Conscription divided Canada. It also helped win the First World War.

Canada’s military couldn’t have carried on without the controversial policy

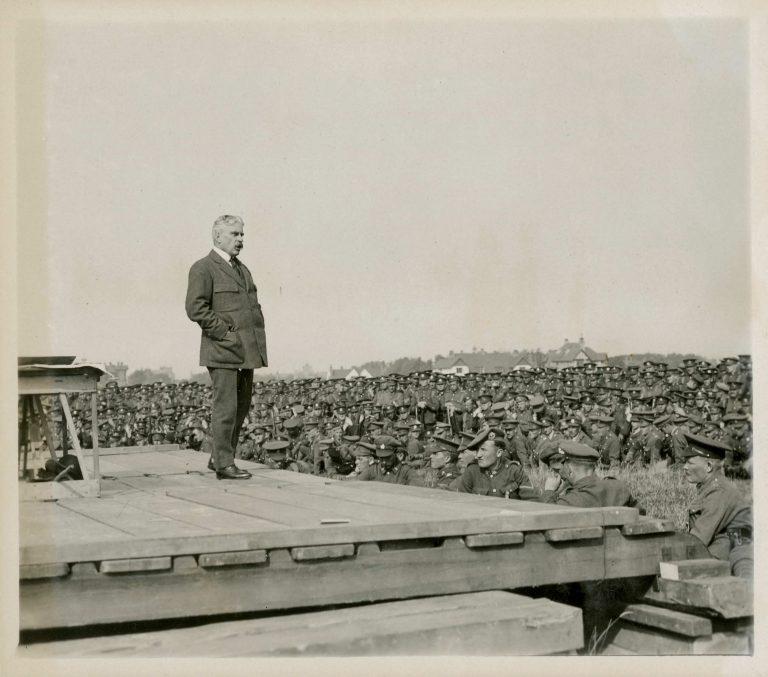

Sir Robert Borden addresses the troops. (EM-0591C/Canadian War Museum)

Share

Conscription was Canada’s most divisive issue during the Great War. Recruitment of volunteers went well into 1916, but there were some disturbing patterns. British-born Canadians enlisted in huge numbers, but English-speaking, Canadian-born enlistment was relatively low. French-Canadian enlistment was lower still, and immigrants from eastern and southern Europe had little incentive to enlist. With the Canadian Corps’s four divisions fighting in France and Flanders by the fall of 1916, and with casualties outpacing the flow of volunteers, the politicians and military planners in Ottawa had reason for concern.

Prime Minister Sir Robert Borden believed wholeheartedly in the cause, and in a 1916 New Year’s message, he told Canadians that he had authorized a force of 500,000. This was a very large commitment for a nation of just eight million, and Borden’s pledge spurred demands for compulsory military service across English Canada. Farmers—worried about the loss of workers from rural areas to better-paying jobs in munitions factories—similarly opposed the policy.

Borden was in Britain when the Canadian Corps took Vimy Ridge in April 1917, and while he was thrilled by the victory, the more than 10,000 casualties horrified him. Where could the men be found to keep the ranks full? Borden returned to Canada in May determined to implement conscription.

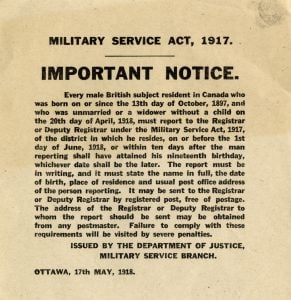

But before he introduced his Military Service Bill in Parliament, Borden met with Liberal leader Sir Wilfrid Laurier to discuss a possible coalition government. Fearing that Quebec would not accept conscription, Laurier refused, and Borden set out to pass his bill and to lure Liberals into a coalition despite Laurier’s worries. It was a hard road, but Borden persisted, his way eased by a series of extraordinary gerrymandering acts of Parliament. The Military Voters Act let soldiers vote in their home constituency or, if they did not know its name, for the government or the Opposition. Votes could be allocated where the government most needed them.

The Wartime Elections Act (WTEA) was similarly slanted. Recent naturalized citizens from enemy nations were disenfranchised, a blow for Liberal support in the West. At the same time, female relatives of soldiers received the vote, the government’s expectation being that they would support conscription. The WTEA hit hard at the reluctant Liberals courted by Borden, and they soon joined his Union Government to fight the December 1917 election. The issue was conscription, with Borden saying that no call-ups would begin until January 1918, but that 100,000 men were needed. To further increase the odds in its favour, the government promised farmers’ sons exemptions from military service.

The Union Government pulled out all the stops in its anti-Quebec propaganda. If Laurier wins the election, one flyer said, “the French-Canadians who have shirked their duty in this war will be the dominating force . . . Are the English-speaking people prepared to stand for that?” Borden handily won his election, and the conscripts began their training. In March, the Germans launched a series of successful offensives against the Allies. Panicked, the government cancelled the farmers’ exemptions, creating major protests as the planting season began. In addition, substantial numbers of men evaded the draft, and there were bloody riots in Quebec City. Canada remained bitterly divided by conscription.

The first conscripts reached France in May and were integrated into the infantry battalions in the Canadian Corps. In all, just over 24,000 men reached France before the Armistice on Nov. 11, 1918, brought the fighting to an end. This was a substantial number, more than the complement of a Canadian division, and sufficient to provide 500 reinforcements for each of the Corps’s 48 infantry battalions. These reinforcements mattered greatly because from Aug. 8 through to the Armistice, the Canadians fought their most important and most costly battles of the war. The casualties were huge—45,000 killed and wounded or almost 20 per cent of Canada’s total war casualties in less than 100 days—and the Corps could not have carried on without the conscripts.

Borden had implemented conscription because he believed the war had to be won and that Canada must play its full part. To achieve these ends, he almost broke the nation. The conscripts, however reluctant they may have been to serve, nonetheless played a critical role in winning the war.