GOP convention: Fear of turmoil stirs memories of 1968

A Canadian politician remembers an annus horribilis, as shades of the Democrats’ 1968 convention re-emerge

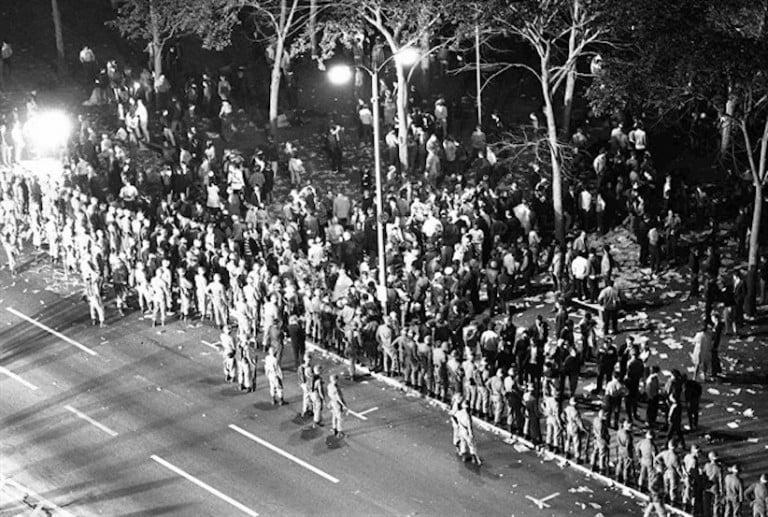

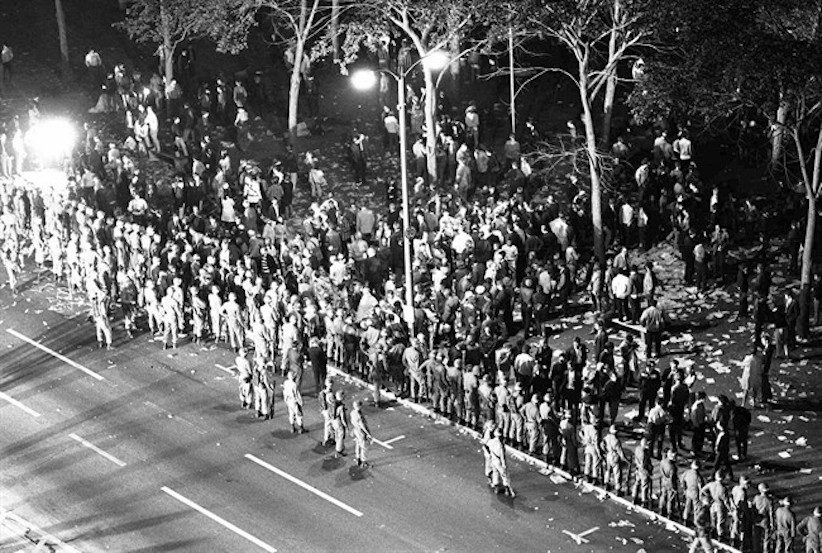

National Guardsmen lining the street as they are confronted by protesters in front of the Conrad Hilton Hotel in Chicago, headquarters for the 1968 Democratic National Convention on Aug. 28, 1968. THE CANADIAN PRESS/AP, File

Share

CLEVELAND – Warnings of potential unrest at this week’s Republican convention have stirred up melancholic childhood memories for one Canadian politician.

Elizabeth May remembers 1968.

The tectonic forces of a divided society slammed into each other on the streets of Chicago and she not only witnessed the violent effect, which overshadowed the democratic president-picking process — she smelled and tasted it.

“I was tear-gassed,” the Green party leader recalled in an interview.

“It was a deeply horrible experience.”

It was a deeply horrible year, in several respects. Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy were assassinated two months apart; black neighbourhoods were torched in riots; it was the deadliest year in Vietnam, with 16,899 Americans killed. Anti-war protesters gathered at the ruling Democratic party’s convention, and police responded with a skull-bashing force later deemed by a federal study to have been unprovoked, excessive and indiscriminate.

Around this year’s convention site, some residents are concerned. Will Cleveland 2016 follow Chicago 1968 into the political vocabulary? One homeowner said she happily accepted an invitation to visit friends out of town: “Everyone who lives near downtown is feeling kind of nervous.”

A combustible recipe is coalescing in Cleveland.

White nationalists and a black power group have both told media they intend to be there. Black Lives Matter protesters say they will also be attending, although their national organizers won’t be. Progressives and homophobes from the Westboro Baptist Church; Latino groups and Republicans who want a southern border wall and deportation — they’re all in the mix.

Another ingredient is guns.

Ohio is among several dozen states allowing the open carry of firearms. A leader of the New Black Panthers group says his members might be packing, if it’s allowed. An organizer for Bikers for Trump says he fears the event degenerating into “the O.K. Corral.”

Authorities have prepared by sending in several thousand federal agents. Cleveland-area jails have been cleared to make room for detainees. Motorists will be subject to checkpoints and magnetic car searches. And a fenced perimeter will keep protests away from Quicken Loans arena, where Donald Trump is to accept the Republican nomination Thursday.

“I am concerned about the possibility of violence,” Jeh Johnson, the secretary of homeland security, told a congressional hearing when asked about the Republican and Democratic conventions.

Add recent events in Dallas, Louisiana, Minnesota, and Paris — with shootings involving police, and terrorists targeting crowds, and it’s a modern-day mutation of two old strains that plagued 1968. Racial division. Far-reaching unrest, linked to distant conflict.

May still chokes up when discussing events of that spring and summer.

Her voice quivers while describing how she heard of King’s death as a 13-year-old girl growing up in Connecticut, and sobbing in the bathtub. She pauses again as she recalls seeing her parents’ tears by the light of the TV on the night Kennedy died.

Her parents responded differently to those events: “My dad, who was British, kept saying, ‘I think it’s time to leave this awful country.'” Her mom Stephanie was determined to change things at home; she became one of the delegates for the anti-war presidential candidate Eugene McCarthy.

That’s how May wound up at the convention.

She only managed to enter one day, so she missed most of the inside events — including McCarthy delegates protesting their party through song, drowning out calls for order after a tribute to the late Kennedy by dragging out a 22-minute version of the “Battle Hymn of The Republic,” with its famous chorus, “Glory, glory, hallelujah, his truth is marching on.”

The most searing memory occurred the afternoon of Aug. 28 — the day a peace resolution was blocked from the party platform. May was in a different part of town, watching sailboats on Lake Michigan while people played softball in Grant Park by the waterfront. In her recollection, nobody was protesting.

Then the National Guard rolled in, in khaki-coloured vehicles ringed with barbed wire. She recalls local police following, swinging billy-clubs. A cloud of tear gas stung her eyes, her airway, and in the mouth around her braces.

“They forced us into a smaller and smaller area until they began breaking heads… I fled with (other delegates’ families). If we hadn’t had hotel keys to prove we were at (a nearby) hotel we wouldn’t have been allowed in.”

She recalls yelling at the National Guard: “Is this Czechoslovakia?” That’s another event from early 1968 — democracy demonstrations in Prague, followed by a bloody Soviet crackdown.

The chaos of that convention prompted the major parties to democratize their nominating process, with the modern-day primary system.

May says it’s hard to compare the current climate with events back then.

In some ways, she says, the country is worse off — in terms of income inequality, for instance. On the other hand, she says, Americans aren’t involved in an “illegal” mass-casualty conflict like Vietnam; the country has an African-American president; Obama hasn’t behaved like “a despot” like Lyndon Johnson; and today’s Cleveland doesn’t have a party-boss structure like the Chicago of 1968, where mayor Richard Daley used police to silence dissent.

Police also promise a different approach this week.

Cleveland deputy chief Edward Tomba recently summed it up as: “Community policing. Community engagement.”

Officers will be dressed in short-sleeved shirts and will be riding around on bicycles, horses and motorbikes. “What you won’t see is any military-style equipment. You won’t see officers in personal protective gear.”

He added: “Unless the situation dictates that they put on that gear.”