Quebec’s 30-year-old wine industry is finally growing

Almost despite itself

Share

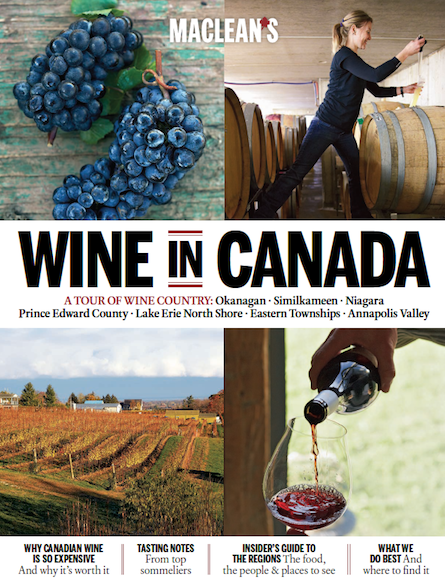

Maclean’s tells the story of Canadian wine from coast to coast in words and pictures in Wine in Canada: A Tour of Wine Country. Look for it on newsstands now. Or download the app now. In the meantime, here’s a sneak peek:

Maclean’s tells the story of Canadian wine from coast to coast in words and pictures in Wine in Canada: A Tour of Wine Country. Look for it on newsstands now. Or download the app now. In the meantime, here’s a sneak peek:

Since 1997, Anthony Carone has coaxed pinot noir from the ground in Lanoraie, Que., a place wholly unsuited to the notoriously temperamental grape. Every November, he prunes all but four of the winery’s 4,000 vines down to stubs. He pins the remaining four, which he selects for their ability to bear plentiful, sweeter, top-of-the-vine fruit, to the ground. He then buries each under a foot of earth. The resulting mound, he hopes, will keep the vine at a consistent -5° even as the temperature outside at times flirts with -40°.

In summer, he has the opposite problem at his winery on the northern banks of the St. Lawrence about 70 km east of Montreal. Hot, wet summers bring the threat of blight and mildew; each vine must be regularly cleaned because the thin-skinned grapes are so prone to disease. Intense heat, like that of last July when the town recorded 17 days of above-average temperatures, will burn the crop. Last year, he left the west-facing leaves untrimmed so that the grapes would be shaded from the day’s most intense sunlight.

This process yields about 2,000 litres—about 2,600 bottles—of light, airy pinot noir that’s more reminiscent of Old World French wine than its North American cousins. Production is small and, at $36 a bottle, the price is high. It won silver at the 2010 InterVin International Wine Awards.

Carone, a compact 47-year-old ball of energy with grey hair and an off-putting stare, shrugs off the wine’s steep price relative to other Quebec wines. “I’m the only one to produce a full pinot noir in Quebec,” he says from a table in his tasting room, in between bites of dark chocolate and prosciutto. “At first, everyone said we can’t do wine at all. Then it was, well, we can do whites. Then it was we can do icewines. Now we’re producing decent reds.”

He flashes that stare of his. “The target is moving,” he says.

Carone, like many Quebec vintners, tends to do things out of either doggedness or spite—fighting against climate, sometimes other producers and the prevailing belief that, well, Quebec is and will forever remain a wine-making hinterland. Quebec isn’t thought to do wine. Blueberries? Corn? Apples? Political scandals? Sure. Decent wine? Not so much.

Carone’s yearly dance with pinot noir is a somewhat exaggerated example of why this may be. When it isn’t buried under snow, Quebec is either being drenched by rain or baked by an unrelenting sun. The growing season is too short, and the downtime too long, to produce anything worth fermenting.

Yet skipping over Quebec wine is to deny the palate, for some of the province’s 100-odd wineries are producing some very respectable whites and reds.

In many ways, Quebec in 2013 is where Ontario was in the mid-’80s; strewn with disparate, stubborn winemakers eager to overcome their backwater reputation. Unlike Ontario, where winemakers benefited from promotion by the Grape Growers of Ontario wine association, Quebec has two winemaking associations that are completely at odds on how to move forward.

Grapes have grown in Quebec for centuries. When Jacques Cartier first saw Ile-d’Orléans in 1535, the mouth-shaped island in the St. Lawrence was overrun with native vitis riparia grapes. He called it Ile de Bacchus, even though the small blue grape was unsuited for wine. The province’s first winery, Côtes d’Ardoise (“slate hills”), opened in 1981 in Dunham.

Then Charles-Henri de Coussergues, an agricultural exchange student from the Languedoc region of France, arrived in 1982, bought a 20-hectare dairy farm just down the road from Côtes d’Ardoise and began making and selling wine from the premises.

Today, his is the largest winery in the province, producing upwards of 160,000 bottles of white, red and ice wine every year.

“Some producers think that if you put a fleur-de-lys on the bottle, Quebecers will buy it,” says de Coussergues, shaking a meaty finger in the air. “Ah, non. We need to know that we have competition, and it’s the world.”

The trouble is, Quebec’s 107 or so wineries can’t agree on how exactly to meet that challenge. It is a fundamentally divided industry, with the more established Association des Vignerons du Québec (AVQ) challenged by the upstart Vignerons Indépendants du Québec (VIQ), founded in 2006. Winemakers are a stubborn bunch, and there are many sticking points. But one of the main ones is certification and what varietals should and shouldn’t be part of it.

Standards are inconsistent.

Then there’s the climate. Quebec is cold. Ontario and British Columbia, less so. The crux of the argument is what, exactly, Quebec wine should be. People like Carone say Quebec will only be recognized as a true winemaking region when its wineries adopt the vitis vinifera grapes grown in Europe. The first commercial crop in Canada was planted in Ontario’s Niagara Region in 1978.

De Coussergues, along with a majority of the province’s winemakers, feel hardier grape hybrids—such as frontenac, a variety developed at the University of Minnesota expressly for cold climates—make excellent wine, and Quebec producers shouldn’t copy the Old World. “Our climate is part of our wine,” de Coussergues says. “You have to adapt to the environment you work in.”

It’s worth remembering that Ontario didn’t shake its spotty winemaking reputation by aggressive marketing alone. Many of the province’s winemakers, with the help of a federal subsidy, ripped out their hybrid vines in the late ’80s, replacing them with vitis vinifera varietals such as riesling and chardonnay. In Quebec, this would mean a back-breaking, low-yield crop like that of Carone’s, with prices to match.

In short, the province is stuck, says master sommelier and wine writer John Szabo. He says Les Pervenches, from Farnham, is “exciting,” and name-checks Quebec’s Clos Saragnat, the riesling from Domaine Les Bromes, the whites at L’Orpailleur, the late-harvest and icewines of Vignoble du Marathonien. Yet there is “little to no market outside Quebec” for the hybrids, while the climate makes the cost of producing a truly great red too high to be worth it. Quebec, Szabo says, should stick to “icewine, ice cider and a few whites.”

At the Gagliano Vineyards next door to L’Orpailleur, Alphonso Gagliano bristles at the suggestion that Quebec-friendly grapes aren’t up to snuff. “Canada can compete with California and Europe in quality, but not with the same types of grapes. It’s unrealistic,” he says.

The former Liberal cabinet minister only grows hybrids on his four-hectare winery. His tinello, a blend of frontenac and sabrevois grapes, came second out of 16 Canadian and international wines in a blind taste test put on by La Presse in April 2012. “They thought tinello was a pinot noir,” Gagliano chuckles.

A pinot from Quebec. Imagine that.