Calgary’s ‘May As Well’ Olympic bid—modest ambition that still costs billions

Jason Markusoff: The value proposition being sold here is not an Olympics that builds new things. So what exactly does Calgary expect to get?

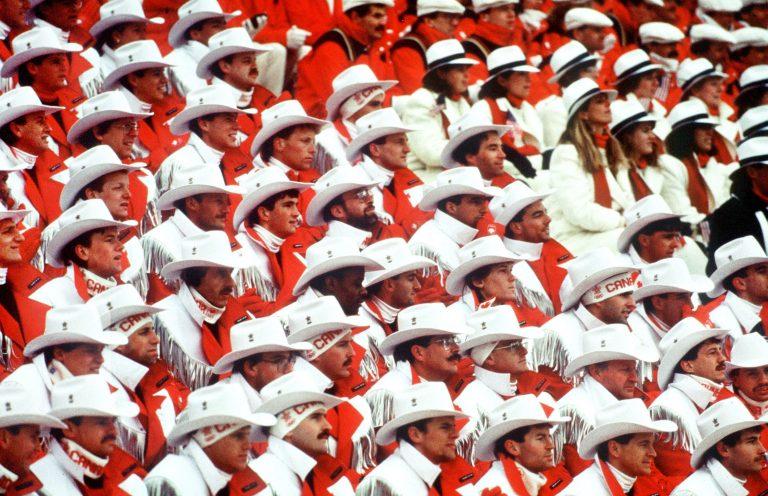

Canada’s olympic athletes participating in the opening ceremonies at the 1988 Winter Olympics in Calgary. (CP PHOTO/COC/ Ted Grant)

Les athletes olympique lors des cérémonies d’ouverture des Jeux olympiques d’ hiver de Calgary de 1988. (PC Photo/AOC/Ted Grant)

Share

In November, Calgarians will vote on whether they want to hold the Winter Olympics, like the city did in 1988. The population was 657,000 at the time; since then, it’s unbelievably doubled.

The boosters pushing Calgary towards a “yes” on the plebiscite insist they aren’t merely trying to relive past glories. Yet much of the construction supposed to stimulate the post-oil-crash civic economy would serve to refurbish past glories: the Saddledome, the speed-skating oval, the Canada Olympic Park bobsled and ski/snowboard venue, and faded downhill resort Nakiska—the grand legacy pieces from the 1988 Games. (Many of those buildings, including the Saddledome and football’s McMahon Stadium, have been tabbed for replacement for several years; the hockey arena is now the National Hockey League’s oldest, and the Calgary Flames organization has eternally been pushing for something (newer, shinier and heavily subsidized).

The value proposition being sold here is not an Olympics that builds new things, at least not in the tangible sense. There’s no new convention centre being envisioned, no twinned highways to the mountains, no transit upgrades like a rail link to the airport, all of which formed part of Vancouver’s $7-billion Winter Olympics in 2010. In fact, part of Calgary’s recycling mindset includes using Whistler’s ski jump instead of finding a suitable replacement in Alberta. Calgary’s bid corporation may also farm out curling events to Edmonton’s new arena. By outsourcing some events and largely making do with existing infrastructure, Calgary is proposing an Olympics that cost a mere—only!—$5.2 billion.

It’s the sort of bid the International Olympic Committee (IOC) would have found laughably shabby in past years. But after the colossally expensive 2008 Beijing (US$44 billion) and 2014 Sochi Olympics ($51 billion) and the white elephants left in their wake, the sports bureaucrats found almost nobody wanting to bid for the 2022 Winter Games, awarding them to Beijing, a city not known for its snow. (It was that, or give it to Almaty, Kazakhstan.) So the IOC has begun preaching relative frugality. Beijing will reuse its Summer Olympics’ aquatic centre for Winter Games curling. In Paris, the 2024 Summer Olympics will feature a temporary beach volleyball course on the Champ de Mars by the Eiffel Tower. Calgary’s would-be chief rival for 2026 may be a three-city Italian bid including Turin, the 2006 host; an early favourite for the following winter quadrennial is Salt Lake City, the Utah city with its 2002 Olympic venues ready for another go-round.

READ MORE: Putting the ‘limp’ in Olympics: Calgary’s 2026 bid lives on, but for what, exactly?

The fact the IOC won’t mind an Olympic bid bound together with duct tape and new paint layers doesn’t mean that Calgarians will accept it. In lieu of new infrastructure to woo supporters with, the “yes” campaign and bid corporation must sell residents on various different notions. One argument is that Calgary eventually has to rehabilitate its amateur sports venues and build the sort of affordable housing left behind by an athlete’s village, and this way can leverage federal and provincial subsidy instead of paying solely through civic tax dollars—making this a We May As Well Games.

There are the usual economic benefits pitches with the usual dubious projections. We’re told the Olympics could spur reconciliation with Indigenous communities, and hosting the Paralympics will make Calgary more accessible, both things any decent city should be doing anyway but a kick in the pants wouldn’t hurt.

Then there’s the more ethereal idea that Calgary gets to strengthen the community and “tell the story.” This happened already in 1988. “Calgary was suddenly moving out of its role as a regional hinterland,” sociology professor Harry Hiller reflected on the 25th anniversary. “It would no longer be a Cowtown, an agricultural base. It would undergo a major transformation.” Three decades after Calgary was thrust onto the world stage, does it now want to become world stagier?

READ MORE: Calgary’s bad 2026 bid: $4.6 billion for the discount Olympics

The afterglow of 1988 shone bright in Calgary; obnoxiously so, to many. An old Alberta joke went: how many Calgarians does it take to change a lightbulb? Three. One to replace the lightbulb, two to reminisce about how great the ’88 Olympics were. It’s tempting to think that a world-level project could help rescue Calgary from its current doldrums, both economically and spiritually. But it’s folly to guess at where 2026 will land in the city’s perennial boom-bust cycle, let alone to think today’s prolonged funk will persist then.

The major study commissioned to measure the impact of Vancouver 2010 found that the tourism and reputational uplift were minimal, though it gave some credence to “the red mitten effect”—the national pride that was raised alongside amateur athletics funding.

The big lasting impacts, the Canadian Olympic Committee’s study found, were the new train line, wider Whistler highway and Vancouver convention centre. Calgary’s Olympic bidders have decidedly avoided those sort of benefits. Perhaps they were worried that provincial and federal financial support may not stretch beyond the billions the governments are already expected of provide. Calgarians now get to decide if it’s worth it to get the warm fuzzies from the mittens without a whole lot else to show for it.