Big Gulp: Republican insiders try to save the party from itself

The GOP needs to rethink outreach in order to stop “secular socialism”

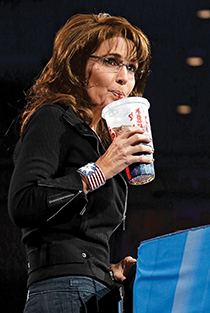

Jonathan Ernst/Reuters

Share

As the speakers revved up the crowd with jabs at Barack Obama, socialists and the “liberal media,” last week’s gathering of American conservatives at the annual Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC) felt on the surface just like any other. The convention hall near Washington teemed with banners (“Stand with Rand!”), buttons (“Don’t tread on my gun rights”) and booths that ran the conservative gamut from the Ayn Rand Committee for Individual Rights to Christians United for Israel.

But what started out as a moment of indecisive post-election soul-searching by conservative activists from around the country was only days later overshadowed by a bold move by Republican party insiders in Washington bent on saving the party from itself. To some it looked like a coup.

No sooner had the speakers and activists packed up and left town after their weekend meeting, then the chairman of the Republican National Committee, Reince Priebus, ventured into enemy territory, the National Press Club, to unveil a 100-page post-mortem report on the November election losses, and announce the party’s future strategy. The rank and file may have spent three days debating the way forward, but the party leadership had already made up its mind.

At every level, it was a striking evolution for the party from this time last year, when candidates were trying to out-conservative one another. At the last CPAC gathering, just one year ago, presidential hopefuls had come to burnish their conservative credentials in the midst of a Republican primary that had become a contest about ideological purity. It was to this crowd that Mitt Romney, who brought universal health insurance to Massachusetts, proclaimed that he had been a “severely conservative governor.”

Then Romney lost his bid for the White House; Republicans failed to take the U.S. Senate; and their majority in the House of Representatives shrunk. So when some 3,000 conservatives gathered last week, there was plenty of blame to go around: at Romney, at the campaign consultants, at party policies, and at those Tea Party-ish candidates who said offensive things about rape. They held panel discussions with names like, “Too many American wars?” and, “Should we shoot all the consultants now?”

Out of the speeches and discussions came two pressing questions: should the party get on board with attempts by a few Republicans, led by Florida Sen. Marco Rubio, to work with Obama and Democrats to pass comprehensive immigration reform—including some form of legalization, if not full citizenship, for the estimated 11 million undocumented immigrants? And should the party take a new approach to gay rights to stop alienating young voters who see it as the civil rights issue of their time? The party’s platform, adopted last summer, calls for a constitutional amendment banning gay marriage and reinstating the “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy for gays in the military. The platform opposed “any forms of amnesty” for undocumented immigrants. Now the conservatives were being implored to change those positions in order to achieve other goals such as limiting government spending and regulation. The debate over immigration and gay rights at times pitted the new generation of upcoming presidential hopefuls, such as Rubio and Kentucky Sen. Rand Paul, against other big names in the conservative movement, such as Sarah Palin, Donald Trump, and social conservatives such as Rick Santorum.

“If we are going to stop the tide of secular socialism, we need more allies,” Republican pollster Whit Ayres told the conference. Noting that Republicans had lost the popular vote in five of the last six presidential elections, he argued that without attracting the rapidly growing Hispanic and Latino population, Republicans are doomed. Ayres argued for aggressive Hispanic outreach and an embrace of immigration reform. “We have got to have a different message and we have got to have different messengers,” said Ayres, who advocated the nomination of Rubio, a Cuban-American, as presidential candidate. “I am absolutely convinced that we are only one candidate and one election away from a resurrection.”

Calling Hispanics “entrepreneurial, family-oriented, and church-going,” Ayres said they are a natural constituency for Republicans—but are turned off by rhetoric such as Romney’s advocacy of “self-deportation” of undocumented immigrants. He noted that George W. Bush, who used more inclusive language, had won 44 per cent of the Hispanic vote, while Romney got only 26 per cent. “The notion that we can use harsh tones against undocumented immigrants and not offend Hispanics is delusional,” said Ayres. “We’ve got to get it right on immigration before they’ll listen to us on taxes or the economy or anything else.”

When it was his turn to address the crowd, the popular Rubio did not talk about immigration, but about appealing to middle-class voters courted by Obama. He argued that the public has come to see the Republican party as “fighting for the people who have made it,” rather than fighting for ordinary Americans.

The other star of the day was Sen. Rand Paul, a libertarian who staged a 13-hour filibuster of Obama’s nominee to head the CIA, protesting the secrecy around Obama’s targeted killings of terrorist suspects abroad—that have included American citizens. “If we allow the President to drone citizens, what have our brave men and women been fighting for?” said Paul, to applause. “The GOP of old has grown stale and moss-covered. The new GOP will have to embrace liberty in both the economic and personal sphere.”

Rand won the gathering’s presidential straw poll; Rubio came a close second.

But not everyone wanted to hear messages of change.

Real estate mogul Donald Trump criticized the emphasis on legalizing undocumented immigrants. “If given the right to vote, every one of those 11 million people will be voting Democratic,” he told Republicans. “You are on a suicide mission. You’re just not going to get those votes.”

Former Alaska governor and Tea Party darling Sarah Palin took a similar tack: “We are not here to rebrand a party, we are here to rebuild a country. We’re not here to dedicate ourselves to new talking points coming from Washington.” She quoted Margaret Thatcher and advised conservatives not to “go wobbly on their beliefs” after losing an election.

Long-time conservative activist Phyllis Schlafly also stood against the attempts to rebrand the party by the Washington establishment: “The fight we have, and the fight I want you to engage in, is the establishment against the grassroots. The establishment has given us a whole series of losers. Bob Dole and John McCain. Mitt Romney.”

In the corridors of the convention hall, rank-and-file Republicans voiced concern about the divisions. “There is no general vision within the Republican party that you can get on board with. It’s a bunch of different conservative groups, a lot of individual causes,” said Olivia Bryan, a 22-year-old student from Pensacola, Fla., who worried about a “lack of party unity.”

Brandon Standish, a 30-year-old customs broker from Buffalo, was critical of organizers for excluding a gay conservatives group from the meeting. “They need to move away from divisive messages on gay marriage and toward more practical arguments, especially on spending,” he said. “If you are serious about growing the party, you have to include everybody.”

It was clear the election defeat was causing rethinking in the ranks, and the immigration message was beginning to sink in. “I’m as conservative as it gets, socially and fiscally,” said Brady Cremeens, a 22-year-old student from Hopedale, Ill. But the election loss has caused him to rethink positions on immigration reform. “I’ve become more open to ideas on that,” he said, referring to Rubio’s immigration plan. “We’ve got to reach out to those communities,” said Cremeens. “There is a battle within the movement.”

But while the speakers and the activists thought they were having a battle, or at least a debate, their leaders had already made up their minds.

The detailed strategy document released by Priebus on Monday took a hammer to any Palin-esque notion of looking for “wisdom” among the grassroots. His strategy was based on precisely those things the traditionalists rail against: focus groups and polls. The language was searing: “Public perception of the party is at record lows. Young voters are increasingly rolling their eyes at what the party represents, and many minorities wrongly think that Republicans do not like them or want them in the country. When someone rolls their eyes at us, they are not likely to open their ears to us.”

The report suggested a range of reforms, from the recruitment of minority candidates, to setting up in Silicon Valley to tap high-tech talent, to creating an internal data-analytics institute to crunch numbers about voters to match Obama’s refined approach.

But it was more than that. The report was a blunt retort to the notions voiced by numerous speakers at CPAC that conservatives need only cling harder to their principles. “We have become expert in how to provide ideological reinforcement to like-minded people, but devastatingly, we have lost the ability to be persuasive with, or welcoming to, those who do not agree with us on every issue,” the report states.

It accused Republicans of “driving around in circles on an ideological cul-de-sac,” and declared: “Our standard should not be universal purity; it should be a more welcoming conservatism.”

Latino outreach was a big piece of the picture, echoing the kinds of arguments that Ayres had made to CPAC. From embracing immigration reform, to building a database of Hispanic leaders, to establishing “swearing-in citizenship teams to introduce new citizens after naturalization ceremonies to the Republican party.”

(As if on cue, the following day, Sen. Rand Paul embraced a pathway to legalization for undocumented immigrants, something that would have been unthinkable in last year’s GOP race. “Immigration Reform will not occur until conservative Republicans like myself become part of the solution,” Paul said in a speech to the Hispanic Chamber of Commerce. “I am here today to begin that conversation.”)

And Priebus’s strategy document included a shift in tone on social issues as well. It said that for the young voters the party needs to attract, gay rights issues are “a gateway into whether the party is a place they want to be.” Dovetailing with the party’s new desire to include a diversity of views, former Bush budget director and senator from Ohio, Rob Portman, became the first sitting Republican senator to come out in favour of gay marriage. Portman made his announcement last week, explaining that his college-aged son had come out to him. On Monday, party chairman Priebus said Portman was a “good, conservative Republican” and that the GOP would continue to support him—and that Portman’s announcement had made “some pretty big inroads” with the gay community.

And as if that wasn’t enough overhaul, Priebus called for another controversial move: he wants to cut the number of debates in half and get primary votes and the party convention over much earlier in the election year. Such moves favour big-name, well-financed candidates over upstarts with strong grassroots support, like Rick Santorum, who gained momentum toward the end of the debates, bolstered by support from evangelical Christians and home schoolers.

Social conservatives responded to the report with uproar. Christian activist and former presidential hopeful Gary Bauer warned that the party leadership is taking its evangelical base for granted. “I believe they are clueless to how close the party is to losing the energy and the votes of its largest voting bloc, which are values conservatives,” Bauer told the National Review. “What we shouldn’t do is say to the electorate, ‘Just tell us what you want us to be! We’ll change for you! Just tell us what you want us to do, we’ll do it!’ ” he adds. “That’s not a political party, that’s just a bunch of pandering idiots.”

But if the leadership has its way, the in-house battle may be over just as the rank and file think it is getting under way.