Time for ‘tu’ to go?

Some French speakers are bewildered by the loosening of long-held rules of grammatical etiquette

Share

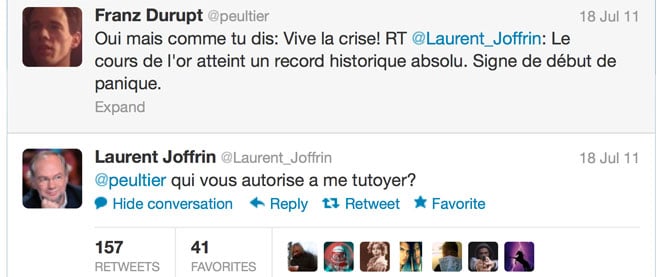

In July 2011, Franz Durupt, a young journalist for Le Monde’s website, committed an error of grave proportions. On Twitter—in an otherwise unremarkable comment about the eurozone crisis—he referred to Laurent Joffrin, a Parisian editor, using the informal second-person “tu” instead of the formal “vous.” Joffrin did not let the lexical affront slide. He tweeted a 31-character battle cry: “Qui vous autorise a me tutoyer?” (“Who said it was okay for you to ‘tu’ me?”)

The now notorious exchange was reprinted endlessly in French broadsheets. Joffrin came to epitomize France’s semantic old guard. But, as wise folks might one day say, real life is more complicated than a Twitter stream. In recent decades, France’s grammatical structures have loosened, leaving some French speakers bewildered, says Australian French professor Bert Peeters, co-editor of the book Tu ou Vous: l’embarras du choix. What used to be a simple snap judgment—formal or informal?—has become “an uneasy choice.”

The seeds of this malaise were planted in 1789, when Parisians stormed the Bastille and France was awash in revolution. As the French masses rose up against a long-entrenched aristocracy, “vous”—the syntactic equivalent of doffing one’s cap—was demonized. “Revolutionaries wanted to do away with all that aristocratic business,” says Peeters. “They wanted everyone to be on a ‘tu’ basis. But that didn’t last long.” Enter Napoleon Bonaparte, the emperor famed for restoring the ancient regime; re-enter the formal vous.

There was tumult again in 1968, when student demonstrators took to Paris’s streets. Protesters “argued that class difference should be done away with, not built into the language. Vous received quite a battering,” says Peeters. On Twitter, that most egalitarian of salons, tu now reigns.

Offline, the terrain is muddier. Eva Havu, a Romance languages lecturer at the University of Helsinki, studies French pronoun usage. She says that while soixante-huitards (1968 revolutionaries) remain dogmatic about tu, more ideologically lax youngsters have backtracked, embracing vous, along with the formality and emotional detachment it implies. But only sometimes.

Often, French adolescents don’t know quite what to do. Recently, Havu interviewed children about their pronoun use. “Young boys said that when they wanted to invite a girl to the cinema, they didn’t know how to address her: tu or vous? It was very sweet.”

“Things can get complicated,” agrees Mathias Lebargy, a soft-spoken English teacher in Normandy, “with colleagues who are about the same age as me—no one is higher up on the hierarchical ladder [and thus able] to give the other permission to switch to tu.”

Lebargy plays it prudently; he is generous with vous “even if that means, from time to time, coming across as a bit uptight.” This did not serve him well among Canada’s notoriously tu-happy Quebecers. On a recent trip to Montreal with his Canadian girlfriend, Lebargy recounts, “We were window shopping and the seller started asking me questions about Normandy using tu—quite shocking for a Frenchman!”

The effects of linguistic anarchy are also felt in the policy realm. In 2007, after Nicolas Sarkozy’s election, the slick new president ruffled feathers by launching a barrage of tus at fellow politicians. Much was made of Sarkozy’s decision to use tu with German Chancellor Angela Merkel and Russian President Vladimir Putin—and their decisions not to return an informal greeting. Gone was the genteel former president, Jacques Chirac, who famously used vous with his wife.

There have been recent efforts to rein in the unruliness. In May 2007, the government ordered the use of vous in schools. “It is indispensable that children vouvoient their teachers,” Xavier Darcos, then the education minister, explained, “so that everyone is in their right place.” French police were recently banned from using tu during identity checks. On the other hand, many businesses have loosened up, instructing employees to ditch their starched collars and fussy pronouns.

Across Europe, similar befuddlement reveals itself. Spaniards wrestle with tu and usted. In Italy, the formal lei is on its way out. In Finland, the formal second person has made a slight comeback. In Germany, the choice between du and Sie is sometimes a matter of history. Under Communism, East Germans were pressured to use the fraternal du; in reaction, some now opt for Sie. In Austria, altitude is also a factor. Rafael Milan, a well-heeled Viennese Ph.D. student, says in the Alps, “the higher you climb, the more informal [language] becomes.” In general, it “comes down to social and cultural finesse.”

On ground level in Paris, that 2011 Twitter exchange is now a symbol of generational clash. For some, it is also the consequence of an ideological void. Without the egalitarian dogmatism of the soixante-huitards, or the regimented etiquette of their forebears, French youth are semantically adrift, often to awkward effect. For his part, Durupt never meant to be a muckraker when he tweeted his “tu”: “The main reason I used tu was that I had reached Twitter’s limit of 140 characters.”