‘No dress rehearsal, this is our life:’ Gord Downie and the Canadian conversation

Opinion: Downie’s career was that of an amateur historian. He knew history as more than names and dates; for him, it was a conversation.

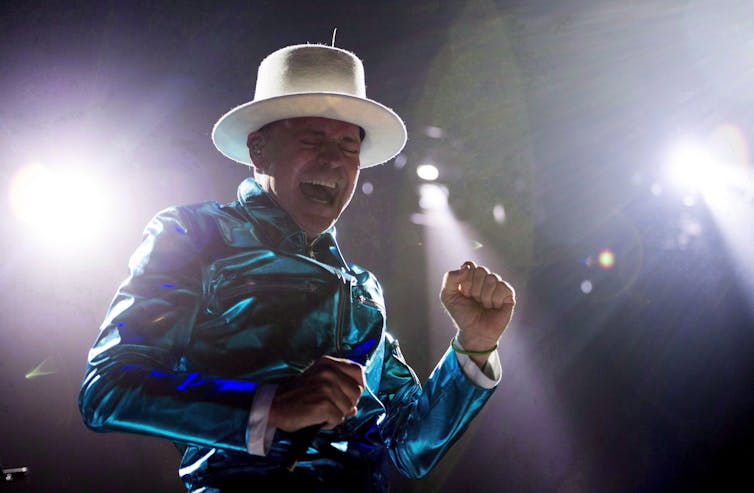

Gordon Downie, guitar and vocals, performs with the Tragically Hip at the Paradiso on February 5th 1993 in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. (Frans Schellekens/Redferns/Getty Images)

Share

Canadians are lucky to have the creative contributions of Gord Downie, frontman for the Tragically Hip, who passed away this week at the age of 53. He embodied a beautiful paradox in our conversation about Canadian culture. He wrote poetry about hockey and our complicated history, quoting both news and literature, and singing those poems to diverse audiences in hockey arenas.

Where America’s poet, Walt Whitman, spoke of “containing multitudes,” Downie connected multitudes. Like Downie, the country he loved resists summation. What is Canada? What is Canadian culture? Who is a Canadian?

READ: Remembering the life and legacy of Gord Downie (1964 – 2017)

Canadians do not agree on what it means to be Canadian. Our conversations on the subject end with more questions than we had when they began. Two approaches are often used when trying to capture the essence of Canada. The negative, “I don’t know what it means to be Canadian, but I am not American,” is countered with positive summaries like, “We are a cultural mosaic.” Downie’s work avoids such shortcuts. And somehow, that works. We like the questions.

WATCH: Gord Downie’s most memorable quotes

I first met Gord Downie while I was still in high school. It was the late 1980s and I was playing music in clubs, trying to make it in an industry the Tragically Hip were about to conquer. They were a little bit older than I was, and a whole lot better. I saw them many times in those days and followed their rise.

SPECIAL ISSUE: Maclean’s commemorates the life and legacy of Gord Downie, 1964-2017

Back when the Hip started to take off, I left the road for graduate school. I became an English professor, but I missed performance. So, I did theatre and media arts on the side, eventually completing a Master of Fine Arts in directing, extending my interests in language, performance and technology. My work as a performer and as a researcher in literary and performance studies has deepened my appreciation of the Tragically Hip.

When news broke that Downie had the same cancer that took my father a few years earlier, I took it hard. Friends and musicians from my early days called, and, because of my work, the press called. I went back out on the road to see as many of their final shows as I could. I wrote, I did interviews, I saw old friends, I sang and I cried.

The Saturday before Gord died I spent the afternoon talking with music journalist Michael Barclay who was finishing his forthcoming book on the Hip. Before we hung up the phone, we both said we hoped Gord would be with us for a long time. Barclay submitted his manuscript just before Downie passed away.

There is a lot to write about Gord Downie and the Tragically Hip, but for now I will draw on my experience and my research to share some of what I think Gord Downie’s legacy offers to Canadians and to those of us who study cultural production: writing, performance and the Canadian creative identity.

The prosperity model for art

Gord Downie was a relentless worker and a mentor to many. Just like the hockey players Downie admired, artists create work that appears effortless but requires tens of thousands of hours of labour.

Downie started as the guy who memorized more lyrics than anyone else. When he began writing, he studied poetry and spoken-word. Next, he turned to dance, and learned from experts like choreographer, Crystal Pite, to refine stage movement.

WATCH: Gord Downie memorial fills Kingston’s Springer Market Square with light and lyrics

Downie benefited from the Canadian economy and a collaborative approach to prosperity. Incentives in our economy ensured Downie’s words reached across our country — a great return on our taxpayer investment.

As a small business, the Tragically Hip followed a shared-prosperity model. Musicians make money for performing and from song rights. When they founded the Hip, all five members agreed to share writing credits equally. They said that if some members grew wealthy while others did not, the band would end.

Their collaborative business model was crucial for Gord’s success. It gave him money to live and to send his children to school, but its greatest value was the partnership. Broadcaster Ron MacLean said the band members ran the Tragically Hip like a great hockey team. Without the team, there would be no final tour. No chance to say goodbye. No one to hold him up as he travelled the Trans-Canada Highway one last time.

Great stories

Downie said Canadians had great stories that would have been famous if only they had happened in America. Downie’s career was that of an amateur historian. He knew history as more than names and dates; for him, it was a conversation.

Gord Downie mined Canadian history. For example, in Fifty Mission Cap, Downie sings about the legendary hockey player, Bill Barilko. He retold famous tales and shared those of forgotten figures like the wrongfully convicted David Milgaard. Canadians celebrate Downie for asking questions and telling these stories.

He reminds us of the importance of history and, in his constant questioning, provides an opportunity to bring us closer to what happened here, on this land, when we started calling this place Canada. “Canada is not Canada. We are not the country we think we are,” wrote Downie in his introduction to Secret Path. His rejection of nationalism was a stand against an ahistorical Canada.

Friendship, truth and reconciliation

Speaking to the University of Calgary’s Class of 2016, Senator Murray Sinclair shared his knowledge and his experience leading the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Resolving complexity into words we could understand, he told a packed arena, “All you need to do is be my friend. My job,” he said, “is to be your friend.”

Downie took this same idea of friendship to heart when writing the album In Violet Light a decade earlier. He said in order for him to improve his performance he would need to be a better friend. In the years prior to his diagnosis, he began to connect with First Nations, Métis and Northern communities.

Secret Path, recorded prior to his illness and released alongside a foundation dedicated to truth and reconciliation, tells the story of Chanie Wenjack, a young Indigenous boy who died while running away from a residential school. Chanie’s family welcomed Gord into their home; they gave their blessing and helped Gord tell their story.

Downie spoke of this work as the most important of his life. Speaking from the stage during his final performance with the Tragically Hip, he called on the prime minister and all Canadians to build the Canada we could have if we lived a little more like the Canadian stereotype we sometimes wished were true.

Lyrics as a conversation

Downie was a performance poet who knew the power of language. He was a writer with a love for words, but he wrote for the performance. He wrote lyrics the same way Joni Mitchell and Leonard Cohen did, but he worked on performance in a manner more like David Bowie.

He told interviewers his writing was not complete until it was performed. He referenced John Cage on this point, adding that every performance is one more attempt to complete the work. This iterative approach to art is pure performance. Where Whitman spoke of contradicting himself, Downie was consistent. He integrated all aspects of his role in the service of his message.

In this, Gord Downie reminded us politics can be collegial. A brief example of this emerged on Parliament Hill, the day after his death.

On Oct. 18, members of parliament from all parties rose to honour Gord, then joined Speaker of the House Geoff Regan in a moment of silence. After that, it was business as usual: people yelling at each other. During interviews in the hallways, representatives from the New Democratic Party, the Conservatives and the Liberals joked more than once that only Gord Downie could get them to agree.

Were there any students in the gallery for the Downie moment? Let’s hope so.

The conversations Downie started were a public act. Whatever our scholarly or political interests, maybe we could all work to be more collegial and try to be better friends. To do that we need to hear one another.

![]() Gord Downie heard us, and we heard him. He was a lucky man, who worked hard to make the most of the opportunities Canada provides. In the end, his greatest contribution was to get people talking. If he leaves one lesson, perhaps it can be found in these two lines from a song on In Violet Light, “Let’s get friendship right / Get life day-to-day.”

Gord Downie heard us, and we heard him. He was a lucky man, who worked hard to make the most of the opportunities Canada provides. In the end, his greatest contribution was to get people talking. If he leaves one lesson, perhaps it can be found in these two lines from a song on In Violet Light, “Let’s get friendship right / Get life day-to-day.”

Patrick Finn, Associate Professor in the School of Creative and Performing Arts, University of Calgary

This piece was originally published at ![]() .

.

Read the original article.