America withdraws from Afghanistan, and fails one more time

Adnan R. Khan: The list of America’s unfinished business is long, and bloody. And it is growing longer with the plan to abandon Afghanistan in its time of need.

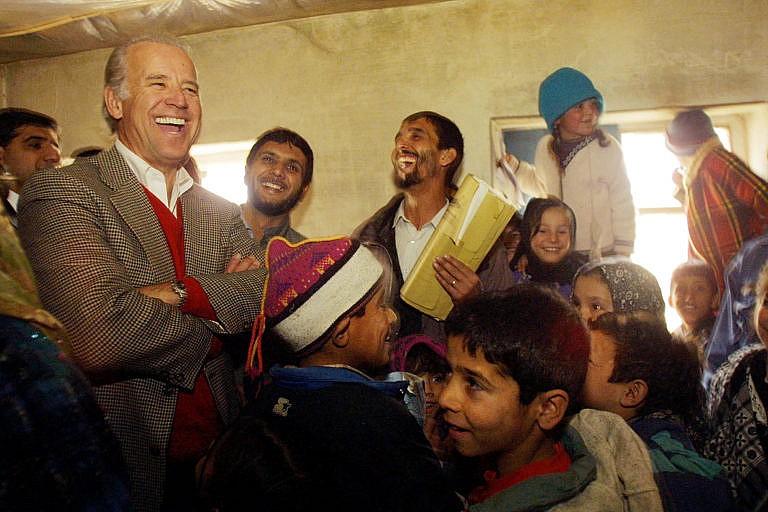

Biden visits Kabul, Afghanistan, in 2002, when he was chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee (Paula Bronstein/ Getty Images)

Share

For anyone’s who has followed the war in Afghanistan closely over the past two decades, listening to Joe Biden’s speech last week about the U.S. withdrawal was an exercise in anger management. It was refreshing, of course, to hear a U.S. president at least try to make a sound argument after four years of incoherent nonsense. Biden, or his speech writers at least, made an earnest attempt to detail the reasons why it is no longer in the U.S. interest to remain in Afghanistan. Their argument sounded plausible on the surface. In a nutshell, Biden based his decision to withdraw on three factors:

- The goals of the 2001 invasion were to bring Osama bin Laden to justice and destroy al Qaeda’s ability to operate in Afghanistan. The U.S. accomplished those goals when they killed bin Laden in 2011.

- The U.S. is spending billions of dollars a year and using thousands of troops to prop up a government in a place that is fundamentally ungovernable.

- There are more pressing threats to deal with in the world, including the rise of China and the resurgence of Russia, the rise of authoritarian regimes, and the fracturing of the post-WWII global order.

The argument, however, is fundamentally flawed in every instance.

Firstly, if the original goal in Afghanistan had been solely focused al Qaeda and bin Laden, the U.S. would have accepted the Taliban’s surrender on Dec. 7, 2001. Instead, Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld rejected that offer outright, opting instead for total military victory. In doing so, the U.S. committed to something other than ensuring al Qaeda would no longer enjoy a safe haven in Afghanistan; it committed to helping Afghanistan ensure the Taliban would never again take control of Afghanistan.

But it never took that commitment seriously. If it had, it would have invited the Taliban to participate in the Bonn agreement and force it to join a broader unity government. It would not have installed a heavily-centralized government in Kabul drawn from former warlords who had lost the people’s trust during the devastating civil war of the 1990s. It wouldn’t then have turned its back on Afghanistan and started a new war in Iraq.

By the time Barack Obama took over the White House in 2008 and realized there was still a war going on in Afghanistan—and his side was losing—the damage had been done. The warlords, more interested in buying up villas in London and Dubai, had siphoned off billions of dollars in aid intended to rebuild Afghanistan. Bickering over aid industry spoils had sown corruption, apathy and distrust among the Afghan people. When Canadian forces were deployed to Kandahar in 2006, those were the major challenges they faced.

But indeed, the U.S. did finally succeed in killing bin Laden and if Biden had had his way then, the American involvement in Afghanistan would have come to an end. “That was 10 years ago,” Biden said during his speech. “Think about that. We delivered justice to bin Laden a decade ago, and we’ve stayed in Afghanistan for a decade since.”

But it’s hard to tease out what Biden’s logic is exactly. Bin Laden was killed in a compound in Abbottabad, Pakistan, less than 2 km from the Pakistani equivalent of West Point. The Pakistani military denied it had any knowledge bin Laden was there, which is of course ridiculous.

The killing of bin Laden was not a ‘mission accomplished’ moment. It was a moment of sombre reflection; it was a reminder that there would be no peace in Afghanistan until Pakistani meddling in the country was addressed. It also brought home just how implicated the Pakistanis had become in the intersection between the Taliban and al Qaeda. Indeed, by the time bin Laden was killed, the Taliban were coming increasingly under the influence of the Haqqani network, which has close ties to both the Pakistani intelligence services, the ISI and al Qaeda. The Haqqanis are now arguably the most powerful force inside the Taliban, so much so that one of their members, Anas Haqqani, is a key figure on the Taliban’s negotiating team.

Even in 2011, the writing was on the wall: The first half of the Afghan War had been an abject failure. The second half, after the killing of bin Laden, began with attempts to fix those earlier mistakes, but again, the fundamentals were all wrong. Obama refused the advice of experts who argued that the highly-centralized government in Afghanistan was not working. Instead of tackling that governance issue, he ramped up military operations, raising troop levels to more than 100,000.

The surge, though destined to fall short of defeating the Taliban, wasn’t entirely a failure either. The war is now a stalemate. The Taliban are in firm control of the remotest countryside but the Afghan government, with the help of U.S. and NATO forces, controls the urban and semi-urban centres. More importantly, government-controlled areas account for over 14 million Afghans while Taliban-control covers around 4.6 million of the population, according to the Long War Journal’s live map of Afghanistan. The remaining 14.2 million or so live in contested areas.

The population distribution offers a number of insights. Firstly, if you compare government and Taliban control in terms of physical space, it’s about equal. The wide gap in population density suggests that the Taliban dominate sparsely populated areas. In my experience in Afghanistan, the reason for this is that the majority of Afghans do not support the group. Where there are enough people, there is resistance to Taliban control.

Secondly, the basis for the Taliban’s religious control rests on a purity of ideology that can only be maintained in remote areas that lack services and where the Taliban themselves are the sole source of information. This became plain when the Taliban agreed to an Eid holiday ceasefire in 2018. The brief peace offered opportunities for Taliban fighters to come into populated areas under government control, many for the first time, and interact with locals. They were surprised to find burkas and mosques and people diligently practicing Islam. Some decided not to go back to fighting. The Taliban leadership was reportedly so worried by the defections that it wouldn’t agree to another ceasefire again for two years. The last one, in May 2020, was much more limited in scope; it did not allow fighters to go to government-held areas.

Those successes undermine Biden’s suggestion that Afghanistan is somehow ungovernable, which is, frankly, a racist and colonialist trope often used by western leaders to gaslight their own failures. Afghanistan’s political history is not much different than the history of other nations—at times governed well, at other times poorly. What occupiers like the U.S.—and the Russians before them—failed to appreciate was that Afghan leaders got themselves into trouble whenever they tried to rule by diktat, without the consent of the population. A too centralized government in Kabul has, historically, led to rebellion in the countryside.

That problem remains, in large part, because the U.S. tried to accomplish its goals in Afghanistan on the cheap, relying on a coterie of warlords to run the country. That’s not what Biden will admit, of course. According to him, the Afghan war has been too costly and “keeping thousands of troops grounded and concentrated in just one country at a cost of billions each year makes little sense to me and to our leaders.” He, like others who support the withdrawal, point to the more than $2 trillion spent in Afghanistan since 2001 to argue that the U.S. simply cannot afford to remain in the country when other, more pressing issues are at hand.

That’s misleading. According to Brown University’s Costs of War project, the war in Afghanistan has cost a total $2.26 trillion. More than half of that, however has gone to things like running the defense department, interest on loans and veterans’ care. The actual yearly cost of the war fighting itself, according to The Balance, which based its figures on Brown University estimates, has averaged around $46.65 billion a year over the two decades of the war (higher during the three years of Obama’s surge, of course).

Let’s put that figure in perspective.

In 2018, the Defense Department projected it would spend $45 billion on the war in Afghanistan. Of that, $13 billion would go to U.S. forces in the country, $5 billion to Afghan forces, $780 million to economic aid and the rest to logistical support.

One assumes financial support for Afghan forces will not end with the U.S. withdrawal, nor will economic aid. The substantial funds going to logistical support includes helping NATO forces with things like air support and transport, much of which could be mitigated with increased spending by allied nations. So a more realistic estimate of what the U.S. will be saving when it leaves Afghanistan is in the $13 billion range.

An analysis in 2016 showed that the Pentagon could save more than $20 billion a year by reducing the number of contractors it uses and shifting the work over to equally-capable government employees. Others have pointed out that the Pentagon continues to waste hundreds of billions of dollars on expensive military equipment that is useless for the wars of the 21st century. The “too costly” argument falls apart in the face of that kind of waste. There is clearly something else going on.

Is it then lives lost? Is the U.S. sacrificing too many of its young men and women in Afghanistan? That depends on how you evaluate the value of a life. Clearly, any death is a tragedy, particularly for the loved ones left behind. In 2019, before a withdrawal agreement was signed with the Taliban, total combat deaths in Afghanistan came to 20, in large part because the Afghan army is doing the bulk of the boots on the ground fighting—and dying—with NATO and the U.S. providing logistics and air support.

By comparison, the war playing out inside the U.S.—the one fuelled by America’s gun epidemic—is killing more people every year by multiple orders of magnitude. That is, by definition, tragic.

Which now leaves us with Biden’s last argument: that there are more pressing issues the U.S. must deal with, and Afghanistan is draining resources that could be better spent elsewhere. But the fact is, Afghanistan is not draining too many resources. The U.S. can easily continue its military support of Afghan forces and meet the challenges ahead, if it finally listens to the experts and brings its military planning into the 21st-century rather than keeping it mired in the Cold War.

And the payoffs for Afghanistan have already been significant. Over the last two decades, it has developed its first generation of educated young people who are taking on the hard task of rebuilding its economy and its institutions. It’s a tough slog; they face an entrenched class of old-school elites—empowered by the U.S.— who are unwilling to give up their privilege, but they are making progress. Afghanistan’s cities are now buzzing with private universities and colleges where more generations of young Afghans, including women, are preparing to lead their country once the elite are dislodged, or die off.

All of that is threatened now. Twenty years is too much, the argument goes, when the fact is that the U.S. has really only spent about a decade earnestly trying to stabilize Afghanistan, and a decade for a country so thoroughly demolished by war is not very long.

Biden points out that the world faces rising authoritarianism but glosses over the fact that the popularity of strongmen is intimately tied to the failures of the war on terror over the past two decades, including Afghanistan. The 2015 refugee crisis for instance, which was mostly driven by the war in Syria, sparked a populist backlash in Europe that propelled authoritarian regimes into power in places like Italy and Greece and Hungary. The U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan, almost all experts agree, will lead to more conflict, which will lead to more refugees, which will cause more instability in places like Turkey, further destabilizing an already fragile Europe.

What Biden seems to have missed, blinded perhaps by the myth of American exceptionalism, is that failed and abandoned U.S. foreign policies is what brought us here in the first place: America abandoned Afghanistan after the fall of the Soviet Union, which led directly to the rise of the Taliban and, ultimately al Qaeda; America meddled in Central America during the Cold War and as a result now faces a refugee crisis of its own on its southern border; the war in Iraq helped set the foundation for ISIS, and the U.S. withdrawal from that country unleashed its scourge on the world. The list of America’s unfinished business is long, and bloody. And it is growing longer.

With this withdrawal, the message the U.S. is sending is that it has failed once again, that the post-WWII international order it led—including NATO—failed and the emerging new world order will be interest-based and transactional. The subtext is that it’s okay to walk away from your commitments if your short-term national interests are not being served.

And that is a recipe for a world in chaos.