Houston, we have a sexism problem

Colby Cosh on ‘Shirtstorm’ and the fight for equality in the world of science

Share

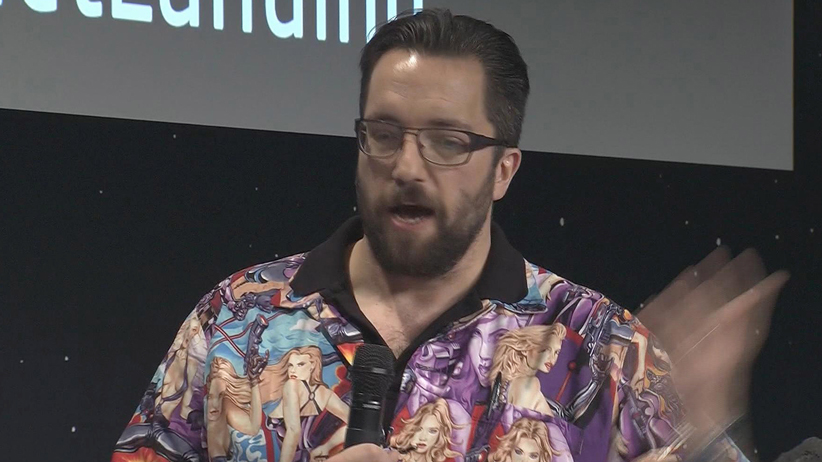

They’re calling it the Shirtstorm. The victim: Matt Taylor, a physicist from London, who is the project scientist for the European Space Agency (ESA)’s Rosetta mission to Comet Churyumov-Gerasimenko. Early in the period of the probe’s approach to the comet, he attracted favourable comment for his casual, Millennial-friendly on-camera style and appearance—in particular, a large array of colourful tattoos, which include a picture of Rosetta and her lander, Philae. Here at last, someone born in 1980 might say, is a scientist who is one of us, a scientist possibly born after slide rules went away.

At a critical moment, when it was unclear whether Philae would be able to land on the surface of the comet, Taylor’s sartorial instincts let him down. His sister describes him as very absent-minded, so it perhaps did not occur to him that his audience would suddenly grow a hundred-fold or more. He appeared on NASA TV and the web wearing a kitschy art shirt, made by a (female) friend, that was covered in pin-up-type images of half-naked blond ladies.

This did not go over well in a world increasingly sensitive to the hostilities women face in math-heavy career environments. Taylor seemed almost to be deliberately representing a heedless, unenlightened scientific patriarchy. A wave of media attacks and a tearful broadcast apology followed.

But the brief spectacle was awkward for secular liberals, who regard science as not only a superior means of knowledge acquisition, but a sacred one. The 19th-century progressive’s view of science as a sort of perpetually threatened gem-like flame that must be protected and cherished by a vanguard of intellectuals has come roaring back into vogue. This creates the conditions for self-contradiction. People got a look at a real scientist who doesn’t have a stylist on the payroll—although, were the ESA’s press people all on vacation?—and some started objecting to the semiotics of his shirt, even as his team was landing a human artifact on a comet.

Under the circumstances, not every liberal nerd seemed quite sure how to reconcile pro-science and pro-equality credentials. Taylor had fallen a little short of liberal ideals, politically. In so doing, he inadvertently raised the question of what his critics would have made of Wernher von Braun.

Just about the only egalitarian thing about the scientific enterprise is its premise that ideas and techniques will be tested without reference to the identity of their originator. In practice, science is deeply, cruelly elitist; it makes no promise that its findings will validate or encourage human equality, and its history is, from a feminist standpoint, irreparably compromised. You can read pretty damned far into the history of fields such as rocketry without encountering a female proper noun. Indeed, when it comes to rocketry, the first one you bump into might be Laika, the dog the Russians bundled into Sputnik 2.

This is not just some obnoxious coincidence or patriarchal conspiracy. If we as a species had waited for women to discover, say, hypergolic rocket fuels, we would still be waiting. They value having 10 fingers too much to have ever done the necessary experiments.

Yet I find it hard to have too much sympathy for Taylor, any more than I do for the person who puts a pound of silver jewellery in his face and complains that he can’t find a retail job. Taylor has got to have at least 24 hours’ worth of tattoo acreage. Surely, anyone who values self-expression that highly is responsible for taking the trouble to get it right? The various forms of political correctness are, in one sense, IQ tests, and this particular form of PC—the demand that women of ability be made welcome in technical workplaces—is a matter of common fairness.

Maybe you are a knuckle-dragging sexist who thinks women mostly stink at math. If so, congratulations! There’s a truckload of science-y data suggesting you might be right! But you will notice that your revolting and backward belief does not relieve the duty to accommodate the few women who can cut the mustard. It could be regarded as imposing a much greater duty. And it should not be hard to see that the list of responsibilities would naturally include: “Try not to wear a men’s magazine on your back at work.”

The white male spacefaring tradition has an established solution to the problem of how to dress at Mission Control. White shirt, black tie, G-Man eyeglasses, pocket protector. Hell, you’ve seen Apollo 13. I guarantee Taylor has. He figured he could improve on the uncool old ways: If you do that, you cannot complain about being held to the newest standards.