With stained glass and service, a Toronto church remembers the fallen

The walls and windows of St. Paul’s record its dead. Still, mysteries remain.

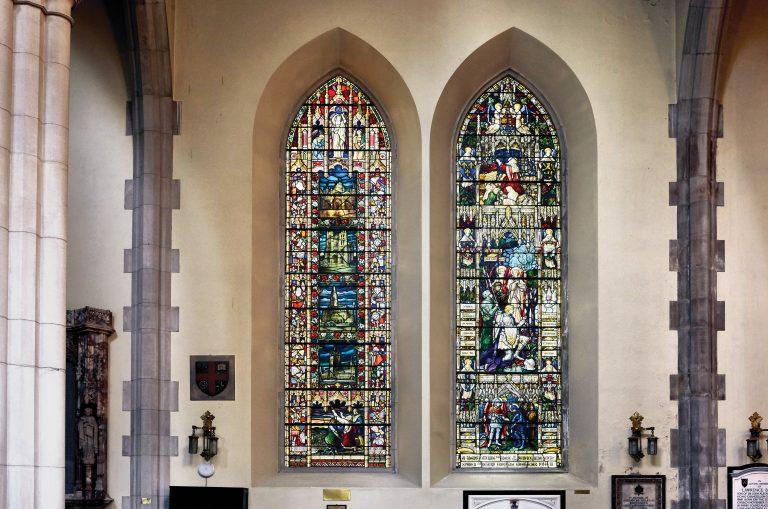

The window for the fallen and window for the living inside St. Paul’s, Bloor Street. (Photograph by Christie Vuong)

Share

In November 1913, some 2,500 of Toronto’s most prominent citizens witnessed the opening of the third iteration of St. Paul’s Church on Bloor Street. Celebrity architect E.J. Lennox had created a light-filled, neo-Gothic interior that was—and is—the largest Anglican church in the city. Its walls were bare, its tall windows filled with clear glass. They would not stay unadorned for long.

Eight months later, Canada was plunged into the First World War. Those years would transform the church, just as it did the country. Ontario’s capital city was the epicentre for the young nation’s volunteer army, and St. Paul’s was no exception: virtually every able-bodied man of military age had enlisted by the time the war ended.

READ: Why we’re honouring exactly 66,349 Canadians who died in the First World War

In an era before community centres and other secular gathering sites, it was churches and other houses of worship that were the hearts of neighbourhoods and communities. For four years, the Rev. Canon Henry Cody stood at the imposing pulpit of St. Paul’s to deliver the latest war news alongside his sermon. It was a litany of sorrow. Of the more than 500 men and seven female Nursing Sisters who served from St. Paul’s, 76 died.

One hundred years later, time has frayed the links between that generation and today’s. Yet there is a renewed interest in that era. Last year, for the church’s 175th anniversary and for Doors Open—the weekend during which the public is invited to traipse into normally closed buildings—St. Paul’s volunteer archivists (including this author) created a tour, “From Titanic to Vimy Ridge,” focusing on the church in the 1910s. Nearly 1,000 people visited St. Paul’s; many asked about the war years and the men who served.

So now, as the centenary of the end of the Great War approaches, we archivists are again delving into fragile records, this time to keep soldiers’ names and stories alive. They are ever-present. Even while the war was grinding on, memorial services for the dead were being held, plaques were being mounted on the church’s walls and stained-glass memorial windows were being planned. Today, there are few blank spaces left on the walls, or clear glass windows. The sheer volume of remembrance (three sets of stained-glass windows and two memorials for communal recognition, as well as family-ordered plaques and windows) bears homage to the toll inflicted on the congregation: everyone would have known someone who died, and they were determined to honour their memories in a manner befitting of the era.

The men killed during the war were a cross-section of the city: clerks, tradesmen, university students and professionals. Pte. Arthur Lusty had been a bricklayer, while Maj. William Crowther was already in the army when the war began. Some were astoundingly brave, earning multiple commendations. Others are all but anonymous. The youngest was 17, the oldest 38. Most died in their early 20s.

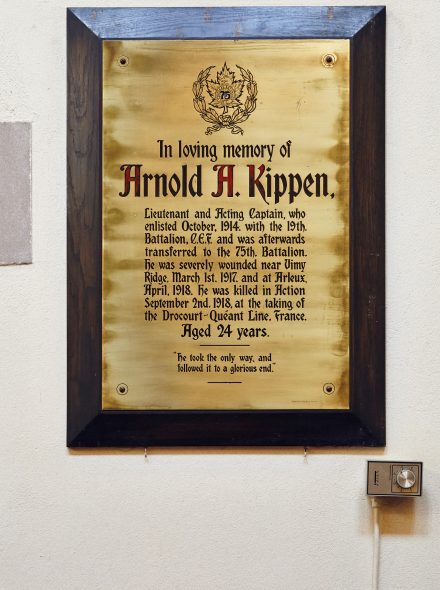

Their stories resonate when research deepens the tales told on the church’s walls. “He took the only way and followed it to a glorious end,” is the inscription on one plaque. It is for Lt. Arnold Kippen, who was a 20-year-old bank clerk when he signed up in November 1914, just after the war began. Though seriously wounded twice, including during a gas attack at Vimy Ridge, he rose through the ranks to become an officer before being killed on Sept. 2, 1918, when Canadian forces took the Drocourt-Quéant Line in France. A week later, a cable with news of his death arrived at the Toronto home of his parents, Horace and Elizabeth Kippen. The next day, another message arrived informing them that another son, William, had been severely wounded. If that wasn’t enough, their third son, Eric, was a prisoner of war. (Arnold’s brothers survived.)

The 76 dead were all men, and as far as we can determine, white—in 1914, of a population of more than seven million, Canada had fewer than 150,000 Indigenous peoples and visible minorities. Many belonged to the Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada. Founded in 1860, it drew many of its members from the Toronto area, and St. Paul’s is its regimental church: its Cross of Sacrifice, recording battles from the Fenian Raid to Afghanistan, stands outside, while inside is a memorial and book recording all the regiment’s dead, including some 2,200 during the Great War.

Not all were soldiers: at least 12 were pilots in the nascent air forces. One was Flight Commander Arthur Gerald Knight, a student in Toronto when he joined the Royal Flying Corps. He is credited with downing at least eight enemy planes and was awarded the Military Cross and the Distinguished Service Order. He was killed by Manfred von Richthofen (the Red Baron) on Dec. 20, 1916. He was 21.

Like many historical hunts, getting ready for the 100th anniversary revealed more than its share of mysteries. For one, there was no consistent list of the church’s war dead, even though their names are etched on memorials created within a few years of each other. On the ornate alabaster screen behind the altar, the names of the dead are carved by year of death. That list doesn’t perfectly sync with the big memorial at the other end of the church, which alphabetically lists all those who served, the dead marked by small red crosses. Even more confusing, those two memorials don’t completely line up with the names and dates of death printed in the order of service for the unveiling of the grand stained-glass windows above the altar by governor general Lord Byng of Vimy in 1921. (Errors were everywhere: the day’s order of service spelled Byng’s name as “Bing.”)

Some of the inconsistencies reveal the grief of families: The name of George Kappele is shoehorned onto the ornamental screen, clearly added as an afterthought on behalf of his relatives. It turns out that George, a militia officer and recent law school graduate, had just signed up for war when he accidently shot himself at home while trying to kill a bat in 1915. Eight days later his brother, Ernest, signed up. He was killed at Vimy Ridge in 1917. The Kappele brothers are one of four sets of siblings from St. Paul’s who died during the war.

Others errors are inexplicable. In May 1918, Lt. Gordon Ross was killed while blockading the harbour at Ostend, Belgium. Though his family put up a plaque, his name on the Great War memorial doesn’t have a red cross next to it. Others appear to be mistakes. Lt. Francis Roy McGiffin, a member of the 1914 Toronto Blueshirts team that won the Stanley Cup, who was killed in a U.S. military air crash in Texas in 1918, was recorded as McGiffen. A similar spelling error occurred for Sapper George Gibbons, a labourer who enlisted in 1916 and died exactly three months later in the Battle of Ypres; the church consistently recorded his name as Gibbins.

Despite months of research, some men remain stubbornly anonymous: The name of Cyril Best is on the altar screen, but we can’t find any information about anyone by that name dying in 1917 with a link to Toronto; the same mystery surrounds T. Gilfillan, who reportedly died in October 1914. It’s possible they were British immigrants who went back to fight for its military and are lost amid the millions who served and died.

Some of the church’s treasures are deeply personal: Under the large memorial hangs a raw wooden cross that originally marked the grave of Maj. Sidney Burnham in France; his family donated it to the church after a stone marker was laid on top of his final resting place in France. In the archives is an inscribed medal and a letter from King George V to the family of Lt. Aysceau Swinnerton. At the start of the war, the 22-year-old university student tried to enlist but was turned down because of poor eyesight. By 1916, standards had fallen, and he was soon an officer at Vimy Ridge, where he was shot by a sniper in March 1917. His body was never found.

Not all the wartime tributes are for those who faced action. Above a door is a window honouring Iris Burnside, the 20-year-old granddaughter of retailer Timothy Eaton, who drowned when the Lusitania, a civilian liner en route to Britain, was torpedoed by a German U-boat in 1915.

A year after unveiling the windows above the altar, governor general Lord Byng returned to St. Paul’s to dedicate yet another window to the fallen. (For the record, the church spelled his name correctly this time.) It looks like a regular stained-glass window but actually includes around 700 pieces of glass from 70 destroyed or damaged churches or buildings in the war zones of France, Belgium and Italy. The pieces were found on the ground among the ruins by a congregant, Brig.-Gen. Charles Mitchell, who, as a senior intelligence officer, was able to move around behind the lines.

This fall, that window, and other architectural tributes to the Great War, will be part of a public tour as well as a social media campaign. Both programmes will tell the stories of those men, and how a church and its congregation endured what must have seemed unendurable.

On Sunday, Nov. 11, St. Paul’s pews will again be filled. Like every Remembrance Sunday, the boots of the riflemen of the Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada will echo through the silent church as they parade their regiment’s Book of Remembrance to the altar, where it will lie during the service. During the prayers, the names of all 76 of St. Paul’s dead will be read out loud. They may have died long ago on battlefields and trenches far from Canada, but they are not forgotten.

Patricia Treble is a writer in Toronto and a volunteer archivist at St. Paul’s Bloor Street.