The incredible true story behind the Toronto mystery tunnel

Why Elton McDonald built the Toronto tunnel that captivated the world

Share

The digger Elton McDonald grew up on what’s probably the toughest street in Toronto—maybe even Canada—and he still lives there with his mother and two sisters. Three summers ago, a man got shot in the head behind their townhouse. Elton’s sister Anora Graham went to the man’s aid, pressing a shirt she’d run to fetch against the wound. He died two weeks later. Lots of others here have, too. “Elton went to school with kids who are not alive anymore,” says Anora. “They died when they were 16.”

The townhouse, in a public housing development in the city’s far northwest called Driftwood Court, is small: a kitchen and living room on the ground floor, three bedrooms on the second. Every now and then, Elton and his sisters start watching the same movie on the TVs in their three separate rooms—as they did not long ago, with Life of Pi —keeping their doors open to chat across the hall during commercials. Sometimes they call their mother, Tracy Graham, who sleeps in the basement, to see if she’s watching, too.

A print of a dark-skinned Madonna and Child hangs in the living room. “It’s good to believe in something higher than yourself,” says Tracy, “and to us, that’s God.” Tracy is 40 and cleans houses for a living. She arrived in Canada as a child, but you can still hear the Jamaica in her voice. Her own kids were still toddlers when they moved to Driftwood Court in 1995. Now Anora’s 24, Elton 22, and Tracyann McDonald, whom they call Shantay, 21. “I used to think Tracy was a little crazy,” says Sytha Sorn, 30, who’s lived next door since before they arrived. Sytha laughs. “She’s not. She’s very loving, very caring. She’s just very outgoing and very loud.”

Elton is quiet. “I spend a lot of time thinking,” he says. “I don’t talk a lot, but my mind is working overtime.” The tunnel that Elton built, a 10-minute walk from home in the ravine below Driftwood Court, was his portal into a world of quiet. He’d slip out his front door, down through the trees, and skip between the rocks across the creek—sometimes, if it was too swollen with rain, he’d lay a ladder across it, like a bridge—then climb to the spot where he dug the hole. “I was getting away from regular things, away from life,” he says. “Nothing in particular. Just life itself.”

In January, a conservation officer drawn to the site by a strange new mound of dirt uncovered that hole, and found a ladder that dropped into the darkness as into a secret cave from One Thousand and One Nights.

First reported by CBC News last month, the mystery tunnel made international news: 10 m long, more than two metres high, and expertly constructed, braced and camouflaged, it featured water-resistant electric lights and drew power via underground wiring from a generator in a soundproof, subterranean chamber nearby. A sump pump worked to suck up groundwater seepage. Police announced they needed the public’s help to identify those behind the tunnel, which likely took weeks to build, probably even longer. They described a rosary and a Remembrance Day poppy strung up on the wall.

The hole triggered worldwide speculation that it was part of a terrorist plot aimed at disrupting the 2015 Pan Am Games, some of which will take place in July at the Rexall Centre, as well as elsewhere on the nearby York University campus. On Twitter, it became the #terrortunnel. But it ended being Elton McDonald, a young construction worker from a tough neighbourhood on the other side of the Black Creek ravine. It was his fifth try at building underground, and it would take toil, determination and the better part of two years to get it done. It took pursuing a kid’s dream into adulthood. And in the end, even Elton’s father, a farmer in Black River, Jamaica, whom Elton has not seen in many years, had heard of that tunnel. “He didn’t know it was me,” Elton says. “He’s proud. He thinks it’s cool.”

For the kids of Driftwood Court, and for Elton, in particular, it’s hard to overstate the importance of Black Creek, which meanders picturesque through thick brush under the shabby, bunker-like facades of the public housing development. The treed ravine slopes up steeply on either side and, in Elton’s childhood, this landscape became common ground for the offspring of the different families here—Somali, Jamaican, Cambodian—a wilderness of tree-climbing and bug-collecting and tobogganing in winter. Elton never grew out of it. “You can get lost in there,” he says, “like you’re somewhere else completely.”

Elton and his sisters grew up catching fish, snakes and frogs, hearing woodpeckers, glimpsing deer or fox, a trio of urban Huck Finns. “It was almost a zoo to us,” he says. Years ago, Elton’s dad caught a turtle in the creek waters here, carrying it home and putting it in a box as a pet. But the turtle proved too wild and, after they returned it, Elton swears he’d see it on his walks, like a ghost. Another year, Elton and his sisters surprised their mom with a Christmas tree they dragged from the ravine, leaning it against a wall in the townhouse on its stump.

Black Creek was perfect, too, for games of cops and robbers, manhunt and tag—away from the alternative universe of Driftwood Court, where those games were deadly and real. Up there, if they heard gunshots, kids judged how close or far they sounded before deciding to go inside. Some days, they didn’t leave the house. Elton was playing basketball once when he saw three masked gunmen emerge from the ravine; later that night, he heard machine-gun fire for the first time. It’s not for nothing the words “My trust is limited” are inked into the inside of his right arm, the tattoo a gift from Tracyann. “I’ve seen stuff,” he says.

Elton is six foot, weighs 180 lb., and is lithe. When he walks, it’s a smooth process despite his size, like he’s gliding on skates. His quick, craggy grin feels just as otherworldly. “He’s strange and caring all at once,” Sytha says, “like a gentle giant. He never gets into fights. For all the years I’ve known him, never ever—unless it has to do with his mother. That was the one time I’ve ever seen him angry.”

Related reading: ‘To me he’s a folk hero, so I wrote him a song’

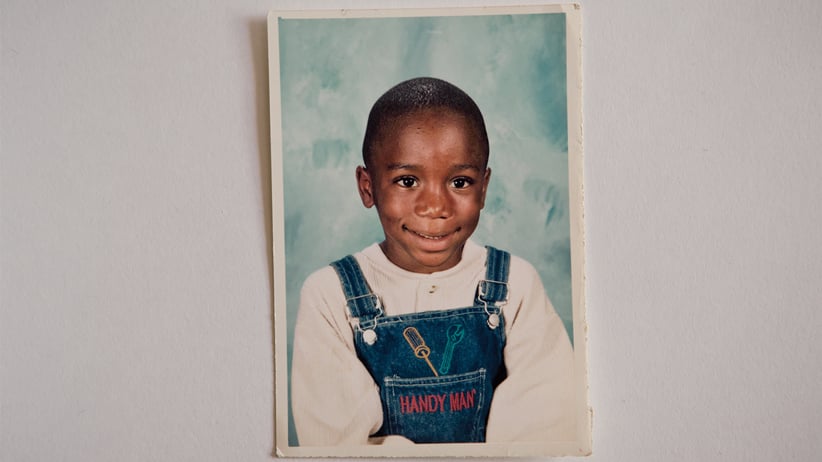

He has always been a builder. There’s a photo of him as a little kid wearing blue-jean overalls emblazoned with the words “Handy Man,” under a yellow screwdriver and a blue wrench. “I have memories of not wanting to take them off,” he says. He’d pull things apart and put them back together again, and stopped to watch at construction sites. “Since he was small, he was always a fixer,” says Tracy. “Or break it, then fix it,” says Tracyann. He made his first money scavenging broken-down lawn mowers and fixing them to cut grass around Driftwood; he made as much as $400 a summer.

Elton tried building his first subterranean structure in middle school with the same kid who’d later help dig the tunnel that made him famous (that young man doesn’t want to be identified; let’s call him Jim). Elton thought of digging a big square hole, then covering it over with earth—less a tunnel than a bunker. He started that, but grew discouraged and quit. Three more attempts just led to holes that filled with water. They were too near the creek, Elton says. Besides, he wasn’t ready.

He worked his first construction job in the summer after Grade 7, hauling two-by-fours for $15 an hour. He could not get enough. Later, a co-op program at Westview Centennial Secondary School changed Elton’s life. He worked for Boko “Bob” Marich, whose family business, Zden Bomar Contracting Inc., does heavy construction around Greater Toronto. Originally from Croatia, Boko took to Elton in a way he didn’t with most students. “I realized his potential from the second day he came,” he says. “I show him one thing to do, he’s going to multiply it by five. He’s going to do it right, he’s going to do it fast. “

Building was a passion both men shared. “Because he wants to be a builder, he’s asking me questions all the time,” Boko says. “Other students, they were not on time, they were lazy, they were not interested. I was calling them pencil pushers.” Elton was no pusher of pencils. When he graduated from Westview in 2011, he became a regular member of Boko’s crew. He learned to frame, drywall, paint—and thrived. “I told him so many times, ‘You just listen, you be who you are and time will develop you to be a good builder—even better than I am,’ ” Boko says.

It was in the summer of 2013 that Elton started in on tunnelling for the fifth time. He was ready. “I knew 10 times more,” he says. “The engineering of everything—the water, the land, the kind of dirt.” He’d found the perfect spot, too: hidden in a clump of brush, where the earth was not too moist and where, after digging a test hole, he discovered a proportion of dirt to clay exactly as it should be. And there was something else. Looking out across the creek to the opposite rise, he could see the townhouse in the distance, the grey block of Driftwood Court.

Using discarded beer bottles and a tape measure, he laid out his plan: The tunnel would head north 10 m, with two rooms like wings branching off east and west. Elton cut a manhole-sized circle into the earth with a shovel and began to dig. Soon, he’d got far enough that he needed a ladder. In the yard behind the townhouse, he made one of junk wood. This caused concern in the family. “Go buy a regular ladder,” Anora told him. “I was—‘Elton, this isn’t safe!’ ” Now he could get in and out of his hole (he later scrounged a store-bought ladder). It took two seven-hour days to get four metres down. He shovelled through water and, with a garden hose, siphoned out what he could, sucking at the rubber until he tasted dirt.

Elton is telling the story of how he built his tunnel at a McDonald’s near the Steeles and Jane intersection, not far from where he lives. He is excited. “Don’t talk so loud,” says his older sister, Anora, sitting beside him. He shifts smoothly into a lower register.

At first, he spread the dirt out thin across the ground, hiding it in the grass. He worried that residents of a high-rise overlooking the ravine might see him digging. Sometimes, York University students took a shortcut nearby. “I was thinking, ‘Is this something I should be doing?’ ” he says. It was not his land. “I don’t want to say it didn’t matter. Honestly, I loved it so much. I don’t know why I loved it. It was something so cool, so under the radar. I never really thought I’d get that far.”

He wore plastic bags over his construction boots to keep his feet dry in the hole, a mask to keep the dirt from his mouth, and he ignored the mosquitoes. He made the tunnel entrance below wider than the mouth above, tracing an outline into the north face with a small pickaxe and starting in on the horizontal.

It was at this point he knew he could go no further alone. He needed help to get the dirt out. He called on Jim, a friend from the neighbourhood still in his teens, who has been involved in all four of Elton’s tunnel attempts in the hills below Driftwood Court. Anora calls him a good-looking, introverted kid with a talent for math. “He’s like family to us,” she says. “We have his back, and make sure he doesn’t go down the wrong path.” Elton knew he could trust him to keep a secret. “I was going to get it done, just me and him, or not get it done at all,” he says.

They began collecting buckets—they’d amass 50 of them, some from Elton’s work, some from a local wine-making enthusiast—and Jim’s job consisted mainly of hauling dirt. The work was hard, and they’d dig any chance they got: on weekends, after work, putting in six hours at a time. Some mornings, Elton climbed up out of the hole at 5 a.m. so he could get home covered in dirt while it was still dark. Progress could be slow—a few feet a day. “Either way, the dirt had to leave the tunnel,” he says. Now and then, they came across rocks and dragged them out; one boulder two or three times the size of a basketball they cinched with a chain to pull out.

Jim wasn’t always happy, and even Elton had his concerns that the tunnel, which between them they called “the Hole,” or the “H” wouldn’t work. “There were times I doubted,” he says. “There were times when both of us thought it was pointless.” They’d take time away from the work now and then, a week here, a month there. But while Elton always recovered his enthusiasm, Jim’s concerns were more pronounced, and it could be hard to get him to the site. Elton had to coax him, especially at those crucial moments when inattention might spoil all they had already done.

Such a moment came two months in, when the tunnel reached 3.5 metres in length. Now, when Elton and Jim climbed down, they’d find evidence the ceiling was collapsing. A metre of earth divided the tunnel’s ceiling from the surface overhead. Several times, they’d hear a grumble, then the dirt fell in; Elton saw what he calls “crumbs” of soil on his shoulders. They had been playing music while they worked; now they stopped, the better to hear the telltale sound of the ground shifting above. Elton knew he couldn’t just rely on his ears. “It’s not like the dirt’s talking to me, telling me when it’s going to happen,” he says.

He’d always known he’d need to brace the interior of the tunnel. Many of the tools he used so far he’d borrowed from Boko, modifying one shovel for manoeuvrability in tight spaces by shortening the shaft. Now he asked Boko for the lumber he needed to reinforce the tunnel. At first, Boko had thought Elton was finishing his basement. Now something told him that wasn’t it. “I realized he’s digging, excavating,” Boko says. “I said, ‘Be careful, man! If you don’t do it right, people won’t pay you! Ask and I’ll give you advice!’ ”

Elton laid a sheet of thick construction plastic down on the tunnel floor, with holes punched through to permit groundwater to flow. On top, he spread a layer of gravel, then placed large bricks equidistant on either side of the narrow passage, not even a metre across, spacing them every metre or so along the walls. This was his foundation. He dug a water trap to collect all the moisture seeping in—large enough to catch a day’s worth. (Sometimes Elton arrived to find a metre and a half of water down there, and slugs on the walls.)

He could start framing now. It went fast—a day’s work. Elton nailed two-by-eights together in pairs and laid these lengthwise against the wall atop the bricks. He hoisted the longer ribs of wood up vertically along the walls, reinforcing these with more two-by-fours running above, and installed plywood against the ceiling.

He wanted a tunnel that would last and that was secret. “If this had been known—what’s the point?” he says. He’d take a different route to the site each time he went (a trick his neighbours used to thwart the layabout robbers who hang out on Driftwood). He made a shallow box he filled with dirt, and fit this into the mouth of the tunnel—an invisible door. In the spring, he’d have planted grass in there.

At home, they knew Elton was up to something. He’d come home filthy at all hours and, suddenly, the townhouse was full of dirt—“dirt everywhere,” Anora says. It seemed to Tracy that all she did was sweep, and still there was dirt, and you knew Elton was home when you saw the big footprints in the shower. He started measuring his progress against just how dirty he had to get. “After a while, I started coming out clean,” he says.

All this created not a little interest at the townhouse. Anora, in particular, imagined Elton building, as she puts it in her rapid-fire way, “some kind of underground house.” She admits to hounding him. “I’m the kind of person, I want to know what’s going on,” says Anora. “Me and my mum were talking about going to follow him.”

An aspiring commercial photographer, Anora quit her job as a telemarketer not long ago after reading the 1959 self-help classic The Magic of Thinking Big, and she often visits with Elton to give him what she calls “life talks.” She encourages him to break free of his shell, to break cycles, to leave his comfort zone and to dream of spectacular futures. She says it’s about “not being another statistic, getting free of negative stuff.” Still, she has sympathy for Elton: “three girls, hot-headed temperaments, him being the only boy—he’s done,” she says. “He builds, and mostly tries to stay out of the arguments.”

Tracyann, closer in age to Elton than Anora and something of an ally, worried about hints her brother was dropping that he was doing dangerous work in the woods. She asked him to leave a hand-drawn map showing approximately where he went on his outings, so that if he did not come home, they could find him.

One day, in a bus shelter across the street from the Redpath sugar refinery, on Toronto’s downtown waterfront, Tracyann found a mysterious leather pouch. She opened it and a wooden rosary with a hand-carved Jesus poured out. This she blessed, ridding it of spiritual baggage—“bad vibes,” she calls them—just the way her mum had taught her. She gave the rosary to Elton, who nailed it to the tunnel wall with a Remembrance Day poppy in the spirit of the gift—as protection.

Meanwhile, he kept at his work on the eastern slope of the Black Creek ravine. He scrounged a generator and sump pump, installing them in a hollow he dug near the hole and that he lined with soundproofing foam. Down below was mosquito-free and cool in summer and, in winter, it was warm. He and Jim brought chairs down, listened to music on a laptop, or watched movies—Edge of Tomorrow with Tom Cruise, Scarface with Al Pacino. In summer, they barbecued chicken and sausages at the mouth of the hole under cover of the brush.

“It was pretty cool,” Elton says, smiling and looking down. The last time he visited was last Christmas. He was going to leave the tunnel there, maybe never visit for five years. Leave it to settle, like a fruit that needs ripening. “I’d always know it’s there—something outside of this world.”

Elton hadn’t been to the tunnel for weeks when he first heard news that a bunker had been found in Toronto. It had to be someone else’s, he thought; his hole wasn’t under the Rexall Centre, like the one in the news reports. Then he saw the police photographs, and recognized Boko’s tools in the snapshots. When he heard news people talk about the bunker in connection with terrorist groups like Islamic State, he thought that any minute a SWAT team would descend on the townhouse. “Anora,” he said, “that thing that I was doing is on the news.”

Tracy, Anora and Tracyann watched the reports with rapt attention. They’d seen Elton trundle down into the woods with a shovel and a couple of buckets. What they saw in those tantalizing police photos was like nothing they thought Elton could do. “I surprised them,” he says. “It looks like our house’s hallway,” says Tracyann.

In the Driftwood Court townhouse, discussion turned to what they should do. Except for a brush with the law several years ago—Elton says a gun that police uncovered in the townhouse was planted, and the charges laid against him eventually went away—Elton has kept out of trouble. Nevertheless, the family was skittish about telling authorities the tunnel was his.

The next morning, Elton went to work as usual. Boko, too, had seen the news and recognized the tools in the photos. As soon as they saw each other, Elton told him he was the guy who’d built the tunnel on television. “He was laughing, because he couldn’t believe it was me,” says Elton. But Elton was worried. He asked Boko what he should do. “I will find out,” Boko told him. “You don’t have to worry.”

Despite those words of encouragement, Boko, too, was worried. He did not go immediately to police, but instead sought out an intermediary—someone who could give him assurances this was not a criminal matter, and that Elton would not be charged. He reached out, without success, to Toronto Mayor John Tory, then to former mayor and current city councillor Rob Ford. Next, he turned to Ford’s older brother Doug, himself a former Toronto city councillor, and an acquaintance.

According to Boko’s account, he explained his predicament to Ford at the latter’s private business offices at Deco Labels and Tags. Ford, now a private businessman, told him he knew just whom to call, and left the room. Minutes later, Ford returned and informed him that whoever was behind the tunnel was unlikely to face charges. But he went on to say it was Boko’s civic duty to inform authorities, who were in the midst of an expensive investigation to track down the mystery digger. Boko says Ford asked him if he’d object to his inviting police to speak to him at Deco Labels. In a few minutes, Boko was in conference with investigators. “They told me not to talk to no one—not even Elton,” he says.

Soon after, Elton got a call at the townhouse. It was the police. “We want to talk to you about the hole you dug,” an officer told him, and asked that he come down to 31 Division, the busy Jane and Finch police station. “I thought there was a chance I wouldn’t come back home,” says Elton.

Doug Ford had been right: There would be no charges. Toronto police, announcing they’d unravelled the mystery, said two men had built the tunnel for “personal reasons.” Chief Bill Blair later told reporters this was not unexpected: “One of the theories was maybe this is just the coolest fort ever.” All Elton got was a little advice: “Don’t dig any more holes,” the police told him.

Yet his discovery did not come without punishment. The police filled in the tunnel. “It took a couple of years to do it and it took them one day to fill it up,” he says. He misses just knowing it was there, and the family feels his sense of loss. “I’m sad they found it,” Tracy says.

Elton first revealed his identity in an interview with the Toronto Sun. The media attention this unleashed surprised everyone. Journalists congregated outside the townhouse and tried to charm Tracyann into interviews through the window (Tracyann is not easily charmed). They staked out the parking lot at Driftwood Court. Others showed up at Boko’s work sites, looking for Elton or anyone who knew him. “That was him!?” one man who’s worked with him (and who has been so disgusted by the performance of the Toronto Maple Leafs that he stopped watching the news entirely) asked a reporter last week. “Get outta here! I thought it was al-Qaeda!”

The media storm forced Elton to take time off work and to hole up in the Driftwood Court townhouse. And he got to thinking. Months ago, Anora’s life talks had turned to what Elton wants to do with his life. Now she was starting to use Elton’s escape hatch to spin new homilies. “I use this now as an example. ‘You put your mind to something,’ ” Anora says. “ ‘You manifested your dreams.’ ”

Here was a chance to make more of his dreams a reality. Elton thought about his future, how he wants a contracting business like Boko’s. And he thought about the kids of Driftwood Court. He envisions a summer program that will give neighbourhood kids a chance to work cutting grass like he did, even do some light landscaping. It’s not just about creating summer jobs. “I’ll make a new definition of cool—because what I think is cool now is having your own house, getting married,” he says.

Last week, he launched an online fundraising campaign, called Eltons Tunnel Vision Fund, to help get his contracting business and that summer program up and running. His goal is $10,000 by summer. (Update: Two days after this story was published, McDonald met his goal, thanks to many supporters.)

“I’m going to be a big contractor one day,” he says. “And I want to be a good parent.”

“And you’ll teach your kids like I did,” his mother, Tracy, says. “You got to break the cycle somehow.”

Will he ever build another tunnel? “It’s something, for sure, I’m going to do again,” he says. “When I have my own property.”