Quebec: The most corrupt province

Why does Quebec claim so many of the nation’s political scandals?

Share

Marc Bellemare isn’t a particularly interesting man to look at, so you’d think the spectre of watching him sit behind a desk and answer questions for hours on end would have Quebecers switching the channel en masse. And yet, the province’s former justice minister has been must-see TV over the past few weeks, if only because of what has been flowing out of his mouth.

Bellemare, who has been testifying in an inquiry into the process by which judges are appointed in Quebec, has particularly bad memories of his brief stint in cabinet, from 2003 to 2004. The Liberal government, then as now under the leadership of Premier Jean Charest, was rife with collusion, graft and barely concealed favouritism, he says—the premier himself so beholden to Liberal party fundraisers that they had a say in which judges were appointed to the bench. “It happened in [Charest’s] office. He was relaxed, he served me a Perrier,” Bellemare testified. The two spoke about Franco Fava, a long-time Liberal fundraiser who, according to Bellemare, was lobbying for Marc Bisson (the son of another Liberal fundraiser) and Michel Simard to be promoted. “I said, ‘Who names the judges, me or Franco Fava?’ I was very annoyed. I found it unacceptable,” Bellemare recalls. He remembers Charest saying, “ ‘Franco is a personal friend. He’s an influential fundraiser for the party. We need men like this. We have to listen to them. If he says to nominate Bisson and Simard, nominate them.’ ”

Judicial selection may be a topic as dry as Bellemare’s own clipped monotone, yet the public inquiry currently under way has been a ratings success. It has veered into bizarro CSI territory, complete with testimony from an ink specialist who discerned that Bellemare had used at least two different pens when writing notes on a piece of cardboard. And despite his reputation as a bit of a crank, and the fact his supposedly airtight memory is prone to contradictions and convenient lapses, Quebecers believe Bellemare’s version of events over that of Jean Charest, the longest serving Quebec premier in 50 years—by as much as four to one, according to polls.

Part of the reason for this is the frankly disastrous state of Charest’s government. In the past two years, the government has lurched from one scandal to the next, from political financing to favouritism in the provincial daycare system to the matter of Charest’s own (long undisclosed) $75,000 stipend, paid to him by his own party, to corruption in the construction industry. Charest has stymied repeated opposition calls for an investigation into the latter, prompting many to wonder whether the Liberals, who have long-standing ties to Quebec’s construction companies, have something to hide. (Regardless, this much is true: it costs Quebec taxpayers roughly 30 per cent more to build a stretch of road than anywhere else in the country, according to Transport Canada figures.) Quebecers want to believe Bellemare, it seems, because what he says is closest to what they themselves believe about their government.

This slew of dodgy business is only the most recent in a long line of made-in-Quebec corruption that has affected the province’s political culture at every level. We all recall the sponsorship scandal, in which businessmen associated with the Liberal Party of Canada siphoned off roughly $100 million from a fund effectively designed to stamp the Canadian flag on all things Québécois, cost (or oversight) be damned. “I am deeply disturbed that such practices were allowed to happen,” wrote Auditor General Sheila Fraser in 2004. Fraser’s report and the subsequent commission by Justice John Gomery, which saw the testimony of Liberal prime ministers Jean Chrétien and Paul Martin, wreaked havoc on Canada’s natural governing party from which it has yet to recover.

We remember Baie Comeau’s prodigal son, Brian Mulroney, and his reign in Ottawa, which saw 11 cabinet ministers resign under a cloud in one seven-year period—six of them from Quebec. Mulroney’s rise was solidified by an altogether dirty battle against Joe Clark in Quebec that saw provincial Conservative organizers solicit Montreal homeless shelters and welcome missions, promising free beer for anyone who voted for Mulroney in the leadership campaign. Clark’s Quebec organizers, meanwhile, signed up so-called “Tory Tots,” underage “supporters” lured by promises of booze and barbecue chicken. And in 2000, organizers for Canadian Alliance leadership hopeful Tom Long did Mulroney’s and Clark’s camps one better, signing up unwitting Gaspé residents both living and dead to pad the membership rolls.

The province’s dubious history stretches further back to the 1970s, and to the widespread corruption in the construction industry as Quebec rushed through one megaproject after another. Much of the industry at the time, according to a provincial commission, was “composed of tricksters, crooks and scum” whose ties to the Montreal mafia, and predilection for violence, was renowned.

As politicians and experts from every facet of the political spectrum told Maclean’s, the history of corruption is sufficiently long and deep in Quebec that it has bred a culture of mistrust of the political class. It raises an uncomfortable question: why is it that politics in Canada’s bête noire province seem perpetually rife with scandal?

Certainly, Quebec doesn’t have a monopoly on bad behaviour. It was in British Columbia that three premiers—Bill Vander Zalm, Mike Harcourt and Glen Clark—were punted from office in short order for a variety of shenanigans by their governments in the 1990s. In the mid-’90s, no less than 12 members of Saskatchewan Conservative premier Grant Devine’s government were charged in relation to an $837,000 expense account scheme. Sir John A. Macdonald, Canada’s first prime minister—and the first to go down in scandal, with his government forced to resign—came from Ontario. And the East Coast? “The record of political chicanery is so overflowing in the Maritimes that they could likely teach Quebec a few tricks,” Montreal Gazette political writer Hubert Bauch once wrote.

Still, Quebec stands in a league of its own. Maurice Duplessis, its long-reigning premier (and certainly one of its more nationalistic), was a champion of patronage-driven government, showering favourable ridings with contracts and construction projects at the expense of those that dared vote against him. Duplessis typically kept $60,000 cash in his basement as part of an “electoral fund” to dole out to obliging constituents. His excesses sickened Quebec’s artistic and intellectual classes, and their revolt culminated in the Quiet Revolution, which brought in a large, stable (and, as far as its burgeoning civil service was concerned, faceless) government less prone to patronage in place of Duplessis’s virtual one-man show.

Yet corruption didn’t disappear; it just took another form. Under the Quiet Revolution, Quebec underwent an unprecedented modernization, both in mindset and of the bricks and-mortar variety. The latter occurred at a dizzying speed; over 3,000 km of major highway were built in the 1960s alone. But modernization came at the price of proper oversight: in 1968, referring to widespread government corruption, historian Samuel Huntington singled out the province as “perhaps the most corrupt area [in] Australia, Great Britain, United States and Canada.”

It got worse. The speed at which the province developed required a huge labour pool—and peace with Quebec’s powerful unions. Peace it did not get: the early ’70s were synonymous with union violence at many of Quebec’s megaprojects, particularly Mirabel airport and the James Bay hydroelectric project in Quebec’s north—where union representative Yvon Duhamel drove a bulldozer into a generator. As the Cliche commission, an investigation into the province’s construction industry, noted in 1974, the Quebec government under Bourassa knew of the violence and intimidation, and as author and Conservative insider L. Ian MacDonald later wrote, “permitted itself to be taken hostage by the disreputable elements of the trade union movement.”

A young lawyer named Brian Mulroney sat on the commission; he helped pen the report detailing “violence, sabotage, walkouts and blackmail” on the part of the unions. Another lawyer named Lucien Bouchard, who served as the commission’s chief prosecutor, noticed a large number of union cheques made out to the Liberal Party of Quebec, though this was never investigated.

RELATED: COYNE on what’s behind Quebec’s penchant for money politics

Apart from the arguably ironic casting of Mulroney as an anti-corruption crusader, the legacy of the Cliche commission was twofold. It spelled the end of Bourassa’s first stint as premier and ushered in the sovereignist Parti Québécois, which promptly enacted the strictest campaign financing laws in the country, banning donations from unions and corporations and limiting annual individual donations to $3,000. These laws have effectively been rendered toothless since then. According to a study by the progressive

party Québec Solidaire, the senior management at four of Quebec’s big construction and engineering firms each donated the maximum or near the maximum allowable amount to the Quebec Liberal party, to the collective tune of $400,000 in 2008 alone. The Parti Québécois and the Action démocratique du Québec (ADQ), too, benefited from certain firms’ largesse, though on a much smaller scale.

The province’s construction industry, meanwhile, remains as wild and woolly as ever. According to La Presse, a long-standing price-fixing scheme on the part of 14 construction companies drove up construction prices across the province. In several cases, according to a Radio-Canada investigation last year, these companies used Hells Angels muscle to intimidate rival firms. A fundraising official with the Union Montréal, the party of Montreal Mayor Gérald Tremblay, was found to have led a scheme in which three per cent of the value of contracts was distributed to political parties, councillors and city bureaucrats. And the industry is well connected: until 2007, Liberal fundraiser Franco Fava was president of Neilson Inc., one of Quebec’s largest construction and excavation firms.

There are some who posit that government corruption is inevitable in part because government is so omnipresent in the province’s economic life. According to Statistics Canada, Quebec’s provincial and municipal government spending is equivalent to 32 per cent of its GDP, seven percentage points higher than the national average. The province is frequently home to giant projects: consider Montreal, with its two ongoing mega-hospital projects, or Hydro-Québec’s massive development of the Romaine River in the north shore region. So there is a temptation (even necessity) to curry favour with power. “In Quebec, it’s usually a case of old-fashioned graft,” says Andrew Stark, a business ethics professor at the University of Toronto’s Rotman School of Business. “The state occupies a more prominent role, and people in the private sector rely on the state for appointments or contracts, so they make political contributions to do so. In the rest of the country it’s reversed: it’s people in public office using public money to give themselves private-sector-style perks.”

These links between private business and the public sector notably led to Shawinigate, when it emerged that then-prime minister Jean Chrétien had called the president of the government-run, and ostensibly arms-length, Business Development Corp. to discuss a loan application from businessman Yvon Duhaime to spruce up the Auberge Grand-Mère in Chrétien’s Shawinigan riding. The loan was granted. “I work for my electors, that’s my job,” Chrétien said at the time–even though he still stood to gain from his share of the neighbouring golf course. As several critics noted at the time, the golf course would have likely increased in value following the renovations.

But the factor most important to this history of corrupton may be Quebec’s nagging existential question of whether to remain part of the country. That 40-year threat of separation has been a boon for provincial coffers. As a “have-not” province, Quebec is entitled to equalization payments. In the past five years, according to federal Department of Finance data, Quebec’s share of the equalization pie has nearly doubled, to $8.6 billion, far and away the biggest increase of any province. This is due in large part to aggressive lobbying by the Bloc Québécois.

According to many on both the left and right, obsessing over Quebec’s existential question has come at the expense of proper transparency and accountability. “I don’t think corruption is in our genes any more than it is anywhere else on the planet, but the beginning of an explanation would be the fact that we have focused for so long on the constitutional question,” says Éric Duhaime, a former ADQ candidate who recently helped launch the right-of-centre Réseau Liberté-Québec. “We are so obsessed by the referendum debate that we forget what a good government is, regardless if that government is for or against the independence of Quebec.”

After nearly losing the referendum in 1995, the federal Liberals under Chrétien devised what amounted to a branding effort whose aim was to increase the visibility of the federal government in Quebec. The result: a $100-million scandal that saw several Liberal-friendly firms charge exorbitant amounts for work they often never did. The stench of the sponsorship scandal has yet to dissipate, so damaging was it to Quebec’s collective psyche. “Canada basically thinks . . . [Quebecers] can be bought off by some idiotic ad campaign,” wrote Le Devoir’s Jean Dion in 2004.

Or a new hockey arena, it seems. Earlier this month, eight Quebec Conservative MPs donned Nordiques jerseys and, through wide smiles, essentially said Quebec City deserved $175 million worth of public funding for a new arena. “As MPs, we cannot ignore the wishes of the population that wants the Nordiques to return,” Jonquiere-Alma MP Jean-Pierre Blackburn told the Globe and Mail. “In addition, our political formation, the Conservative party, has received important support in Quebec City.”

It won’t be the Conservatives’ first foray into patronage in the province. According to a recent Canadian Press investigation, a disproportionate percentage of federal stimulus money reserved for rural areas went to two hotly contested ridings in which the Conservatives barely edged out the Bloc. Now, as always, keeping the sovereignists out seems to be priority number one for the feds, and the favoured way is through the public purse strings.

The federalist-sovereignist debate has effectively entrenched the province’s politicians, says Québec Solidaire MNA Amir Khadir. “Today’s PQ and the Liberals are of the same political class that has governed Quebec for 40 years. The more they stay in power, the more vulnerable to corruption they become. There hasn’t been any sort of renewal in decades,” he says. “We are caught in the prison of the national question.” If so, it’s quite a prison. Crossing the federalist-sovereignist divide is something of a sport for politicians. Lucien Bouchard went from sovereignist to federalist and back again. Raymond Bachand started his political career as a senior organizer for René Lévesque’s Yes campaign in 1980; today, he is the minister of finance in Charest’s staunchly federalist government. Liberal Jean Lapierre was a founding member of the Bloc Québécois, only to return to Martin’s Liberal cabinet in 2004. Many Quebec politicians never seem to leave. They just change sides.

Veteran Liberal MNA Geoff Kelley says all the bad headlines are proof, in fact, of the system’s efficacy at weeding out corruption. Yes, two prominent former Liberal ministers, David Whissell and Tony Tomassi, have left cabinet amidst conflict-of-interest allegations. (A construction firm Whissell co-owned received several no-tender government contracts, while Tomassi used a credit card belonging to BCIA, a private security firm that received government contracts and government-backed loans.) No, it “doesn’t look good” when five Charest friends and former advisers join oil-and-gas interests just as the province is considering an enormous shale gas project. How about the nearly $400,000 in campaign financing from various engineering and construction companies? No one has shown any evidence of a fraudulent fundraising scheme, he counters. “I’m not saying it didn’t happen, I’m just saying it hasn’t been proven.” Kelley blames much of the government’s ailments on an overheated Péquiste opposition. As for Bellemare’s allegations, Kelley rightly points out that they are just that: allegations.

He thinks the system is working. Far from being kept quiet, Bellemare has the ear of the province, thanks to the commission Charest himself called. The Charest government, Kelley notes, will institute Quebec’s first code of conduct for MNAs in the coming months. “I’m not saying everything’s perfect, [or] everything’s lily white,” Kelley says. “Obviously these things raise concerns, they raise doubts, and I think mechanisms have been put in place to try and tighten up the rules.”

For many Quebecers, though, talk of renewal is cheap. As they know all too well, rules in the bête noire province have a habit of being broken.

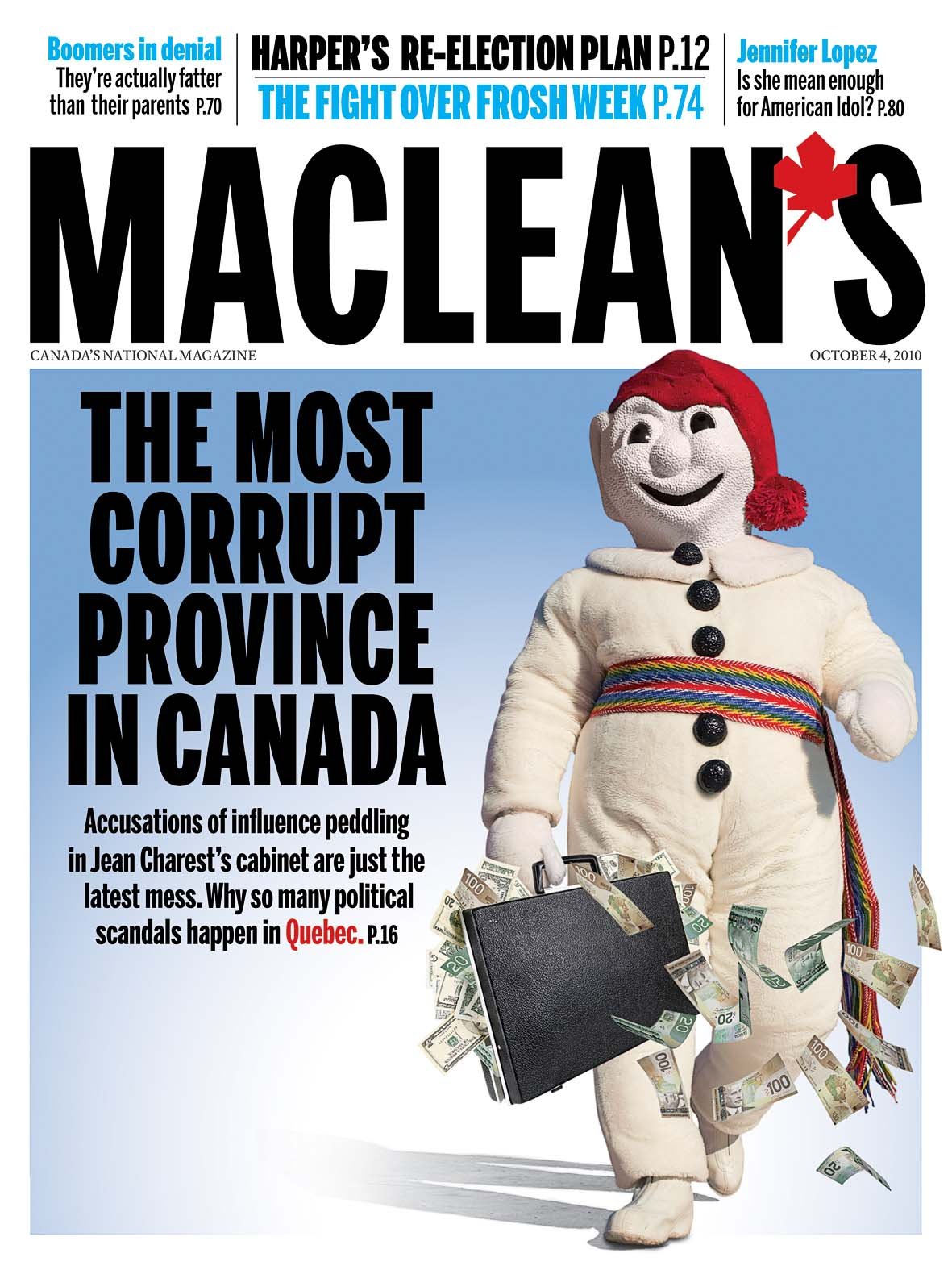

CLARIFICATION: The cover of last week’s magazine, with the headline “The Most Corrupt Province in Canada,” featured a photo-illustrated editorial cartoon depicting Bonhomme Carnaval carrying a briefcase stuffed with money. The cover has been criticized by representatives of the Carnaval de Québec, of which Bonhomme is a symbol.

While Maclean’s recognizes that Bonhomme is a symbol of the Carnaval, the character is also more widely recognized as a symbol of the province of Quebec. We used Bonhomme as a means of illustrating a story about the province’s political culture, and did not intend to disparage the Carnaval in any way. Maclean’s is a great supporter of both the Carnaval and of Quebec tourism. Our coverage of political issues in the province will do nothing to diminish that support.