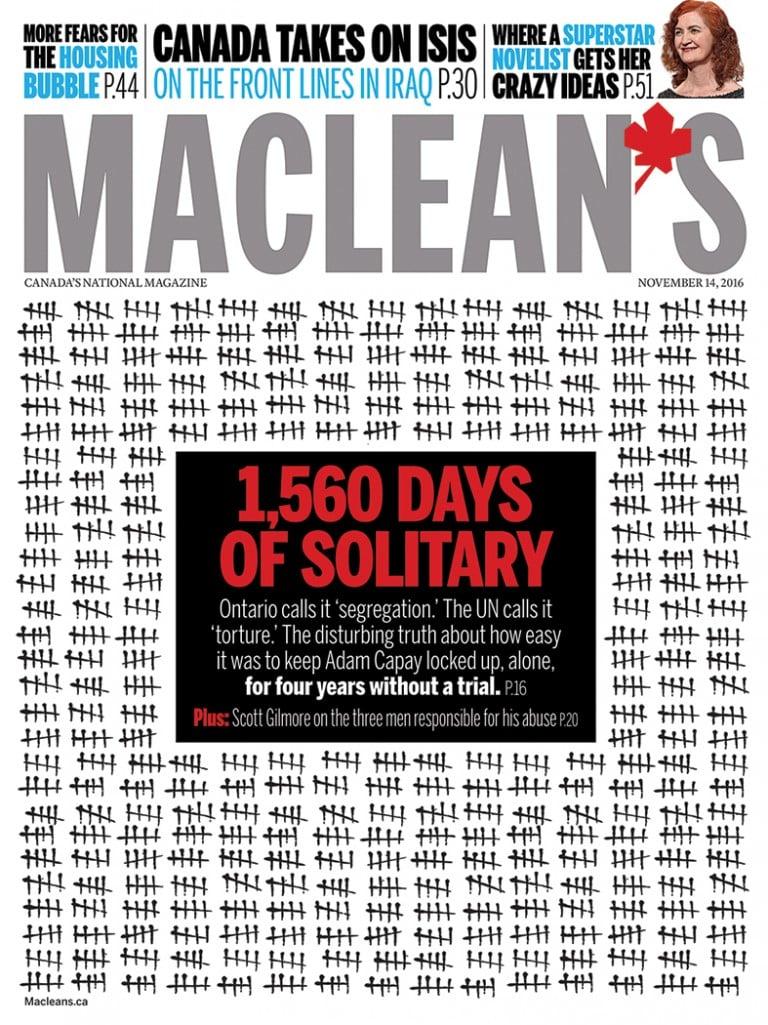

Why Adam Capay spent 1,560 days in solitary

From 2016: The UN would call Adam Capay’s treatment torture. In a Canadian prison, he was just another inmate in segregation.

Share

Renu Mandhane spent part of her day on Oct. 7 at the Indigenous friendship centre located on the outskirts of Thunder Bay, Ont. Mandhane, 39, is chief commissioner of the Ontario Human Rights Commission (OHCR), the 55-year-old body charged with preventing discrimination and advancing human rights in Ontario. Her office had organized the meeting with Indigenous leaders and community members to talk about discrimination and racial profiling.

After the meeting was over, Mandhane organized an impromptu tour of the Thunder Bay Jail, a 170-bed facility built in 1926. “It’s a s–thole,” says Mike Lundy, a union president and a correctional officer at the jail.

Mandhane toured the facility with Shaheen Azmi, a colleague from the OHRC, along with Bill Wheeler, the jail’s superintendent and Christina Danylchenko, an assistant deputy minister with Ontario’s Ministry of Community Safety and Correctional Services. A social worker and another government bureaucrat came along. Management had selected three inmates for Mandhane to speak with.

She also met privately with a correctional officer who’d reached out to her earlier. She asked him if there was anything that management wouldn’t want her to see. “Ask to see Adam Capay,” the officer said. “He’s been in administrative segregation for four years.”

Mandhane was skeptical. The statistics provided by the ministry indicated that the longest anyone had spent in segregation in the Ontario correctional system was 939 days—much less than the more than 1,500 days Capay was said to have been languishing. Under the United Nations Mandela Rules, prisoners shouldn’t be confined to their cells for 22 hours a day without meaningful human contact for more than 15 consecutive days.

She and Azmi went down a set of stairs to a windowless floor. She saw Capay through bars and Plexiglas. He was petite and thin in his orange prison jumpsuit—like a kid, Mandhane thought. His cell was about 5 x 10 feet. They spoke through a smartphone-sized hole cut out of the Plexiglas.

“How old are you?”

“Twenty-three,” said Capay. He apologized to her for speaking so slowly. He hadn’t spoken much in the last four years, and had trouble with words. He’d been in this predicament since 2012, when he was charged with killing another inmate. His trial had been delayed three times.

At the very least, the details from Capay’s 20-minute conversation with Mandhane put an end to the fanciful notion of Canada as a bastion of fairness and the rule of law. Capay said he spent much of his time in a kind of half sleep, drifting in and out of consciousness. The lights were on 24 hours a day. Reality was difficult to discern. He was constantly hungry. He went into the yard once or twice a month.

A psychiatrist talked to him for a couple of minutes every few months, mostly to approve his continued segregation. He’d engaged in self-harm, and had lacerations on his wrists and puncture wounds on his scalp. He’d recently been restrained after bashing his head against the wall.

After seeking his consent to speak about his case, Mandhane said goodbye to Capay. She and Azmi rejoined the touring group upstairs. Mandhane told the group that Capay said he’d been in segregation for 4½ years. “Yeah, that’s about right,” she remembers Wheeler saying.

Administrative segregation, in which an inmate is separated from a jail’s general population, isn’t a particularly unique practice. According to a recent OHRC report, nearly 20 per cent of the province’s roughly 21,000 prisoners served at least one day in segregation between October and December 2015. Nearly 1,500 spent more than 15 days.

The shocking aspect of Capay’s case isn’t just the sheer length of time spent in near-solitude, or that it went on with the apparent knowledge of the facility’s senior management. It’s not only that every five days of segregation was meant to lead to a review of his situation, or that every 30 days of Capay’s windowless misery was meant to prompt a formal report to senior bureaucrats in Ontario’s Correctional Services, or that those very bureaucrats would have again been notified when Capay spent more than 60 days in a 12-month period—meaning upper bureaucratic ranks were, theoretically, alerted of Capay’s plight well over 50 times.

It’s that Capay was there ostensibly for his own protection. This wasn’t punishment. According to Ontario’s Correctional Services, inmates are placed in administrative segregation when they are in need of protection, pose a threat to the health and safety of themselves or others, or are alleged to have committed a serious misconduct. “In Canada, we do not practise solitary confinement,” a Public Safety Canada official, Kimberley Lavoie, told a UN meeting in Geneva on Oct. 25, a week after Mandhane revealed Capay’s plight.

Capay’s life on the reserve of Lac Seul in northwestern Ontario was seemingly stable. He is the eldest of six brothers and sisters. His father is a home care worker; his mother works for the band council. Yet his teenage and early adult years were marked by difficulty and sometimes violence; there were well over a dozen charges against him, ranging from loitering to uttering threats to assault. He spent five weeks in jail following an assault charge from an incident on New Year’s Day 2012. On Feb. 23, he was again arrested and later charged with mischief, weapons possession and breaching probation after damaging his mother’s car. In total, Capay pleaded guilty to five charges, and was given a five-month sentence.

In the early hours of June 3, 2012, Capay allegedly fought with Sherman Quisses, a 35-year-old inmate, in the dorm-style room of the Thunder Bay Correctional Centre. According to court filings, Capay used a sharp instrument to puncture Quisses’s carotid artery. Quisses, a father of one from a northern Ontario reserve, died the next day. Capay was charged with first-degree murder, and moved to the Thunder Bay Jail.

He has been in purgatory ever since. He was first set to stand trial in September 2014, but it was delayed after Ryan Amy, Capay’s lawyer at the time, filed a motion questioning the impartiality of the jury due to its racial makeup. A second trial date 11 months later was adjourned, after Amy questioned his client’s ability to stand trial. Amy brought up his client’s self-harming—by then, Capay had cut himself and hit his head against the walls of his cell—and his difficulty in speaking while in segregation.

A third trial date, in September 2016, was pushed off again after Capay dismissed Amy as his counsel. Capay will next appear in court on Nov. 28 to set a court date. Last summer, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled that a “reasonable delay” in getting to trial is 30 months. Already, Capay has been in segregation for 48.

Yasir Naqvi, the minister in charge of Ontario’s jails at the time, visited the Thunder Bay Jail on Jan. 13, about a month after an incident that saw a correctional officer taken hostage. According to Lundy, Naqvi met Capay and was informed about the prisoner’s status. Naqvi is an able politician with a knack for remembering birthdays and anniversaries of his constituents. Despite this, he told reporters that he has no recollection of the meeting—even though Lundy remembers specific details of the exchange. “He was wearing dark blue jeans and black dress shoes,” says Lundy, who added that he thought Naqvi was a good minister.

(Naqvi, who is now Ontario’s attorney general, wouldn’t comment specifically about Capay. “Our government takes the concerns that are being raised very seriously. We know that the corrections system, including the use of long-term segregation, requires transformation,” he told Maclean’s.)

Capay has been in segregation for more than four years at the Thunder Bay Jail. Despite this, his name never appeared in formal ministry statistics that correctional institutions file with the ministry. Wheeler, the superintendent, didn’t respond to an interview request. Andrew Morrison, an Ontario Correctional Services spokesman, said the ministry is “reviewing current data collecting practices.”

The exact definition of Capay’s incarceration, meanwhile, remains somewhat unclear. The United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners—better known as the Mandela Rules, after political prisoner and eventual South African president Nelson Mandela—define solitary confinement as “the confinement of prisoners for 22 hours or more a day without meaningful human contact.” These rules specifically prohibit “prolonged solitary confinement.” (Mandela himself once referred to solitary confinement as “the most forbidding aspect of prison life.”)

During Mandhane’s visit, Capay told her that he often spent 24 hours a day in his cell, despite theoretical access to a day room. The lights were never shut off, because of safety concerns due largely to Capay’s self-harm. He received occasional visits from his family; other than that, human contact has been limited to the correctional officer on duty, the visits from the psychiatrist and the disjointed voices from prisoners in the cells beside him.

Yet as Kimberley Savoie reinforced to the UN, Canada is adamant it doesn’t practise solitary confinement. “Please note that the term ‘solitary confinement’ is not accurate or applicable within the Canadian penitentiary system,” says Correctional Services Canada spokesperson Avely Serin. Canada does, however, practise “administrative segregation.” “It is the separation, when specific legal requirements are met, of an inmate from other inmates,” explains Serin.

The difference between the two is often lost on government. In 2013, Ontario’s chief coroner’s office published the findings of its inquiry into the death of 19-year-old Ashley Smith, who killed herself at a federal corrections institution after more than a year in isolation. In the report, the coroner specifically refers to “the effects of long-term solitary confinement on the inmate population.”

In the Thunder Bay Jail, which is run by a provincial government, a similar reticence to use the term “solitary confinement” exists. Capay is housed in one of seven “special handling units” that have limited access to a day room equipped with a phone.

There are two similar units, though with no access to a day room. These are reserved for prisoners who have been separated for various offences, including things like repeatedly hitting the prison bars and throwing urine and feces. Here, “Folks are not expected to spend their full incarceration period,” says the Ontario Correctional Services spokesperson Morrison—though Lundy says inmates are sometimes “left in there for months.”

In both cases, Ontario corrections officials and prison staff refer to the jail’s special handling units and the separate cells as “segregation,” not “solitary confinement.”

No matter the name attached, the psychological effects of relative isolation are well documented. “Solitary confinement does one thing: it breaks a person’s will to live,” BobbyLee Worm said in 2013 after spending 3½ years in segregation at the Saskatchewan Penitentiary. The Indigenous woman, incarcerated on robbery charges, was punished for fighting with other inmates and prison staff. Some days, the only human contact she’d had was when a small slot in the door opened and a guard passed her a tray of food.

“You feel like you’re losing your mind,” says Worm. “Days turn into nights and into days and you don’t know if you’ll ever get out. The more time I spent in solitary confinement, the more trouble I had in prison. They told me solitary confinement would help me but it made me even worse.”

Worm was under “management protocol,” a super maximum designation allowing inmates to be held indefinitely in segregation; when it was quietly ended in 2011, 100 per cent of inmates so designated were Indigenous.

Among them was Kinew James. The 35-year-old Anishinaabe from Manitoba died Jan. 20, 2013, while incarcerated at Saskatoon’s Regional Psychiatric Centre, apparently from heart failure. A few months shy of being released, James had been incarcerated since the age of 18 (initially sentenced to six years for manslaughter, her sentence doubled as she suffered mental health issues in prison and lashed out). Six of her 15 years in prison were spent in isolation. Sometimes she was held in barren cells so small she could touch the walls on either side of her. She was there 23 hours a day. At one point she spent almost two years straight in segregation, sometimes so starved for human contact she would lie against her cell floor, her face pressed against the crack beneath the door.

After prolonged stays in segregation James would sometimes “see things, hear things,” and get lost in fantasies, newly appointed Sen. Kim Pate, former executive director of the Canadian Association of Elizabeth Fry Societies, told Maclean’s last spring. “There is ample evidence Kinew’s death was preventable,” says Pate. “It screams out the need for oversight and accountability for corrections.”

Capay’s case speaks to another troubling trend in Canadian prisons: Indigenous offenders serve much harder time than anyone else. Indigenous inmates are placed in minimum-security institutions at just half the rate of their non-Indigenous counterparts. They are more likely to be placed in segregation, accounting for 31 per cent of cases; once in isolation, they’ll spend 16 per cent more time there. They account for 45 per cent of all self-harm incidents, and one-third of suicides. Nine in 10 are held to the expiry of their sentence, versus two-thirds of the non-Indigenous inmate population. They are more likely to be restrained in prison, to be involved in use-of-force incidents, to receive institutional charges, to die there.

“There is a group in Canada that keeps mysteriously dying,’” says University of Toronto sociology professor Sherene Razack. Many of these deaths occur because officials “will not touch, examine, or closely monitor Indigenous people in their care,” Razack says. “This indifference kills.”

Adam Capay’s treatment has drawn condemnation from all corners—including the very people responsible for his care. “I’m very troubled by it. It’s very disturbing and shouldn’t happen,” Ontario Premier Kathleen Wynne told reporters. Correctional Services Minister David Orazietti is “concerned for Capay’s safety,” and has said that Capay has been moved to another cell “with appropriate lighting and access to day rooms.” Lundy has said Capay’s move is temporary, and will be brought back to his cell following renovations.

His trial will likely not begin until early next year, by which time Capay could have spent another 60 to 90 days in solitary. Capay’s lawyer, Anthony Bryant, has filed an application asking the court to review the circumstances of Capay’s pre-trial detention. In turn, this may figure into his sentence should he be convicted of Quisses’s murder. Capay’s years in misery could secure him an earlier release.

—with Nancy Macdonald