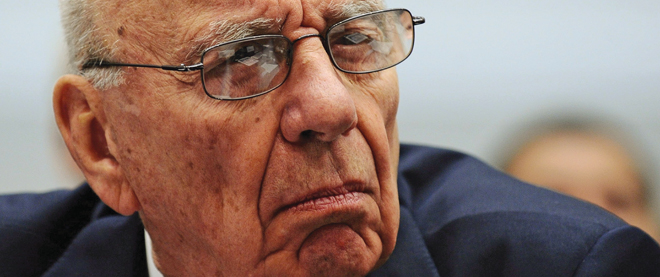

Rupert Murdoch’s day of reckoning

For Murdoch, the benefits of being highly successful outweighed the costs of being deeply unloved

Share

The most telling story in Michael Wolff’s biography of Rupert Murdoch, The Man Who Owns the News, didn’t appear in the original 2008, 400-plus-page hardcover. It’s the tale of the media mogul’s reaction to the book, appended as a forward to the paperback version two years later. Eight weeks before the first edition hit the streets, the News Corporation proprietor somehow obtained a copy—“purloined,” writes Wolff, from a rival British newspaper that was bidding on the serialization rights. And as he read the product of the more than 50 hours of candid and profane interviews he had given, Murdoch got upset. Over the course of a single day, he left the author a dozen increasingly agitated voice mails, quibbling with ancient details, and complaining about tone and interpretation. Then he went ominously silent.

For three months after its publication, Wolff’s book received exactly zero mentions in, or on, News Corp.’s globe-spanning network of media properties, which includes the Australian, the U.K.’s Sun, the Wall Street Journal and Fox News. Then the Murdoch-owned New York Post splashed news of the fiftysomething “bald, trout-lipped” writer’s extramarital affair with a 28-year-old “hot blond” intern all over its gossip pages. For weeks, the Post kept at it, chronicling his crumbling marriage, accusing Wolff of trying to evict his 85-year-old mother-in-law from an apartment he owned, even lampooning him in highly unflattering editorial cartoons. The attacks only ceased when he threatened to post the recordings of his interviews with the paper’s owner on the Internet, in all their unedited glory.

For the author, the painful episode confirmed something he already knew—scandal and bullying are both Murdoch’s trade and passion. The obsession is partly about gathering business intelligence, Wolff writes in his forward: “who is saying what to whom; who might be buying what; who has less money than he says he has.” But the 80-year-old titan also just really delights in the dirty details. “He especially likes to know which liberals are sleeping around (but he will take conservatives, too). It is a prurient interest, but it is also about leverage. He refers to having pictures and reports and files.” At the time, Wolff assumed such claims were part of Murdoch’s trademark hubris, designed to fuel his cultivated image as a villainous billionaire. Now it appears they may have simply been the truth.

In the course of two weeks, a phone and data hacking scandal that has been unfolding in dribs and drabs for more than five years has gone nuclear, threatening to engulf both Murdoch and his media empire (page 28). A British public that seemed unfazed—or at best bemused—with the idea that its press were snooping through the voice mails and records of royals, footie stars and reality TV contestants has become outraged that such privacy invasions were also committed against the victims of murder and terror attacks, and the families of dead soldiers.

News Corp.’s decision to shutter the 168-year-old News of the World, the Sunday tabloid that was responsible for the bulk of the offences—and the most popular newspaper in Britain—has done little to stem the backlash. Andy Coulson, the paper’s editor from 2003 to 2007 and, until this past January, Prime Minister David Cameron’s director of communications, has been arrested. So has Clive Goodman, its former royals correspondent. Scotland Yard is said to be probing allegations that a senior company executive purged “millions” of archived emails in an attempted cover-up. There are also parallel investigations into disclosures that the News of the World routinely paid London police for information, and scored top secret documents about the royal family from the officers charged with protecting them. New hacking victims are emerging on an almost hourly basis: most notably former PM Gordon Brown, who had his bank, property and tax records stolen, and saw the serious illnesses of his children—with details culled directly from their medical files—turned into fodder for two other News Corp. publications, the Sun and the Sunday Times. Calls for an immediate public inquiry into the phone hacking, as well as the general conduct of the British press, are growing.

But perhaps most significantly for Murdoch, the bad publicity is hurting the bottom line. News Corp. stock has dropped by more than US$2.50 per share in the course of a week, which translates to more than $5 billion in market value. And an $18.5-billion bid to assume full control of Britain’s BSkyB satellite channel, which was all but approved by the government, has been kicked back for a full competition office review, potentially delaying the deal for years. (BSkyB shares plummeted more than 15 per cent in a week, shaving more than $4 billion off that corporation’s market value.)

And after decades of running his publicly traded media company like a private fiefdom—the Murdoch clan collectively own less than 40 per cent of News Corp. common stock—the patriarch suddenly finds himself in a precarious position. Festering shareholder discontent over a series of expensive flops, like the 2005 US$580-million acquisition of MySpace, sold earlier this month for just US$35 million, and the $5-billion takeover of the Dow Jones and the Wall Street Journal, threatens to worsen. Plans to transfer power to his youngest son James, recently elevated to News Corp.’s number three job as deputy chief operating officer, look dubious as the 38-year-old tries to contend with a scandal that happened on his watch as the head of U.K. operations. And the old man’s legions of enemies and detractors are exulting in the possibility that he might finally get his comeuppance. Not to mention the politicians he has long terrorized. “The hacking scandal throws up an array of insights. But one in particular stands out to liberals: information is power. It always has been,” Nick Clegg, leader of the Liberal Democrats and the U.K.’s deputy prime minister, wrote in a blog post this week. “When elites deploy secretive and opaque practices, it is nearly always to protect their own position. And when you reveal those secrets, you rock the foundations of the powers that be.” For close to a half-century, Rupert Murdoch has been shaping the news. Now, the news is shaping him.

For a time, when he was a student at Oxford’s Worcester College in the early 1950s, Rupert Murdoch kept a bust of Lenin on his mantel. His politics were more liberal then—as a young man he was a vocal supporter of the Labour Party in both Britain and at home in Australia—but he was never a Communist. Vladimir Ilich Ulyanov’s function was mostly to piss people off.

Provocation is the overarching theme in Murdoch’s life. He relishes outrage—how it keeps his opponents and subordinates off balance. How his reputation for disagreeable opinions somehow frees him from social constraints like small talk or basic politeness. And he loves the fact that making people angry makes him money.

Born in 1931 to Melbourne aristocracy—his father, Sir Keith, ran a chain of regional newspapers, and spotted the debutante picture of his future wife Elisabeth in his own pages—rebellion was an early talent. Rupert “was not the sort of person who liked playing in a team,” his mother, still going strong at 102, once told an interviewer. At Geelong Grammar, the elite Aussie private school that Prince Charles would attend decades later, Murdoch clashed with teachers and classmates. Oxford was hardly a better fit for a brash young colonial. And when his father died suddenly in 1952, the 22-year-old left school gratefully, taking a job on Fleet Street, working for another press baron, Lord Beaverbrook, a.k.a. Max Aitken of Newcastle, N.B., at the Daily Express. The internship lasted only a few months, but the do-anything-for-the-story lessons he absorbed shaped his career and life.

Returning home, Murdoch took over the reins of the 75,000-circulation Adelaide News, learning every aspect of the newspaper business from the executive suite. Within a few years, he added the Sunday Times in Perth and a weekly women’s magazine to the family stable. In 1956, he married wife number one, Patricia, an airline stewardess and part-time model. (Their only child, Prudence, was born two years later, and the marriage ended in divorce in 1967.) In 1964, Murdoch launched the Australian, a national broadsheet that earned a reputation for quality, but only turned its first profit 21 years later.

But it is the News of the World that made him what he is today. In 1968, Murdoch rode to the “rescue” of the Carrs, the paper’s founding family, helping beat back a takeover bid by Robert Maxwell. (The family’s decision to back the Australian interloper over the Czech-born, Jewish one quickly came back to haunt them when Murdoch forced them out in a matter of months.) A year later, he bested Maxwell again in a contest for another London tabloid, the Sun. Turning the editorial focus to crime, scandal and sex—topless page three girls were an early Murdoch innovation—he soon had both papers turning enormous profits. The mass popularity of his products, however, bought him little respect among Britain’s movers and shakers. Private Eye, the satirical weekly, dubbed him the Dirty Digger (a First World War-vintage anti-Aussie slur). In London, he and his second wife, Anna—more than a decade younger—were treated like social pariahs.

But for Murdoch, the benefits of being highly successful outweighed the costs of being deeply unloved. In the early 1970s, when he turned his sights to America, he brought the same crass tabloid formula to the New York Post. By 1977, when he wrested away control of New York magazine from its revered founder Clay Felker, he was already infamous enough to merit a Time “Extra!!! Aussie Press Lord Terrifies Gotham” cover that pictured him as King Kong astride the Twin Towers. “He began as an insider; became an outsider because people didn’t understand he was an insider; became such a successful outsider that he becomes, once again, necessarily an insider,” Wolff summarizes in his biography. “But by that point, having only contempt for insiders, he has to find ways to be an outsider again. Offending polite sensibilities becomes his hobby and calling card.”

With a personal net worth of US$7.6 billion, Rupert Murdoch ranks just 122nd on Forbes magazine’s 2010 list of the world’s filthy rich. He punches well above his weight on their tally of the world’s most powerful people, however, coming in at number 13. (Among business moguls, only Bill Gates, at number 10, is judged to have more global influence.) In part that has to do with News Corp.’s almost unrivalled reach—newspapers on three continents, a movie studio, international satellite services, the most popular news channel in the U.S., and a TV network that boasts both the Super Bowl and The Simpsons. But it is also about Murdoch’s willingness to use his properties to advance his own agenda.

In the U.K., for example, the endorsement of the Sun—and presumably the votes of its millions of blue-collar readers—has been considered a crucial stepping stone to electoral victory since the Thatcher era. In 1992, when John Major’s Conservatives pulled out a surprise win over Labour’s Neil Kinnock (whom the paper vilified with gusto), the morning-after headline was, “It’s the Sun Wot Won It!” In his memoirs, former prime minister Tony Blair writes of his decision to go to Australia in 1995 and court Murdoch, jokingly comparing it to Faust’s efforts to “cut a really great deal with this bloke called Satan.” Labour faithful were outraged, recounts Blair, but he had little choice if he wanted to win. “Now it seems obvious: the country’s most powerful newspaper proprietor, whose publications have hitherto been rancourous in their opposition to the Labour Party, invites us into the lion’s den. You go, don’t you?”

Murdoch’s support came with a price, however. His staunch anti-European Union views directly influenced Blair’s decision to not push ahead with a referendum on joining the euro in 2001. So, too, the media mogul’s vociferous support for George W. Bush’s plans to invade Iraq in 2003. “Whenever any really big decisions had to be taken, I had the impression that Murdoch was always looking over Blair’s shoulder,” Lance Price, Downing Street’s former director of communications, wrote in his book, The Spin Doctor’s Diary.

Perhaps it’s that direct access to the levers of power that explains Murdoch’s continued infatuation with his papers, which are responsible for a small, and ever-shrinking, share of News Corp.’s almost $33 billion in annual revenue. (The Post, for example, is said to lose almost $50 million a year; in comparison, Fox News turned a $700-million profit in 2010.) His editors are used to receiving packets of clippings from him covered in scribbled red-ink notes, and he is in regular phone contact. At other times, the peripatetic octogenarian just shows up unannounced in his various newsrooms. “I never got an instruction to take a particular line, I never got an instruction to put something on the front page?.?.?.?but I was never left in any doubt what he wanted,” Andrew Neil, who was editor of the Sunday Times for 11 years, told a British House of Lords committee in 2008. “In every discussion you had with him, he let you know his views. On every major issue of the time, and every major political personality or business personality, I knew what he thought. And you knew, as an editor, that you did not have a freehold, you had a leasehold.”

Murdoch isn’t big on apologies—or backing down. During the Falklands War, when a British submarine sank the Argentinian cruiser General Belgrano, killing 323—about half that country’s casualties in the conflict— the Sun’s front page headline was “Gotcha.” When editors began to rethink their triumphalism a few hours later, and softened the line to “Did 1,200 Argies Drown?” for subsequent editions, the owner was the only one to object. In 1983, his quality broadsheets the Times and the Sunday Times got caught out by a German forger peddling diaries that purportedly belonged to Adolf Hitler. Two historians who flew to Germany to examine the volumes initially declared them to be genuine. But as the Sunday Times prepared to publish the first extract, doubts had started to arise. One of the experts, Hugh Trevor-Roper, also known as Lord Dacre, made a panicked phone call to the paper’s editor, who in turn called Murdoch to ask if he should stop the presses. “F–k Dacre. Publish,” was the Australian’s immortal response. Similarly, a 2007 scandal over the Page Six gossip column at the Post, with allegations that its reporters took bribes, waged personal vendettas, and attempted to shake down a billionaire friend of Bill Clinton’s, resulted in the firing of a single junior staffer. In one of the associated lawsuits, Col Allan, the paper’s Aussie editor-in-chief, was accused of accepting free liquor and sexual favours at a local strip club. Two years later, several former female Post staffers sued him for sexual harassment. He remains on the job.

In fact, there have only been a couple of select occasions in the past decades when News Corp. properties have issued mea culpas. In 1989, after surging crowds crushed 96 people to death during a soccer match between Liverpool and Nottingham at Hillsborough stadium in Sheffield, England, the Sun went to press with an unsourced story alleging that Liverpool fans “picked the pockets” of the dead and dying, and urinated on rescue workers. Four years later, after much outrage, Kelvin MacKenzie, the editor responsible, told a House of Commons committee that it was “a terrible mistake.” Later, he took it back, saying he only apologized because Rupert Murdoch ordered him to. The more infamous climbdown came in 2006, when News Corp. abruptly cancelled plans to publish a book by O.J. Simpson called If I Did It, and aired a four-hour interview on Fox outlining his “theoretical” confession to the murder of his wife and her friend. Judith Regan, the Murdoch protege who developed the project, subsequently lost her job, and filed a $100-million lawsuit. It was settled out of court for somewhere between $10 million and $30 million.

So, Murdoch’s public displays of regret and contrition over the current scandal might be seen as an indication of just how serious the trouble really is. “Recent allegations of phone hacking and making payments to police with respect to the News of the World are deplorable and unacceptable,” the CEO said in a statement this week. “We are committed to addressing these issues fully and have taken a number of important steps to prevent them from happening again.” The paper has been sacrificed, and the company is “fully and proactively” co-operating with the various police investigations. Although one wonders how much more remains to be disclosed: “The worst is yet to come,” Rebekah Brooks, the chief executive of the British papers, reportedly warned staffers. She has offered to resign, but Murdoch refused to let her go (David Cameron, her friend, has said that he would have accepted the offer). Brooks, Rupert and James Murdoch have all been “invited” to appear before a Commons select committee on culture to explain themselves. And the coalition government has indicated that it will support an opposition motion calling on News Corp. to withdraw its bid for BSkyB. The company, contending with its slide on the markets, has announced plans to buy back up to $5 billion of its own stock over the next year. And the latest rumours suggest Murdoch might even be looking for a quick exit from the British scene, seeking a buyer for all his papers.

What’s getting lost in the feeding frenzy is that the renewed police investigations and political probes are unlikely to stop with just one chain and owner. When the scandal first broke in 2006, after it was revealed that a private investigator had hacked phones belonging to princes William and Harry on behalf of News of the World, a report by Britain’s information commissioner revealed such privacy invasions to be a common practice amongst the British press. Evidence gathered by police showed that 305 journalists from 31 different publications had made hacking requests to just that single PI. News of the World was fifth on the list, behind Associated Newspapers’ Daily Mail and Mail on Sunday, and Trinity Mirror’s Sunday People and Daily Mirror. Even the left-wing Guardian’s Sunday edition, the Observer, was implicated, with four journalists having made 103 separate requests.

But Murdoch, Australian by birth, an American citizen since 1985, may be the easiest target. Already a villain in the public imagination—not just for his politics, but as a purveyor of tawdry American Idol-style U.S. culture—he will not be greatly missed. And the questions about his judgment that have steadily grown since his 1998 late-life crisis, when he ditched wife number two, Anna, after 31 years of marriage to hook up with Wendi Deng, a woman 38 years his junior, are only getting louder. In the course of a few short years, family succession plans have abruptly shifted from Lachlan, his oldest boy with Anna, to their daughter Elisabeth, and now to their son James. If circumstances force him to change his mind again, there are few options: his and Wendi’s daughters Grace and Chloe are just nine and eight. At 80, it seems unlikely Murdoch can hold on until they come of age.

The power of the press belongs to those who own one, goes the old saw. For a long time, Rupert Murdoch has certainly behaved that way. Now, it seems the balance has shifted.