The Toronto tunneller finds a kindred spirit

When an engineer read Elton McDonald’s story, he knew they had to talk ‘tunneller to tunneller’

Share

Last month, Elton McDonald, the 22-year-old construction worker who built the cavernous “mystery tunnel” near his home in north Toronto (the one that captured international attention, sparked misguided rumours of terrorism and espionage, and earned McDonald the sobriquet “Lord of the Underground”), found himself in a boardroom in Mississauga, Ont., taking a history class.

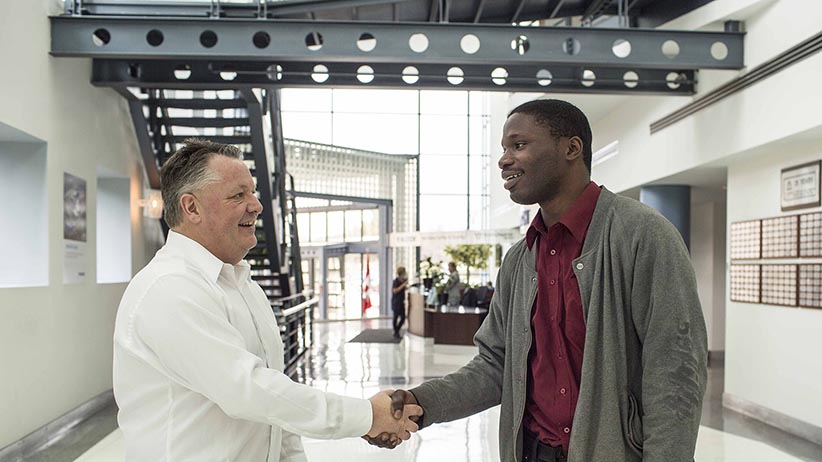

The teacher of the class was Gary Kramer, vice-president of tunnels at Hatch Mott MacDonald, a North American consulting engineering firm whose projects include the 2012 western extension to Calgary’s light- rail system and the modernization of the Los Angeles International Airport. Kramer had read a Maclean’s story about McDonald’s tunnel (dubbed the “coolest fort ever” by former Toronto police chief Bill Blair) and felt compelled to speak with him, “tunneller to tunneller.” “I love tunnels and you love tunnels,” Kramer said across the table to McDonald. “I had to talk to you.”

Specifically, Kramer, who’s been building tunnels for more than 25 years, wanted to show McDonald that digging into the earth could be more than just a passion or a hobby; it could be a career—a way to see the world and literally change it.

RELATED: The incredible true story behind the Toronto tunnel

Kramer’s lesson began with a PowerPoint presentation on a large-screen TV hanging over the table. First came a whirlwind history of tunnels 101, from hand-hewn tunnels built by the Romans in ancient Israel, to London’s famous Thames Tunnel, built in the 19th century, which took 18 years to complete and killed six workers.

McDonald was lucky he wasn’t killed himself; Kramer interrupted his presentation more than once to remind him. “Tunnelling is a tough environment. You were damn lucky,” he said. He wasn’t “chastising” McDonald, he said, so much as “channelling” him.

But in what direction? Ever since news of McDonald’s 10-m-long tunnel went viral in March, life for the neophyte tunneller with the high school diploma and impeccable manners has become a bit surreal, to the point where he’s sometimes recognized on the street. The crowd-funding campaign he launched recently to finance a summer landscaping business (one that will employ kids in his neighbourhood) raised more than $18,000 in two months. He acknowledges that a lot of good things are happening to him, but he needs to figure out what the next step is.

Face recognition, he’s aware, will not get him the post-secondary credentials he needs to pursue tunnelling full-time. Kramer has offered to coach him on what steps he might take to apply for an engineering program, or help steer him directly into contracting work, which wouldn’t require such extensive formal education. “When I was in high school I didn’t know what I wanted to do,” said McDonald. “But I might enjoy going back to school now. I think I’m a little more motivated.”

Either way, Kramer has an unstinting dream for McDonald: “I want to motivate you to become the next wave of tunneller.”

If the statement rings dramatic, it’s fitting. Kramer was working as a carpenter on a musical production at his Kitchener, Ont., high school in the 1970s, when a visiting architect, impressed by his set, suggested Kramer pursue structural engineering. When Kramer saw pictures of McDonald’s tunnel in the news, he had a similar intuition. “The size of everything [in McDonald’s tunnel] was about right. He wasn’t learning on the fly. He had a sense for it.”

Even McDonald’s spirit seemed to be in the right place: The rosary and poppy he placed at the entrance of his tunnel for protection (totally baffling the authorities) reminded Kramer of Saint Barbara, an early Christian martyr considered to be the patron saint of miners and anyone else threatened by thunder, lightning and fire (in a modern context: explosions). “In all tunnels we put up a note or a shrine to Saint Barbara,” Kramer said. “It never gets damaged or altered.”

After Kramer’s lesson ended, he led McDonald into the building’s cafeteria, where he introduced him to a group of lunching engineers, proudly mentioning McDonald’s bona fides in the process. One older engineer wearing a bow tie turned completely around in his seat to look at McDonald, genuine shock on his face. “You did that tunnel?” he asked.

“Yes,” said the Lord of the Underground. “I did.”