Redeeming the Pashtun, the ultimate warriors

Lasting peace in Afghanistan won’t just need talks with the Taliban. It will also require rescuing a shattered Pashtun culture

FILE – In this Aug. 5, 2012 file photo, Pakistani Taliban patrol in their stronghold of Shawal in the Pakistani tribal region of South Waziristan. Pakistan has stepped up outreach to some of its biggest enemies in Afghanistan, a significant policy shift that could prove crucial to U.S.-backed efforts to strike a peace deal in the war-torn country.The target of the diplomatic push has mainly been non-Pashtun political leaders who have been at odds with Pakistan for years because of the country’s historical support for the Afghan Taliban, a Pashtun movement. (Ishtiaq Mahsud/AP)

Share

The severity in the eyes of the Taliban commander hammered home his point: “Kandaharis are the fiercest fighters in Afghanistan,” he said. It was February 2006, just as Canadian soldiers were arriving in Afghanistan’s southernmost province. “Fighting is in our blood,” he told Maclean’s. The twentysomething fighter was a hulking mass of a man who, by his own reckoning, had participated in jihad for more than a decade of his short life. He was a Pashtun who seemed to embrace a culture of violence and revenge, and exhibited a fearlessness that bordered on the insane.

After nearly four decades of war, the Pashtun people in both Afghanistan and Pakistan have developed a reputation for violence. It’s an image—partly based on fact, but mostly fictitious—that comes up any time there is talk of a peace deal with the Taliban. Detractors, largely from Persian-speaking ethnic groups from Afghanistan’s north, inevitably fall back on the warrior argument: The Taliban, a political group mainly made up of the Pashtuns, will never surrender, nor will they negotiate, they say. Their culture leaves no room for peace because they, as a people, have never known peace.

The myth persists, even at a time when negotiating with the Taliban seems more of an inevitability than it ever has before. Most Afghan experts now agree that the Taliban will play a political role in a future Afghanistan. Last month, Afghan President Ashraf Ghani, a Pashtun himself and an anthropologist with a more subtle understanding of Pashtun history and culture than most, called on the more intransigent members of Afghanistan’s power brokers (mainly former Northern Alliance commanders) to accept a peace process with the Taliban. “Anyone who has a political reason for being against our government must enter the political process,” he said during a speech on April 30. “This is not preferred, but rather, is compulsory.”

The Pakistanis, for the first time in more than three decades, seem to be on the same page. On the same day as Ghani’s speech, Pakistan’s foreign ministry spokesperson condemned the Taliban for pursuing their perennial spring offensive. “We have already condemned the spike in violence, and we would like to see a national reconciliation process in Afghanistan,” Tasneem Aslam said in her weekly press conference.

The overtures, while heartening, are only a first step on a very long and difficult road. Negotiating a political peace is one thing; rehabilitating Afghanistan’s shattered Pashtuns is quite another. The damage caused by four decades of conflict, mostly affecting the Pashtun belt in Afghanistan and Pakistan, has transformed an entire culture. The detritus from those tragic years has obscured the fact that the Pashtuns and, by extension, the Taliban, have historically embraced negotiations and compromise. Their culture was once celebrated for its poets, storytellers and musicians, but has now become best known for its warriors and religious fanatics. So how did the Pashtuns reach such a nadir—and can the process be reversed?

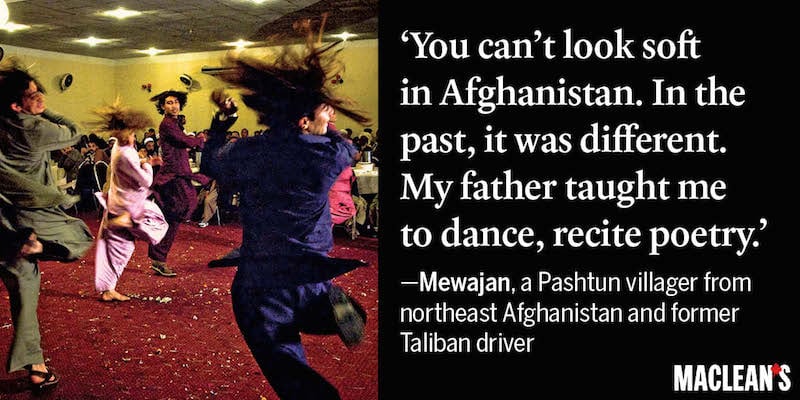

A few months after the run-in with the Taliban commander in Kandahar, on a windswept mountaintop in a remote part of northeastern Afghanistan, a different side of the Pashtuns was on display. A man named Mewajan, after weeks of boasting, finally broke out his dance moves. To the beats of Nazia Iqbal, Pashtun music’s most beloved popular singer, Mewajan unfurled his arms like a bird, raised his densely bearded face to the sun, and began tracing out circular patterns on the rock-strewn earth, twirling his hands and bobbing gently to the beats of the traditional dhol drum.

It was a surreal sight, considering Mewajan’s history: A hard-edged Pashtun villager from the northeast, he embodied all the characteristics for which the Pashtuns have become infamous. Mewajan had once been a driver for the Taliban regime in Afghanistan, working with senior commanders during their short-lived government in the late 1990s. Since 2002, he’d used his vast network of contacts to help Maclean’s access those same commanders. Over the years to come, he would provide access to some of the most dedicated fighters in Afghanistan’s south, including the ones in Kandahar.

He had worked hard on his image; after so much war and instability, it paid to be tough in Afghanistan. But when the facade fell, what was left was an intellectual and artistic depth most Westerners rarely see among the Pashtuns. Mewajan was also a music aficionado (despite living through a Taliban ban on music); he could recite classical Pashtun poetry and ancient parables by heart, and would spend hours a week tending to the rose garden he’d planted in the courtyard of his mud-brick house. “You can’t really look soft in Afghanistan these days,” he said. “In the past, it was different. My father taught me to dance, recite poetry and appreciate music; my mother taught me the old Pashtun stories. When they were young, before the Soviets invaded, life was different. Then everything changed.”

During the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan in the 1980s, military dictator Zia ul Haq, with the help of Saudi Arabia’s Wahhabis and funding from the U.S., had embarked on a Machiavellian program to create an army of holy warriors that would cause havoc for the Red Army in Afghanistan. The guinea pigs for this cynical social experiment were the Pashtuns. Religious seminaries in the Pakistani Tribal Areas became the centre of jihad ideology, incorporating elements of Wahhabi religious doctrine into the predominantly Deobandi Islam practised by the Pashtuns.

Pashtun religious culture has never recovered. Madrasas in Pakistan’s northwest continue to churn out young jihadists with a single-minded mission of toppling what they perceive as puppet governments in Afghanistan and Pakistan. The shrines of Sufi saints—poets and philosophers venerated by Pashtuns—now sit empty and dilapidated in Pakistan’s Tribal Areas.

The mullahs who rose to power in northwest Pakistan in the wake of the political chaos of the U.S.-led invasion of Afghanistan were the products of Zia’s social engineering. They wasted little time in using their newfound political influence to impose their moral code on society. In one of their first acts, they banned music from public transport vehicles; then movie cinemas were ordered to take down posters depicting the heroes and scantily clad heroines of the Pashtun film industry. Not long after, the Taliban threats began: Owners of CD shops were ordered to shutter their doors or face the consequences; singers were abducted and killed.

“They came to my shop. They burned everything,” says Muhammad Waseem, a 52-year-old master tabla-maker. His family had operated its musical instrument shop in Dabgari bazaar, the music district in Peshawar’s riotous old city, for decades. After the 2004 attack, he managed to re-establish a more modest version of his workshop in another district of the old city. He was a lucky one. Many musicians who made a decent living playing at wedding parties and festivals have now resorted to working as day labourers.

The Taliban’s crusade against music strikes many Pashtuns as ironic. “Let me tell you: The Taliban themselves listen to music,” says Nasrullah Jan Wazir, director of the Pashto Academy at Peshawar University. “Many of them will have recordings stashed away at home that they will listen to in private. Music is an integral part of Pashtun culture.”

“These bans make no sense in the context of Pashtun tradition,” says a senior member of the Abasin Arts Council in Peshawar, requesting anonymity because he fears a Taliban backlash. “Even poetry has been deemed un-Islamic by the Taliban, but Pashtuns have been composing poetry for hundreds of years, poetry that celebrates Islam and the Prophet Muhammad. How can this be un-Islamic?”

Rolling back the damage inflicted on Pashtun culture is more urgent now than ever before, says Abaseen Yousafzai, a professor of Pashto language and literature at Islamia College in Peshawar. Both Afghanistan and Pakistan “have realized that bringing peace means creating a cultural space in which Pashtuns can rediscover their roots,” he says. “We are a peaceful people, but people around the world are wondering what is wrong with us.”

There is some hope: The mullah-led government in Pakistan’s northwest fractured in 2005 and ultimately collapsed in 2008. The damage it perpetrated remains deeply embedded in the Pashtun psyche, but the atmosphere is changing. Pashtun intellectuals are banding together, uniting around institutions such as the Pashto Academy in a concerted push to revive Pashtun intellectualism.

“Our mission is to rebuild a Pashtun intellectual class,” says Moazzam Jan Moazzam, chief executive of the World Pashto Congress in Peshawar. “Malala Yousafzai [the teenage Pakistani education activist who was nearly killed by the Taliban] is a Pashtun who lifted her pen against guns. I think this gun culture is on its way out. I promise you: In two years, you will see, this will not be Mullah Omar’s Pakistan. This will be Malala Yousafzai’s Pakistan.”

But, for the Taliban leaders and their supporters, the culture wars remain a powerful political tool to mobilize the masses against the spectre of foreign interference. For them, even a figure like Malala represents a threat: The Nobel prize laureate’s attempts to re-define Pashtun-ness challenges the warrior narrative. And the attempt on her life was a clear indication of how far they are willing to go to protect it.

Mewajan felt it on that remote mountaintop on a warm spring day back in 2006. His dance performance, lively and liberating, was short-lived. It wasn’t long before he noticed the dust cloud kicked up by a 4×4 edging closer to our location. The change that came over him was instantaneous. Mewajan’s demeanour hardened; he transformed again into the hard-edged Pashtun villager from the northeast. He became what was expected of him: a former Taliban driver, and a man who knows exactly what it means to be a Pashtun.