Tracking COVID-19’s evolving language, from ‘self-isolation’ to ‘social distancing’

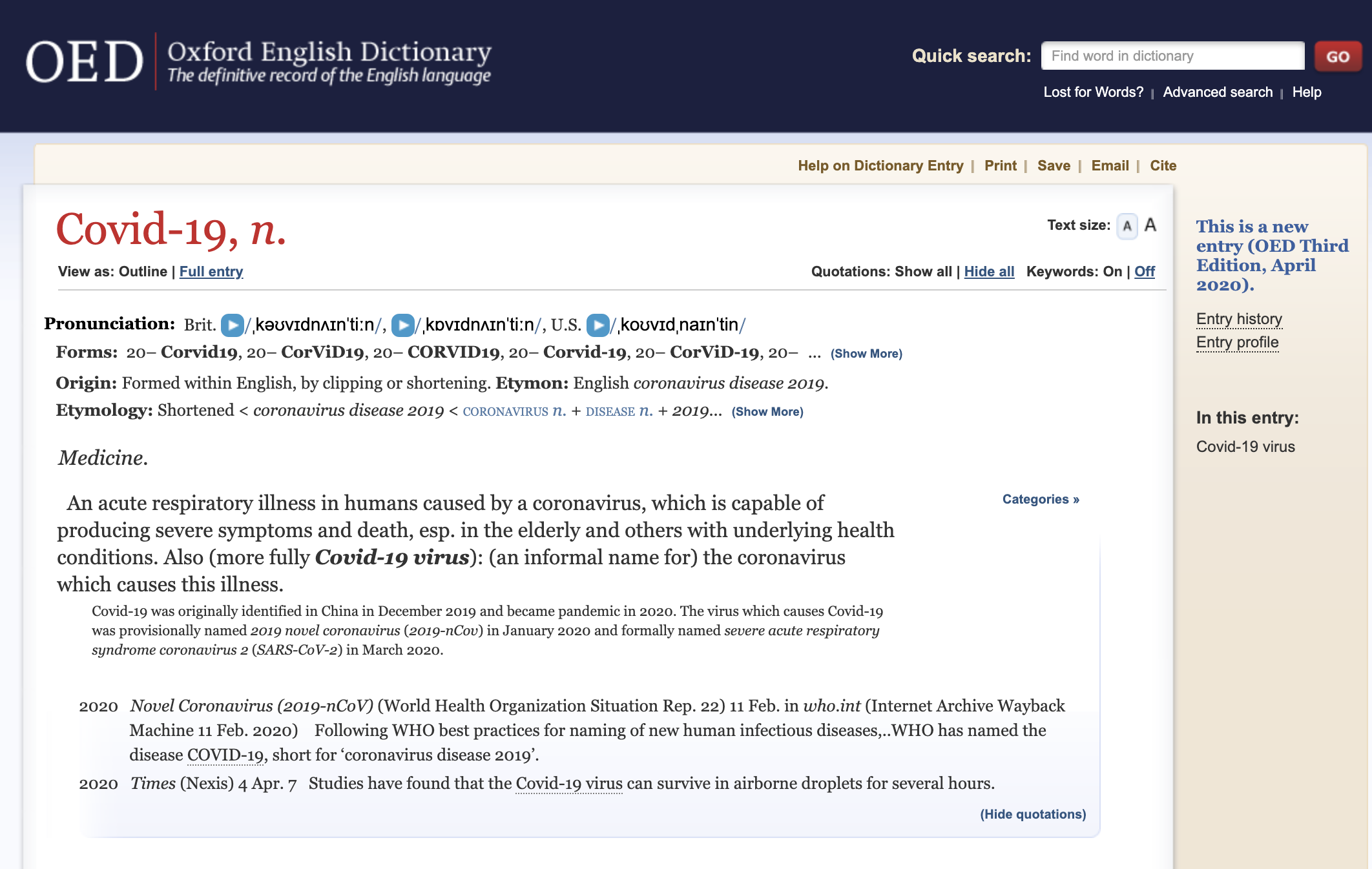

The Oxford English Dictionary is adding pandemic-related terminology to its repositories of words, including a completely new word: COVID-19 itself.

The Oxford English Dictionary webpage for Covid-19.

Share

The COVID-19 pandemic has radically reshaped the world’s vocabulary. “I find it fascinating that words which we (probably) weren’t using 3 months ago are suddenly completely normal and natural and are probably featured in the majority of conversations that we are having,” explains Fiona McPherson, Oxford English Dictionary‘s senior editor of new words, in an email interview from Germany. “I’ve often remarked that a lexicographer never sleeps in the sense that we are often highly attuned to new words, or unusual usage of existing words, popping up in discourse, on television, in books, etc. This is no different, but it would be fair to say that in these times, these words are probably on everyone’s radar.”

The speed at which the new COVID-19 vocabulary has been adopted has surprised even the experts. “It’s unusual to have words popularized in the way we are seeing in such a short space of time—normally words take longer to bed in or take hold. When something is affecting the whole world, as this is, it is understandable that this might be accelerated,” notes McPherson. The Oxford English Dictionary is always monitoring linguistic developments, and the spread of the virus through the world can be seen in its monthly lists of top 20 keywords. In January, eight were related to the pandemic; by February, that number had risen to 14, and then, in March, all 20 words were linked to COVID-19.

The changes were so dramatic that the OED rushed to add pandemic-related terminology to its repositories of words, ignoring its normal quarterly update cycle. Its list of pandemic-related words includes only one completely new word, that for the virus itself: COVID-19, short for “coronavirus disease 2019,” which was officially named by the World Health Organization.

The others were “words that aren’t used widely enough to merit inclusion in the OED,” at least until now, explains McPherson. “All words were new once, after all, and just because a word isn’t currently common enough doesn’t mean that it won’t be at some point. With these, it is perhaps more accurate to say they hadn’t crossed our collective radar until this pandemic.”

Some of the new entries are:

- Self-isolation, first recorded in 1834

- Social distancing, first used in 1957

- WFH (work from home), first used as a noun in 1994 and as a verb in 2001

- Elbow bump, from 1981

- Personal protective equipment, dates back to 1934 while the PPE abbreviation was first used in 1977

The naming of the entire event itself will take time to sink into the world’s vocabulary. One option, the Great Lockdown, was used by the International Monetary Fund for its report on the economic impact of the pandemic. Others include the Great Pandemic and World War COVID. Eventually, the OED‘s experts will find the dominant term’s first usage. For nearly a century, Maclean’s had the bragging rights for being the first publication to give the Great War its moniker, with a small reference in its October 1914 issue, just after the outbreak of what would subsequently be known as the First World War. Those “firsts” are always changing. A few years ago, Maclean’s was displaced when an early “Great War” reference was found in the July 28, 1914 issue of the Liverpool Echo.

A pandemic-related term that resonates with McPherson has a Canadian connection: “My favourite isn’t to do with a name for the situation itself, but something that has arisen from the situation. Caremongering has emerged, in Canada I believe, meaning ‘the provision of help, such as shopping, for vulnerable members of the community during the COVID-19 breakout.’ It’s a relief to focus on something positive in all the darkness.”