says Lavigne, another veteran of Layton’s 2002 leadership campaign. “That whole sequence of building that kind of Canada: it was his and it was very important to him that those exact words be in that statement.” The commitment to a political goal spoke, Lavigne says, to Layton’s entire purpose as a leader. “Those words are important not only because it illustrates how focused he and his team are, but it’s also a rallying cry to the supporters and to non-Conservatives throughout the country,” he says. “ ‘Look, I may have a second round of cancer and I may be taking some time off to fight, but let’s not lose track here or lose sight of what we’re in this for. And that is to build a better country and the way we do that is by defeating this Conservative government.’ ”

On Monday, before the announcement, Layton made phone calls to four senior members of his caucus: deputy leaders Mulcair and Libby Davies, deputy caucus chair Peter Julien and Opposition whip Chris Charlton. Davies missed Layton’s call, but heard his weak voice in his message and knew something was wrong. When she called him back, he took the opportunity to practise his statement with her. “He goes, ‘I need to keep saying this, I need to practise, I need to get it right,’ ” Davies recalls. Meeting at the downtown Toronto hotel beforehand, Layton told Bélanger, who organized Layton’s first news conference as NDP leader in January 2003 and has been with him ever since, that he wasn’t sure about his voice. “Well,” Bélanger replied, “some would argue it sounds sexy, sir.” Layton laughed.

Around noon, a notice went out to members of the press gallery that the NDP leader would be making an announcement and a message was also sent to the NDP caucus. Fifteen minutes before Layton walked into the news conference, Lavigne gathered those NDP MPs and staff members who were in Ottawa to watch as their leader told the country.

News of Layton’s prostate cancer had leaked 20 minutes before his announcement in February 2010. This time, Bélanger notes, the news did not leak until seven minutes before.

After he had delivered his statement, Layton ceded the stage to Topp and exited. In a nearby room, joined by his son, Toronto city Coun. Mike Layton, he watched some of the news coverage. He felt the announcement had gone well. Quebec Premier Jean Charest called to wish him well (on important occasions, Charest has typically been the first to call Layton). Later that afternoon, the Prime Minister phoned. “We are all heartened by Jack’s strength and tireless determination, which with Mr. Layton will never be in short supply,” Stephen Harper said in a public statement released by his office.

The rest of his MPs heard from him two days later, at a meeting to formally endorse an interim leader. Layton addressed the caucus via audio link, encouraging them to continue with the work of building the party. With a video link set up so that he could watch the proceedings from his home in Toronto, MPs took turns standing to speak, sharing stories and passing on messages from constituents. It was, by all accounts, an emotional few hours, with tears and laughter. “It’s an analogy that people have used and it’s an apt one: it was like a family affair,” says Paul Dewar, the New Democrat for Ottawa-Centre. Despite dozens of new members, the NDP caucus is said to be a united one, brought together in part by the experience of June’s filibuster. “In some respects, the government did us a favour by doing the back-to-work legislation,” Comartin says. That caucus now takes on a “mantle of responsibility,” as Comartin puts it. “We were going to have to show ourselves as a party and to show that it wasn’t absolutely about Jack,” Dewar says.

Reporters have not been told the details of Layton’s condition, but neither—with the obvious exception of Chow—have NDP MPs. It is unclear even how many of his senior aides are fully aware of what Layton is dealing with. In lieu of specific information, any number of explanations are possible. According to Danny Vesprini, a radiation oncologist at the Odette Cancer Centre at Sunnybrook Hospital and professor at the University of Toronto, “no definitive conclusion can be drawn” about Layton’s prognosis from his announcement. (Princess Margaret Hospital in Toronto, where doctors have been treating Layton since his prostate cancer diagnosis, released a statement explaining that “new tumours were discovered which appear to be unrelated to the original cancer and Mr. Layton is now being treated for this cancer.”) Vesprini, who does not know the particulars of Layton’s case, acknowledges the change in the NDP leader’s appearance. “He looked sick. Unfortunately it can happen over a relatively short period of time. He’s a skinny guy, so when you’re already skinny and you lose 10 lb., you look bad. So it’s relative. But in his situation, he does look very thin. It’s unclear whether that’s because of the disease, but everyone is thinking it, and the main concern is it’s because of his health.”

But Vesprini is cautiously optimistic that Layton will be back in Ottawa when Parliament resumes. “The reality is that there would be a lot of people in that scenario that may not be able to go back to work in September,” he says. “But the truth is that I have men in my practice who have looked as sick or sicker when I first met them because they had cancer that spread all over their bones, and three or four years later they’re fine, golfing and doing things. It all depends on what it is, and whether it responds to treatment.” The decision to mark Sept. 19—when the House of Commons is scheduled to resume sitting—as Layton’s expected return was his own. “He likes deadlines, plans,” McGrath says. “It’s part of his personality.”

Last weekend, McGrath and Topp visited Layton at his home in Toronto. His voice sounded stronger and he was able to walk them to the door as they left, without the assistance of a cane (he threatened to dance, McGrath says, much to the concern of Chow). Two baskets of DVDs put together by the actor-director Sarah Polley had arrived—she asked supporters in the arts community to suggest picks—and McGrath had other gifts from New Democrat MPs. He was still keeping in touch with McGrath about the party and they discussed various matters, including the American debt crisis.

In his absence, his team aims to carry on the work of preparing for the fall and building for an election four years hence. “If it’s fair enough to say that you can be both devastated and optimistic at the same time, that’s probably what the mood is,” McGrath says. “I’m very shocked, very sad, devastated and very hopeful and determined to do what needs to be done—because that’s what this team has always been about.”

Indeed, the feelings seem both mixed and resolute: tied to a leader who, as McGrath says, can be caring and emotional, but disciplined and determined. “There’s sadness and there’s anger and there’s frustration,” says Bélanger. “But then again there’s this friggin’ guy who comes in and delivers this message of hope and optimism. The same message that kept me around for eight years and a half.”

Layton’s only public comment since announcing his cancer came in the form of a tweet posted two hours after he finished his statement. “Your support and well wishes are so appreciated. Thank you,” it read. “I will fight this–and beat it.”