Meet the great-great-great-great-granddaughters of Confederation

From a teen with a Céline Dion connection to a skiing daredevil, Meagan Campbell meets the descendants of Canada’s founders

Maya Price at Caesar’s Palace, where her father lives 18 weeks of the year. (Photograph by Emma McIntyre)

Share

The fan making Sir Charles Tupper big in Vegas

Maya Price is a 14-year-old with connections to Hollywood and historical heroes. Not only is she the great-great-great-great-great granddaughter of Sir Charles Tupper, former prime minister and founding father of Canada, but she is also the daughter of Céline Dion’s music director.

Once, in 2016, Price flew on Dion’s private plane, where she ate truffles and watermelon while being shuttled from a concert in Quebec City to her hometown of Montreal. Twice before that, Price hung out with the singer on the job, backstage at a show in Las Vegas and in her recording studio in Montreal. “She was kind of, like, hyped,” Price says of Dion’s performance adrenalin in Vegas. So was the tween, who was 12 at the time, and got a tour of Dion’s wardrobe (she refrained from touching the rows of silver pumps). In the recording studio, the girl was asked for advice on a rendition of “Recovering.” “I was kind of, like, flattered,” says Price.

Maya’s father, Scott Price, arranges the music for Dion’s 29-part orchestra, conducting 15 strings, five brass instruments and three backup singers, while playing piano himself. “We did Jimmy Fallon. We did Ellen DeGeneres. All those things are cool,” says Scott, a graduate of the Royal Conservatory in Toronto who got the job with Dion in 2015 after composing for artists and television shows including Just for Laughs: Gags. He also now directs the music for some Cirque du Soleil performances.

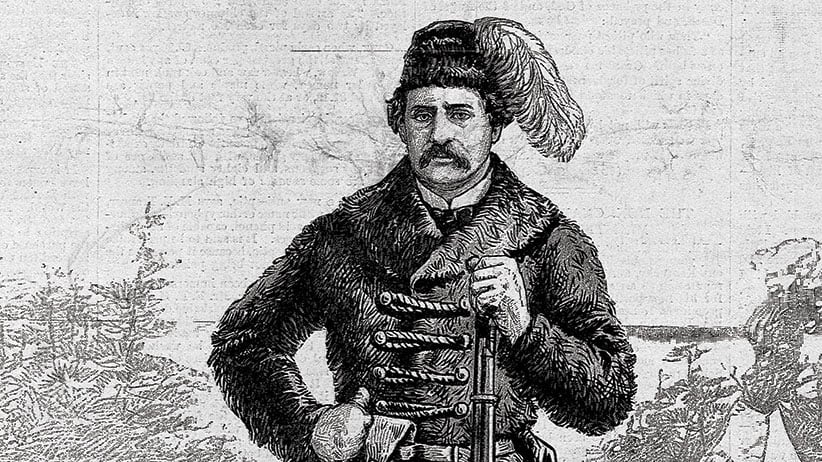

More bragging rights hang in Maya’s grandmother’s house: a photo of Tupper, who Maya recently discovered is her ancestor. “It’s as cool as my dad with Céline,” she says. Tupper flew on no private jet, signed no deals with the Bee Gees and never made it on The Ellen DeGeneres Show, but as premier of Nova Scotia, he launched the construction of the province’s railways, signed Confederation documents for Nova Scotia, served as prime minister for 10 weeks (before his Conservative party was voted out) subsidized public schools and protected French-language rights.

Maya’s Canadianness goes further. Her toy poodle is named Grizzly; she strictly distinguishes herself from Americans (“A lot of my friends are, like, traumatized by Trump”), and she points out, “I’m pretty girly, but I like to chill at a cottage.” Girly, surely: Price follows makeup artists on YouTube and carries a Louis Vuitton wallet; she also gets monthly manicures. “My nails are a bit tired of nail polish,” she says, explaining that she currently opts for fake acrylics.

Maya has pricey tastes. A private trainer visits her at her condo building in Montreal, and on a recent trip to Vegas, she dined on Kobe beef and crispy rice with tuna in the same restaurant as Miley Cyrus. Price has been to Florida and Milan. She’s done Corsica, London and Tokyo, where one of her two older sisters was working as a model. Back home, a typical day includes analyzing endoplasmic reticula at her private school and doing her custom training regime at her gym while singing along to “OMG” by Arash featuring Snoop Dogg.

She figures her destiny might be to study at McGill University like her sisters, aged 21 and 22, then get into entertainment law, medicine or music. She also likes math.

Her grandfather, “great” five times over, is also framed in a photo above her father’s piano, but the family focuses on its other Canadian icon. “Céline is my day-to-day existence,” says Scott, who says her celebrity is spreading. “It’s all over the bloody world. She’s like pop-music royalty.” Meanwhile, “Sir Charles Tupper is not as in-your-face all the time.”

The wee diplomat for Joey Smallwood

Josephine Smallwood cannot escape her name, not in St. John’s, not in China. When a tour guide called for her in a hotel on a recent trip overseas, the Canadians in the group swivelled their heads. “Suddenly you were some kind of princess, or on the other hand, you were some kind of little devil, just because of your name,” she says. “I was totally on this tour to see China and zone out and not talk about Newfoundland politics.”

Josephine, 67, is the eldest grandchild of Joey Smallwood, who led Newfoundland to join Canada in 1949. Her grandfather was controversial enough to need two bodyguards and carry a gun, adored by much of the province but detested by patriots who believed he sold them out. Born the year after the merger, Josephine grew up close to “Poppy,” and her Smallwood name has been forever a big deal.

At age six, Josephine was nearly orphaned. On Joey’s pig farm, where he built a home called Newfoundland House, a helicopter pilot was giving aerial views to her father, Ramsay, her mother, Florence, and her twin, Dorcas. Josephine was watching from a farmhouse window with her three siblings when the helicopter hit a power line and exploded. “The whole world stopped,” says Josephine. An uncle “leaped into an inferno” and pulled out her father, who was airlifted to a burn unit in Toronto and lay unconscious for nine days. Dorcas survived with burns. It was weeks before Josephine was told her mother had died. “We were just waiting for Mummy to be coming home.”

While her father recovered, Josephine spent time with Joey, whose chronic curiosity about the world fuelled his collection of 18,000 books, including anything that mentioned Newfoundland. On world travels, he would send home shipments of souvenirs, including a trunk containing gumdrop-shaped shoes and silk pantaloons. He would play with the grandchildren as they donned costumes, and at dinner he’d concoct wine-coloured juice. He doted on them with his wife’s record player in the background, except, as Josephine recalls, “when the news came on, it was, ‘Silence!’ ”

[widgets_on_pages id=98]

As premier, Joey told his constituents, “We are not a nation. We are a medium-sized municipality left far behind in the march of time.” Locals accused him of misusing funds—for example, to biannually change the tires on his Cadillac. Josephine’s cousin, Dale Fitzpatrick, recalls the people who marched into Joey’s office: “Everybody from Jean Chrétien to Sally Sue whose social services cheque was held up,” says Fitzpatrick. Even when Josephine was a girl, she was approached by people who either revered her or “wanted to take you to the guillotine.” She learned about the province osmotically, sleeping overnight in the “Newfoundland room” of Newfoundland House, staring at posters of Newfoundland.

Josephine received special privileges thanks to her grandfather. Joey convinced a retired principal to return to teaching at a schoolhouse near the children’s family farm west of St. John’s so they wouldn’t have to bus to school. When she was 11, Joey fast-tracked her visa so she could join him in England; Josephine drank her children’s wine in the company of military generals during the Six-Day War. “We were privy to whatever was on the go,” she says. “Our access was never denied.”

At boarding school, Josephine earned a red sash for sitting and walking with proper posture, and at a dairy bar in the summers, she earned money making milkshakes and sundaes. While her brother took over the family’s poultry farm, she studied history and English at Memorial University—“I was not really a chicken person per se”—and met her future husband in St. John’s. Though the couple later divorced, they had three children, beginning with Natasha. Josephine named her daughter for a character in a Leo Tolstoy book. Although her neighbours initially struggled to pronounce it, they wanted to be part of Joey’s legacy—he died in 1991 following a stroke—and after the birth of his great-granddaughter, Josephine recalls, “we had lots of little Natashas here in Newfoundland.”

A defender of the legacy of Louis Riel

Ginette Abraham wanted to be a funeral director. “I have always thought that would be a good profession,” she says, although the required courses were too expensive. “I’m not afraid of the dead. I’m not afraid of dying.”

From Grand Point, Man., and from the family of Louis Riel, Abraham shares some of the fearlessness of the rebel who was exiled and hanged for protecting the rights of Metis and French Canadians. Riel was executed at age 41 and had no grandchildren, but Abraham is “very, very, very” proud to be his great-great-niece.

Abraham was born Metis, French and poor. In a household of 12 children, her mother insisted they watch French television to preserve the language. With her father working in a grocery store, she wore used clothes with the exception of a beloved pair of bell-bottoms that were a 12th-birthday gift. Her teenage brother was killed on his bicycle by a drunk driver, and she says they got sparse compensation because of their race, but her mother made them proud to be Indigenous. “She didn’t teach us about being Metis,” says Abraham. “She taught us about being human.”

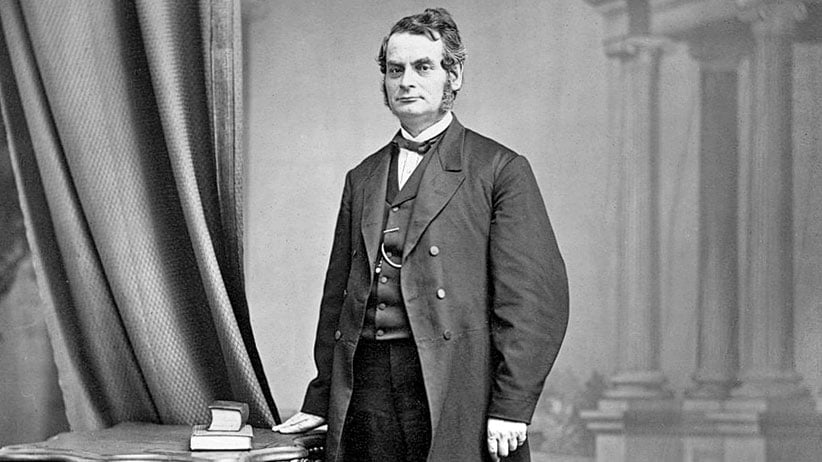

Integrity runs in the family. Before Manitoba became a province, the Canadians were poised to take over Riel’s homeland of the Red River Settlement. Riel formed a government for the Metis, and when Canadian armed forces arrived, his people captured them and executed one soldier. Riel went into voluntary exile in the United States, but returned to Canada to enter federal politics. In a later protest, Abraham recalls, “he stepped on the surveyor’s chain and said, ‘I’m sorry, there’s been a mistake. This is the land of the Metis.’ ”

While defending Indigenous people in Saskatchewan in 1885, he was charged with treason, and, to his anger, his lawyer tried to invoke the defence of insanity. Since Riel couldn’t afford to hire a different counsel, he made an eloquent speech in court, proving himself sane and leading him to be hanged.

“He’s part of everything that happens in my life,” says Abraham. In elementary school, nuns bullied her for her background, even though she attended Roman Catholic mass, dutifully rehearsing for her First Communion by practising eating a wafer without crunching and without letting it stick to the roof of her mouth. In Grade 6, a teacher introduced Riel to the class as a traitor, but Abraham raised her hand to point out that there’d been a mistake.

Abraham was also unafraid of Manitoba winters. Her childhood home was insulated with sawdust; the place was so cold that she thought her family never got sick because germs couldn’t survive. Wearing long johns beneath her bell-bottoms, she would skate on lakes with friends, who would line up single file and try to hang on to each other as the leader skated erratically to fling them off in a game of “crack the whip.”

After high school, without money to move outside Manitoba to become a funeral director, she studied social work in Winnipeg. She worked at an arts council, taking in free ballet and opera, and at a union for female garment makers, before becoming a professor at the University of Manitoba. She met her husband through friends and, though they later divorced, had two daughters, one of them a born rebel. “My youngest was an omnipotent child,” Abraham says. When the girl was three, the family wasn’t listening to her over a meal, so the toddler pounded on the table and declared, “I demand respect!”

Today, Abraham demands that her great-great-uncle be exonerated, and that Indigenous rights be upheld. When her mother died, she postponed the funeral for two weeks to Feb. 19—Louis Riel Day. She invited Metis drummers and brought a shawl, given to her mother at an elders’ ceremony, to drape over the casket. Abraham says, “You could tell that funeral was done by me.”

A caretaker for Samuel Tilley

The statue of Sir Samuel Leonard Tilley—pharmacist, knight and founding father of Canada—should not be covered in bird poop. Marianna Pangman—his descendant and the founder of a landscaping business—would like to give him a cleaning. “I see Great-Grandfather in Saint John, New Brunswick, looking down on the world,” she says. “I look at him every so often and think, ‘He needs a clean.’ ” She hasn’t taken action yet, so “he’s getting quite green from all the patina dripping off him.”

Pangman, 80, is a dutiful great-great-great-granddaughter. She doesn’t just worry about Tilley’s statue but has also been loyal to the country he helped establish. Although Pangman was born in England, she was repeatedly drawn to Canada and finally settled in Toronto, this year celebrating Canada Day with particular Tilley-centric pride.

Canadian and British, Pangman identifies as “half and hawf.” She was born in the U.K. but soon moved to New Brunswick to escape the Second World War, and she wandered back and forth for decades before settling in Toronto. When she was a child, her father served overseas but returned to the Maritimes in 1945—“How he ever managed to make it from North Africa to Saint John, New Brunswick, is beyond me,” she says. She returned to Sussex in the U.K. at age 8. Pangman’s childhood beyond boarding school was highlighted by picnics and polo. As a teenager, she lived in Paris to learn French. She has never forgotten the phrase “Je suis pleine”—“I am pregnant”—which she mistakenly announced in a restaurant when trying to say “I am full” after eating her first ever bowl of yogourt.

Bilingual, she missed Canada and circled back to it, learning to square dance in Cape Breton. She smoked her first cigarette in a parking lot in Baddeck, N.S. “I think I coughed and spluttered my way through one,” she says. At age 20, she met a man named Henry while visiting Saint Andrews, N.B. They dated for a few months before Henry left for Australia. Little did Pangman know that Henry had an identical twin with whom she would one day fall in love.

Pond-hopping once more, she moved back to England. “Big mistake. I wanted back to Canada,” she says. She lived in Montreal and Toronto and often visited New Brunswick, where she once found Tilley’s statue vandalized. Tilley was a prohibitionist, and in the early 2000s, Pangman noticed that miscreants had planted a beer bottle in his arms at night. “So I called the mayor,” she says.

Other Tilleys, too, are proud. Pangman’s niece owns Tilley’s Bible, which he was supposedly reading when he came up with “the Dominion of Canada” as the country’s original name. Tilley served as minister of customs under John A. Macdonald, who gave each of his ministers one of his dining-room chairs when he moved out of his house. Pangman’s great-nephew, a 20-year-old university student in New Brunswick, has that chair in the living room of his student apartment. “Do not sit on it,” he tells his friends.

Pangman never entered politics, but she shares her ancestor’s business sense. Tilley was originally a pharmacist, and he founded a shop called Cheap Drug Store! ( he didn’t get proper treatment when he cut his foot in 1896, and many people believe he died of blood poisoning, though his death certificate states the cause of death was Diabetes). In her 20s, Pangman worked in Toronto at the jewelry store Birks, selling “all the nice baubles.” On one Valentine’s Day, a customer told a woeful story of being short on cash for his sweetheart. He then hopped the counter, snatched a purse and darted out of the store, only to be chased down Bloor Street by Pangman’s manager in dress shoes.

Later, at a dinner party, Pangman met a sweetheart of her own, Ted, who worked in gold mining, and who turned out to be the twin of Henry. Henry had become a banker with Manulife, and gladly reunited as friends with Pangman. She and Ted married; she has one daughter, and Pangman went on to start a landscaping company. She and Ted spent many Julys sailing on Lake Ontario, but this year, she will visit New Brunswick for Canada Day.

In accordance with her granddaughterly duty, she has noticed another blemish on Tilley’s statue. The plaque is chipped. “I need to do something about it,” she says, “and I will—this summer.”

John Mercer Johnson’s German connection

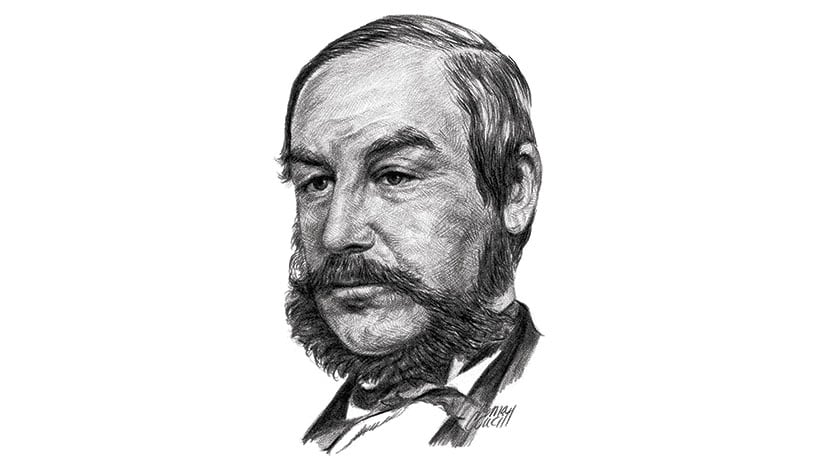

In a yellow brick house in Münster, Germany, next to finger paintings of a family of four, there hangs a photo of Canadian founding father John Mercer Johnson, a lawyer and celebrated orator. The house belongs to Annica Guhr, Johnson’s continent-hopping great-great-great-great-granddaughter.

Guhr took her husband’s surname, but she maintains familial pride. An expat of 12 years, she makes biennial trips to Canada—part family visit, part trade mission to procure Twizzlers for her kids—and hosts July 1 barbecues in Germany. “I’m already in planning mode,” she says of this summer’s party, which will feature brownies, face-paint flags “and Canadian things all over the place.”

Guhr first researched her ancestor for a sixth-grade project sitting in a brick elementary school in Chatham, N.B. His political career included stints as New Brunswick’s solicitor, attorney and postmaster general, and he served as Speaker of the provincial assembly. Johnson pushed for Confederation despite opposition from some New Brunswickers who deemed him a “spiritless swaggerer.” (His death at age 50 was reportedly related to alcohol and gambling addictions.) In 1866, he signed documents to create the Dominion of Canada, an accomplishment that an 11-year-old descendant would one day recount to her class, certain that her connection was just as “cool” as her classmate’s relation to James Naismith, the inventor of basketball.

Along with an interesting family, Guhr grew up with unusual horses. Her father was a university professor but also had a barn, and she travelled around Canada with him to buy horses, adopting one named Sparrow, who had a habit of stalking her, stepping left-right-left in exact stride with the girl. “I’d never had a horse—never seen a horse—that did that,” she says. “She was the craziest one of all of them.” Another purchase, Poca, hospitalized Guhr by kicking her between the eyebrows. Poca left a dot on Guhr’s forehead that’s been there ever since.

As a safer hobby, Guhr liked to ski backwards or on one ski at night. The slope was merely a frozen garbage dump in her hometown—Guhr and her elementary-school friends once returned to the lodge carrying a pay phone—but her kamikaze tricks added danger to the three runs. To buy $17 ski poles, she made money through a clever operation in which she would pillage her house for pens, jewelry and vases. She’d then stamp them with the pricing gun from her mother’s home-decorating store and sell them back to her family at 100 per cent profit. She also converted the household bookshelves into a library, “lending” them to their owners and labelling each with a due date. “As long as they brought the book back on time, they were okay,” she explains. “They didn’t have to pay.”

Guhr would soon be swept off to Germany. She studied business at Athabasca College in Alberta, then, without a clear plan, moved to Waterloo, Ont., where her family was living at the time. There, she got a job managing customers and sales for a German company called Arvato, which builds money management software. She met a colleague, Stephen Guhr, who asked her out to the movies in Waterloo and later proposed to her amid castle ruins in Germany. The couple moved overseas, where they continued working for Arvato. They got married in a city hall, as German law demands.

Guhr’s children, Elena, 8, and Bennett, 5, are cross-cultural kids. They’re German citizens, but they attend an English school, where Elena recently outsmarted her teacher by using the word “splash pants.” The children play tennis, which Bennett began at age two and now practises with a private trainer, and they read The Berenstain Bears before bed. Elena loves licorice from Canada, while Bennett’s favourite food is wiener schnitzel, sometimes topped with a fried egg. On a four-day vacation, the five-year-old ordered a schnitzel in four cities to compare flavours. “That’s pretty much all he eats,” says Guhr. “My son is a schnitzel connoisseur.”

Guhr’s children both know about the man framed in their entranceway. When Guhr once introduced him to a guest as, “John M.,” Bennett piped up, “Who’s John M.?” The kindergartner corrected her: “It’s John M. Johnson.”