Is Canada ready to deal with stoned drivers?

As Canada prepares to legalize marijuana, it is totally unprepared to deal with the most dangerous side effect

(Photograph by Nathan Cyprys)

Share

Tyler Manaigre had been smoking up—that much was quickly established. He admitted to the RCMP corporal who stopped him near Steinbach, Man., that he’d had “just a little bit” of pot that night, assuring Corp. Terry Sundell that it was “like, way earlier.” But the tell-tale signs lay around the back seat of his 2012 Ford Focus: Ziploc bags bearing pot-leaf motifs; a beer can bearing a burn mark and crumpled in a fashion Sundell later described as “consistent with use as a makeshift pipe.”

Manaigre, 25, had been driving cautiously that cold November night. But it turns out that a guy doing 20 km/h under the speed limit on a preacher-straight stretch of highway at 1:49 a.m. is more peculiar to Mountie eyes than someone blowing by at top speed. So, notwithstanding Manaigre’s otherwise flawless driving, Sundell flicked on the rolling lights and pulled him over.

What followed is an object lesson in why precious few Canadians are convicted of cannabis-impaired driving. Sundell is what police call a drug-recognition expert (DRE) — an officer specially trained to detect and identify substances a driver has taken, thus establishing legal grounds to demand a urine or blood sample. He asked Manaigre to perform a standard roadside sobriety test — nose touches, line-walking and the like — and thought the young man performed them poorly. So he arrested Manaigre and drove him to the Steinbach detachment for the more comprehensive evaluation Sundell had just weeks earlier learned to administer.

There, Manaigre, who bears passing resemblance to the actor Jonah Hill, gamely went through a battery of eye inspections, heart-rate checks, walk-and-turn tests and demands to stand on one leg while counting down 30 seconds. As the clock ticked past 3 a.m., he started to struggle. During the one-leg test, he got to “14 Mississippis” before wobbling and putting his right foot down. He couldn’t cross his eyes on request. When asked to stand on his right leg, he had to put his left foot down three times to maintain his balance.

These missteps and others convinced Sundell he had grounds to demand a urine sample, after which Manaigre came clean: in a statement to police, he admitted to smoking a little less than a half-gram of marijuana, the equivalent of two regular-sized joints, between 12:30 and 1 a.m. He’d been using a bong at his sister’s house, he said, and the buzz had been “pretty good.” Only in the back of Sundell’s police car had it worn off, he said, and even at the detachment he felt a little bit tipsy. So Sundell swore out a charge of impaired driving by drugs — an accusation buttressed a few days later when Manaigre’s urine test came back positive for cannabis. To unschooled eyes, Manaigre looked to be in trouble.

Yet after hearing the evidence at a trial last year, Provincial Court Judge Cynthia Devine let him off. “I am satisfied that he consumed marijuana,” she said in a decision issued in December. “I am even satisfied that he felt the effects at some point. But I am not satisfied beyond a reasonable doubt that his ability to drive was impaired.” One problem with the Crown’s case: Manaigre’s driving didn’t seem all that bad. Sure he was travelling under the speed limit, the judge noted, but it wasn’t like he was all over the road. As for his poor performance on Sundell’s physical tests, the judge described the exercises as seemingly “complicated and difficult,” adding wryly: “I suspect they might well challenge the balance of many completely sober people.”

Related: Canada’s real marijuana problem

Here, then, is Canada’s state of readiness mere months before its era of lawfully accessible weed is supposed to begin. A man who admits to smoking marijuana an hour before driving—who shows outward signs of doing so; who tests positive for the drug; who admits he’s feeling tipsy; who has difficulty performing the physical tests designed to detect drug use — is not necessarily breaking the law.

To pot users, this might sound like a triumph of legal discretion. Cannabis is not booze, they point out. Its effects can vary from person to person, and it acts differently on the brain over time. But to safety advocates, the uncertainty surrounding cases like Manaigre’s shows how unprepared Canada is for the greatest hazard to public safety that legalization implies. More stoned drivers on the roads, they warn, will be a near-certain side effect of the Trudeau government’s plan — a hypothesis founded on tragic experience whenever liquor sales have been liberalized to make booze more available. Will the costs of legalization be measured in human lives?

Already, roadside surveys suggest more people drive under the influence of drugs than alcohol, with cannabis by far the most common. In a 2014 survey, 10.2 per cent of randomly screened drivers in Ontario tested positive for at least one drug other than alcohol, compared to four per cent for alcohol alone (many had used both). Of those who took drugs, 43.6 per cent were positive for cannabis. In 2012, fully 40 per cent of those killed in car accidents in Canada tested positive for recent use of drugs—nearly half of them for cannabis—versus the 35.6 per cent who’d been drinking.

Bringing high drivers to justice has proven tough, though, because marijuana defies the measures developed over the decades to combat drunk driving. Unlike alcohol, THC content in the blood can’t yet be measured with a cheap and reliable breath test. While urine tests can reveal THC, they leave open the question of how recently it was smoked (the metabolites detected linger up to 12 hours after the person was feeling any effect from the drug). That leaves police with the costly, invasive and legally fraught task of obtaining blood samples if they want an accurate picture of how high the person was, and when the effect of the drug was strongest. Even if those samples come back positive, there’s no guarantee of conviction, because Canada has no hard-and-fast limit of THC content in drivers’ blood like it does for alcohol. It doesn’t even have scientific consensus regarding how much is too much.

In the absence of a blood-THC limit, the Crown must prove the drug has impaired the person’s ability to drive. For that, it relies heavily on the evidence of DREs like Sundell, who had completed a two-week course in Jacksonville, Fla., just weeks before he pulled Manaigre over (a request to interview Sundell went unreturned, while Manaigre declined comment through his lawyer). Their 12-step examinations are time-consuming, involving more than 100 different pieces of physical and psychological information. And like everything else in the impaired-driving enforcement scheme, they are under attack.

Next week, the Supreme Court of Canada will hear the appeal of accused drugged-driver Carson Bingley, who in 2009 drove the wrong way up an Ottawa street and hit another car in a parking lot. Among the questions now before the court: whether a special hearing must be held at every trial before DREs’ testimony can be admitted—and whether, legally speaking, they are “experts” at all. Anxious to preserve officers from courtroom grillings on the science underlying their work, Crown lawyers suggest the courts instead treat DRE testimony as “lay opinion,” like that of any person reading signs of intoxication.

Related: Canadian doctors want feds to regulate THC levels in marijuana

Small wonder, then, so few Canadians are sent up for driving high. Last year, police charged just 1,575 people with drug-impaired operation of a vehicle, vessel or aircraft, compared to 50,853 for suspected drinking and driving. Statistics Canada doesn’t break out the conviction rate of drugged drivers. But the charge count seems astonishingly low for illicit behaviour known to be so prevalent. Part of the problem, says Neil Dubord, chief of police in Delta, B.C., is that relatively few resources go to keeping high drivers off the road. His 200-member force, for example, has just one DRE, and training more would come at a high price: two weeks off duty per officer, plus another week or two for field certification, after which he or she must be accredited by the International Association of Chiefs of Police. Total estimated cost: $17,000.

The result can be seen on a typical Friday night in Delta, a fast-growing city in B.C.’s Lower Mainland where pot use is commonplace. “I may have 15 or 18 officers on the road,” says Dubord, whose role as chair of the traffic safety committee for the B.C. Association of Chiefs of Police has landed him at the centre of the stoned-driving dilemma. “They may do 20 or 25 vehicle stops. They may meet six or seven people, say after midnight, who have too much on board [their bodies] when it comes to marijuana, prescription or other drugs. But unless those people are showing significant signs of impairment, I guarantee you there’ll be four or five who walk away without any consequence.”

If Dubord sounds worried, it’s because he and other cops are caught in a conundrum. Legalization may reflect Canadian society’s more enlightened attitude toward marijuana, and the limited dangers it poses. But widespread belief in the stuff’s essential harmlessness is blinding people to the menace it poses on the roads. In a recent survey of Canadians by the State Farm insurance company, fully 44 per cent of respondents said they didn’t believe that marijuana use affects their ability to drive safely, versus 42 per cent who said it does (14 per cent weren’t sure).

The difficulty police have detecting stoned driving doesn’t help. Screaming headlines about accidents caused by high motorists are rare, because many drug-impaired drivers are also drunk, and prosecuted as such. Young people, in particular, tend to doubt the dangers of drugged driving. Three years ago, researchers with the Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse were appalled to hear teenagers in focus groups claiming that smoking up actually made them drive better. “I get in the car [with my friends] and I’m, like, ‘Are you high?’ ” one girl in junior high school told them. “And they’re, like, ‘Yeah man.’ And they don’t crash. They just drive and, like, the more high you are, like, you focus.” Added a boy in senior high: “It started to make me more cautious.”

Such ideas are rooted not in denial but the peculiar effect THC has on people trying to do complex tasks. While drunk drivers lose awareness of their impaired state, many stoned drivers overestimate their level of impairment, according to a 2008 study of people across Canada in treatment for drug addiction. Driving under the speed limit counts among what the researchers described as “compensatory strategies,” often employed to avoid detection. In layman’s terms, high drivers get paranoid.

That makes them no less a menace. Trials performed in driving simulators have found that pot reduces drivers’ ability to stay in their lanes and manage their speed (the flip side of the slow-driver scenario: speeding is the most common reason drugged motorists get pulled over). High drivers also tend to obsess on one task—say, their following distance from cars ahead—while ignoring equally important factors such as the positions and speeds of the vehicles around them. That “compensatory” instinct gives them sloth-like reaction times: they take too long to decide to pass, or to brake for changing lights. In the 1980s, U.S. researchers reported that people on high dosages of pot were a lot more likely than sober drivers to crash into sudden obstacles.

All of these effects are more pronounced when weed is consumed in combination with alcohol, as is the case in an estimated 19 per cent of impaired cases. However nonchalant drugged drivers might be about the dangers, their representation among Canada’s highway dead is on the rise. Since 2000, the number of drivers fatally injured in accidents who tested positive for drugs has risen by about 14 per cent. These stats include stoned drivers who weren’t at fault. But long-time impaired-driving researchers are quick to point out that car crashes are the No. 1 cause of death related to cannabis. “People who overdose on pot aren’t going to die,” says Douglas Beirness, a senior research associate with the Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse. “Not unless they do something stupid — like get behind the wheel of a car.”

Certainly, the evidence of harm is strong enough that governments across the country are scrambling to ready themselves for the end of prohibition. As of this week, drivers in Ontario who fail a roadside sobriety test due to suspected drug use will face an immediate $180 fine and three-day licence suspension — a change made possible by provincial jurisdiction over highway and traffic law. The administrative penalty, which reflects those for suspected alcohol use, will rise to a seven-day suspension on second offence, and a 30-day loss of licence on third. Failing a DRE evaluation will yield a 90-day suspension.

Meantime, driving high has emerged as one of the most pressing issues confronting the Trudeau government’s federal task force on marijuana legalization, led by former Liberal justice minister Anne McLellan. If Canada is to limit blood-THC content like the one for alcohol, or allow police to test for drugs at the roadside, it will need amendments to the Criminal Code. A discussion paper recently released by the task force raises those possibilities, while safety advocates point to Colorado and Washington, which backstopped marijuana liberalization with blood-THC maximums for drivers of five nanograms per millilitre. To prove a driver is over the limit, police in those states must obtain special warrants against drivers who have failed roadside sobriety tests, then take them to the nearest police station, firehouse or hospital to draw blood samples.

Opinion is divided as to the wisdom of THC limits. Supporters include Dubord, the Delta, B.C., police chief, who believes they short-circuit pointless debate over whether some drivers drive well when they’re high. “I don’t just think it would help,” he says, “I think it’s critical.” But Beirness, the CCSA researcher, warns that any limit in Canada would face court challenges over when the THC level was measured, and whether it shows the person was above the limit when he was driving. In many cases, he notes, hours have passed by the time police get to the point of obtaining blood, which helps explain why 80 per cent of drivers arrested for suspected drugged driving test under five nanograms. “Everybody wants to do the same things for cannabis that we did for alcohol,” he concludes. “It’s not going to work.”

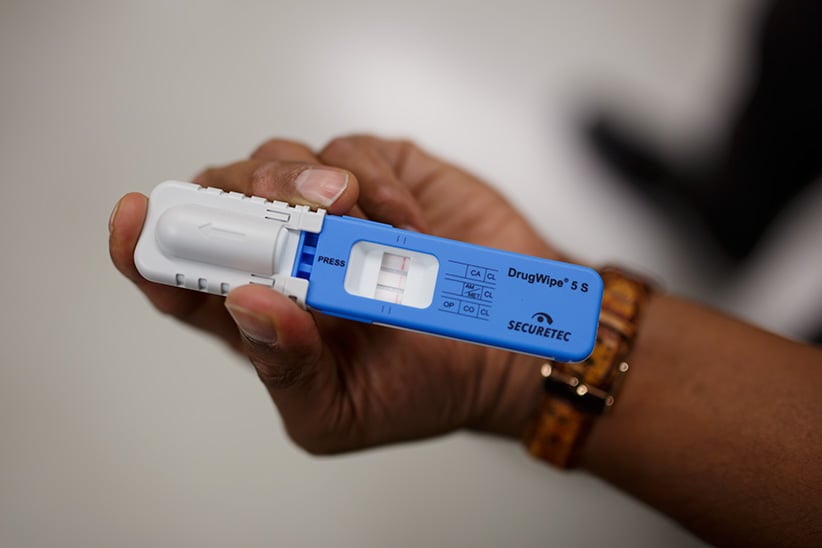

Chris wouldn’t risk piloting his skateboard right now, never mind driving a car. “I’m quite stoned,” the 29-year-old says matter-of-factly. “The situation I am in is . . . strange.” He’s gotten high at Maclean’s request, rolling joints from a packet of so-called “Strawberry Castle” obtained from a Toronto dispensary, and toking up at midday in a city park. Now puffy-eyed and talkative, the tech company employee (he asked that we not use his full name) says he wants to do his part to discourage stoned driving. But the point of this exercise is to try out a saliva testing kit meant to help cops identify drugged drivers at the roadside, within minutes of stopping them.

So, half an hour after he’s lit his second joint, Chris presents his tongue for a DrugWipe 5S, a German-made device which scans for the presence of cannabis, opiates, cocaine, amphetamine and methamphetamine. It’s not unlike a home pregnancy test. A finger-punch to a plastic bubble releases a chemical reagent, and within minutes two red lines appear on the cannabis strip, confirming that Chris has indeed partaken of the herb. DrugWipe shows positive when a person’s blood-THC level is at least 0.1 ng/ml—double the limit in Colorado and Washington. “If that means I shouldn’t drive in this condition,” says our subject, steadying himself on a picnic table, “I wholeheartedly concur.”

The speed with which he’s been tested is important, because unlike alcohol, cannabis’s action on the brain is short-lived. Studies show maximal effect from a single dose occurs 20-40 minutes after use, while impairment is over within 2.5 hours. That’s an enormous legal problem because, Beirness points out, it can take that much time to get a suspect driver to a police station to perform a drug-recognition test.

A reliable oral fluid test like DrugWipe could change that by establishing what lawyers refer to as “recent use.” Safety advocates liken them to the hand-held breath-alcohol detectors many police carry in their cars: they are not, on their own, evidence of intoxication, but rather grounds for further tests. With a change to the Criminal Code, goes the thinking, a positive result on DrugWipe could allow police to demand a blood test—or better yet, a second, more accurate saliva test based on more advanced technology. Those results, in turn, would stand up in court, eliminating the need for a DRE evaluation. But for the system to work, Parliament would have to adopt a specified blood-THC limit, eliminating any question of whether the person was impaired.

DrugWipe is one of three roadside saliva tests police are trying out with a view to having them approved by the time marijuana legalization takes effect next spring. Though Canadian regulators would require proof of their reliability before they could be approved, a lot of that heavy lifting has been done. DrugWipe, for one, is already being used in Germany and the U.K., notes Abe Verghis, regulatory affairs manager of Toronto-based Alcohol Countermeasure Systems, the device’s North American distributor. In lab testing, it has proven 100 per cent accurate, and in early roadside trials, it identified seven out of 10 drivers who had used cannabis. Finnish researchers reported false positives and negatives in 2011, but they acknowledged the device’s sensitivity has improved.

Related: Bill Blair: The former top cop in charge of Canada’s pot file

So whatever the pitfalls, Canada’s response to drugged driving is likely to look like that for drunk driving. In its submission to McLellan’s task force, Mothers Against Drunk Drivers (M.A.D.D.) has called on government to authorize both roadside testing of oral fluid and to set a blood-THC limit, the exact level to be based on scientific consensus. The group also argued that government could keep marijuana from the hands of young people, who are most likely to toke and drive, by setting the age to legally purchase marijuana at 21.

They are by no means unique ideas — Colorado and Washington adopted a 21-year age limit, the same as for liquor in those states. But the cost of enforcing them could dwarf that of detecting and prosecuting drunk drivers. While alcohol breathalyzers cost thousands up front, the price of a breath test falls once the machine’s been paid for, to little more than the eight cents for each driver’s sterile blow tube. One DrugWipe kit, by comparison, retails for about $40, taxes in, while a subsequent blood test would add much more, including the labour costs of a qualified medical professional to extract it.

That’s before defence lawyers start putting the new rules to a constitutional test. Robert Solomon, a Western University law professor who helped write M.A.D.D.’s submission, anticipates that any THC limit will be challenged as arbitrary, given cannabis’s varying effect on individuals, and continuing scientific debate as to what the limit should be. The response, he says, will be simple. “Abritrary? Yes, just like the speed limit is arbitrary. You might drive at 120 km/h way more safely than I do at 90, but try using that as a defence.”

Still, even to legal hawks, some clear lines in the sand would be an improvement. One flaw in the DRE model, says Michael Dyck, the Winnipeg lawyer who defended Manaigre, is that it can feed otherwise groundless suspicion on the part of the testing officer. “It’s confirmation bias,” he says. “The officer is already of the view this person is or could be under the influence of drugs. They’re looking for evidence that supports their belief, so they can lay a charge. They’re going to discount or discredit or give less weight to evidence that points away from their belief.”

Manaigre, Dyck says, presented just such a case. He showed no signs of swaying or disorientation through his long night at the police station. But nor is he a yoga master, notes the lawyer, so when the time came to stand on one foot, point the other forward while counting out seconds—all in the wee hours of the morning—he started to topple.

Perhaps, but the only thing cut and dried in the land of pot is the weed itself, and Manaigre surely regrets a few of the decisions he made that night—in particular, his choice to get behind the wheel after he’d been smoking up. If nothing else, he might steer clear of Steinbach, pop. 13,500, which bills itself as the Automobile City due to its surfeit of car dealerships. “It’s worth the trip!” proclaims a marketing slogan that for decades has persuaded car-shopping Winnipeggers to make the one-hour drive. When the era of lawfully obtainable pot takes hold, the merchants might wish to attach an asterisk of the sort commonly seen in car ads. “Offer does not apply to everyone,” the fine print could read, “nor to every kind of trip.”