The U.K’s ‘mummy wars’ heat up

Stay-at-home-moms react to a new tax scheme they say is unfair

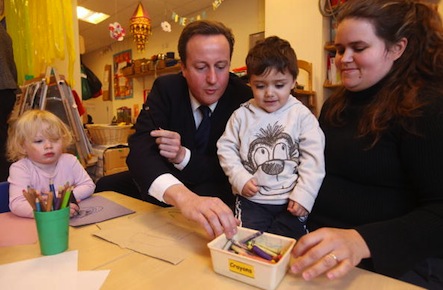

Oli Scarff/Getty Images

Share

Nick Clegg, the U.K.’s deputy prime minister, found himself under fire this week in Britain’s version of the so-called mummy wars.

During the Liberal Democrat leader’s regular radio phone-in show, he was attacked by a stay-at-home mother, who expressed her outrage over the government’s new child care tax-voucher scheme, which provides benefits only to families in which both parents work.

“You probably think what I do is a worthless job,” said Laura from south London, a self-described homemaker who declined to give her full name. She then went on to lambaste Clegg’s government for providing “absolutely no provision in the tax system for families like myself.” Her voice is just one in a growing chorus of increasingly desperate housewives who feel the U.K. government’s new child care scheme is unfair to those families in which one parent stays home while the other goes out to work.

It’s an awkward situation for the Tory-led government, since so-called “traditional” families, in which the father is the breadwinner and the mother tends the home fires, have historically formed the backbone of middle-class Tory voter base.

The voucher, which rewards either single parents or co-parents who earn up to $232,400 each, but not those earning under the income tax threshold of $15,500, has also come under heavy criticism for excluding the working poor (who do receive child care benefits, but on a separate scheme).

Controversial as they are, the measures are a response to one of the country’s big problems. They’re meant to help offset the soaring cost of child care in Britain, which, according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, amounts to a staggering 43 per cent of average family incomes. Compare that to neighbouring France, Denmark or Germany, where child care costs amount to less than 15 per cent of average household budgets.

According to a recent survey by the U.K.’s Daycare Trust, a spot in a nursery now costs 77 per cent more in England than it did in 2003, while average earnings have remained roughly the same.

The government believes, quite rightly, that the cost of child care has become the single biggest quality-of-life issue for working families today. A document accidentally leaked by the Treasury earlier this month explained that the government is trying focus its resources on parents who are determined to work. “Working families who are struggling with their child care costs, or families where parents want to go to work but can’t afford to, are in greater need of state support for child care than families where one parent chooses to stay home and look after their children full-time.” Or as a spokesperson for the prime minister more bluntly put it, the government is “supporting those who want to work hard and to get on.”

Not surprisingly, the covert message here—that parents who choose to care for their children full-time are choosing not to “work hard”—has gone down, as the odd British saying goes, like a cup of cold sick. The Telegraph accused Cameron of making a “slur upon stay-at-home mothers,” and the Daily Mail declared the beginning of a “backlash from stay-at-home mums.” But not all commentators agree that homemakers deserve public respect or, indeed, tax benefits. In a controversial article, “The mother myth,” published earlier this year in The Spectator, Carol Sarler declared what the Cameron government seems to be passively inferring: that middle-class stay-home mums are, for the most part, privileged and lazy. “There never was such a thing as a full-time mother,” Sarler writes. “She is a recently constructed, absurdly quixotic myth. The full-time mother has never existed for the simple reason that, exempting only the fleeting years of infancy, mothering is not, and has never been, a full-time job.”

Needless to say, this was not the message Clegg conveyed to Laura from south London while defending his government’s new child care scheme. Instead, the deputy PM was agonizingly vague, saying that while he “massively admired” Laura’s choice to look after her own children, the new measures were “all about what we can do in government to give people the greatest choice that they want and need in their own lives.”

Except, as many commentators have pointed out, the government’s earlier decision to cut the U.K.’s child benefit for higher earners (as of this year, only households in which both parents earn less than $93,000 a year and under six figures in total qualify for the $2,000 per-child, per-year benefit) can be seen as a negation of personal choice. In essence, the government is saying to middle-class parents: if you want our support, get a job.

It’s a difficult message to deliver to families in the middle of a triple-dip recession, especially when the new tax provisions don’t even go into effect until 2015 (which, incidentally, just happens to be the next election year). In the meantime, hundreds of thousands of British families will make do without any tax provisions at all. As child care costs continue to rise and incomes continue to flatline, the British middle classes are feeling the pinch—no matter what side of the mummy wars they fall on.