Could Trump launch nuclear war?

If elected president, yes. The U.S. commander in chief has complete and total control over America’s 1,538 nuclear warheads.

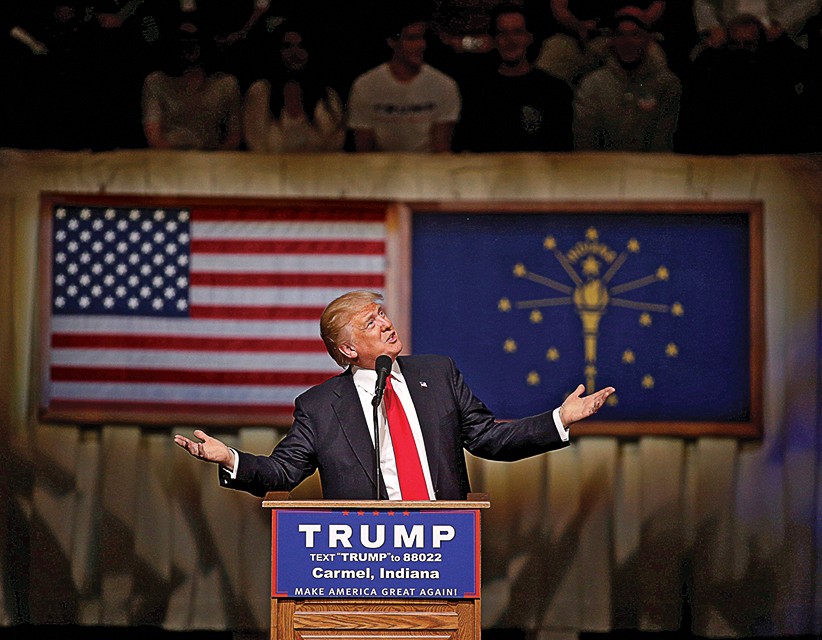

U.S. Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump speaks at a campaign event at The Palladium at the Center for Performing Arts in Carmel, Indiana, U.S. May 2, 2016. (Aaron Bernstein/Reuters)

Share

In her speech at the Democratic National Convention, Hillary Clinton questioned whether Donald Trump has the temperament necessary to control the United States’ nuclear arsenal, which can kill hundreds of millions of people at the press of a button. She pointed to his erratic behaviour and flashes of anger when provoked by opponents or reporters on the campaign trial. “A man you can bait with a tweet is not a man we can trust with nuclear weapons,” said Clinton.

But just how worried should the world be about a President Trump with his finger on the nuclear trigger? Surely in the United States, with its many checks and balances on the levers of power, there would be some safety checks in place?

In fact, control of deployed nuclear warheads—all 1,538 of them—are entirely at the whim of the president, with nothing standing in the way of an order from the commander in chief to fire away. The reason has to do with timing. Nuclear weapons launched from China or Russia take about 30 minutes to reach the White House; those coming from submarines in the Atlantic Ocean can take as little as 12 minutes. If a nuclear strike against the U.S. is detected, the president identifies him or herself using a code on a small plastic card that’s with him at all times—nicknamed “the biscuit”—and can order bomber pilots and rocket crews to launch the warheads, each with 10 to 20 times more power than the Hiroshima bomb.

Even if the U.S. isn’t under attack, the president can act if they feel there is a threat of “imminent” attack—practically, this means the president can deploy whenever they want.

In an interview on the Today show on April 28, Trump said: “I will be the last to use nuclear weapons. It’s a horror to use nuclear weapons. The power of weaponry today is the single greatest problem that our world has.” But in that same interview, he also said he wouldn’t rule out using nuclear weapons against Islamic State because he wants to maintain “unpredictability”. This week, MSNBC anchor Joe Scarborough said that Trump asked a foreign policy adviser three times in the span of an hour why the U.S. can’t use nuclear weapons. (Trump’s campaign denied the report.)

Trump’s unpredictability is what scares so many experts, especially considering the only mechanisms in place to countermand a presidential order to deploy nuclear weapons veer close to a coup d’état—generals can refuse to carry out the president’s orders or the Cabinet can declare the President unfit in a letter to Congress and hand authority to the vice president. Neither of these options are realistic when a president has minutes to decide whether to deploy in response to incoming missiles.

At a debate during the Republican primaries on Dec. 15, Trump said: “The biggest problem we have is nuclear—nuclear proliferation and having some maniac, having some madman go out and get a nuclear weapon.” Trump does not, of course, see himself as that madman. But plenty of others do. Nuclear security expert Bruce Blair wrote a 6,600-word piece for Politico arguing that Trump’s tendency towards hardball negotiation tactics relying on bombast and threats could lead to disaster. Dozens of military and foreign policy heavyweights, including President Barack Obama, have blasted Trump’s nuclear statements as dangerous and flying in the face of 70 years of policy based on limiting the number of countries that have nuclear weapons.

In addition to Trump’s judgement, they object to his trashing of the 70-year consensus on how to conduct nuclear policy. Trump is open to South Korea, Japan and Saudi Arabia getting nuclear weapons if it means the U.S. can spend less on protecting them. That policy shocks foreign policy experts on the right and the left but it plays well with many voters. Trump is pointing to the billions of dollars spent maintaining the United States’ nuclear arsenal and the 147 countries the U.S. sent special forces to in 2015 and asking the question—why are Americans paying for this?

What may be most alarming is that Trump appears to lack a basic understanding of how American nuclear defence works. In a Republican primary debate in December, Trump was asked whether he had a priority among “the three legs of the triad.” Trump gave a rambling answer in which it was clear he didn’t know what the nuclear triad was. Marco Rubio promptly identified the triad as the three ways in which the U.S. primarily deploys nuclear weapons: by bomber, submarine, or intercontinental ballistic missile.