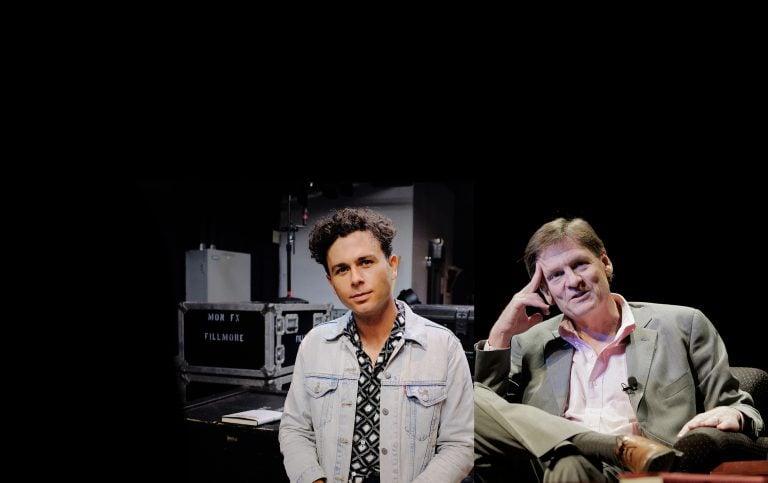

Max Kerman in conversation with Michael Lewis: On political worldviews and crafting stories

The Arkells frontman and the author of ‘The Fifth Risk’ and ‘Moneyball’ discuss American politics, the importance of good government, and the nature of the presidency

Michael Lewis (right) and Max Kerman. (Photograph by Mike DeAngelis; T.J. Kirkpatrick/Getty Images)

Share

Max Kerman is the frontman for the multi-JUNO Award winning band, Arkells.

A few years ago, after devouring his latest book, I became intent on finding a way to get in touch with New Orleans-born, best-selling author Michael Lewis, one of my favourite storytellers. He has a penchant for finding depth and humour in unassuming characters that I find so impressive. He’s so apt at finding “the story” hidden in the corners that three of his books—The Blind Side, Moneyball and The Big Short—have been turned into hit movies. His latest, The Fifth Risk, has only been out since Oct. 2, and its film rights have already been acquired by Barack and Michelle Obama under their Netflix production deal. (Lewis interviewed Obama for a long Vanity Fair profile in 2012.)

That knack for storytelling is important to me. As a songwriter, I look to tell stories about interesting characters, and although we operate in different mediums, Lewis is an inspiration in my work in the Arkells. His book Boomerang, about the 2008 global market collapse, helped inform some of the characters in songs from a previous Arkells record, High Noon (“Systematic,” “Fake Money”). When we were working on our latest album Rally Cry, the goal was to tell a story with characters that are full and vibrant and entertaining; Arkells lyrics, in a way, are experiments in reporting on my friends and community, and tracks like “Hand Me Downs”, “Only For A Moment”, and “Don’t Be A Stranger” were attempts at a profile in song. The non-judgemental worldview that appears in his work appeals to my sensibilities, too: When he writes, he isn’t black-or-white, or good-or-bad. In a time when it can be hard to document stories about American ambition—be it on Wall Street or in Silicon Valley or major league sports—he is able to tell a fully engrossing story with nuance and empathy. And as a student of the creative process, I have long been interested in how he works.

The Fifth Risk offers the spotlight to the type of person that typically doesn’t receive much shine: American government bureaucrats, specifically in the Department of Energy and Commerce, and the National Weather Service. Lewis was interested by the Trump administration’s lack of interest in how these parts of the government worked, and the chaos he found when he spoke to them “shocked him.” Like most Americans, he had no sense of how important and sophisticated these departments had become to ensure public safety. The Fifth Risk outlines what could happen when these departments are not tended to or managed correctly, and how large American populations could be in danger. It’s like my mother, Janet Kerman—a public high-school teacher who’s been espousing the virtues of good government work since I was a kid—would say: “You know, it’s a miracle that the garbage gets picked up on time every day, and the street lights still work.”

While I was on a tour bus in Dallas, I spoke to Lewis from his home in Berkeley, Calif., and we spoke about the modern political discourse, how we can incentivize people to work in service of their communities, his view of the American presidency, and how he chooses which stories to tell.

Q: Did growing up in New Orleans shape your world view and how you practice journalism?

A: Yes, probably it did. It informs how eager I am to express my views. I did grow up in a place where, whatever your political views were, were less interesting than how you expressed them. I wasn’t raised in an overtly political household. I was taught from an early age, that because everyone is supposed to get along, you don’t talk about religion and politics…because historically it’s a place that if you didn’t get along, you shot each other. So the price of not getting along is high.

The standard for entertainment is pretty high. People hold themselves to a high standard when they open their mouths. What comes out tends to be kind of interesting. It’s a very story telling kind of place. Why that is has a lot to do with how stagnant it is. You could tell a story about a bunch of people and know that everyone you’re talking to knew those people. Life on the streets has a narrative feel to it, in a way that life on the streets in Berkeley (California) does not.

The biggest effect of growing up in New Orleans has had on me is my attitude to the rest of this country. It is so different. It’s so distinctly not careerist or ambitious. It’s very family-oriented. Neighbourhood-oriented. And happy, when I was growing up. And when I collided with American ambition, I think I come at it from a different angle because my first step isn’t wanting to be in it. It’s to watch it and wonder.

Q: Were your parents curious people?

A: When my wife met my father, she said, “I didn’t realize I got the cheap imitation.” My father especially has a real feel for character. A real delight in the variety of character. I grew up listening to stories about people who were interesting. Funny stories that were not overtly judgemental.

Q: Compared to a lot of more prominent journalists, you don’t seem as judgemental and opinionated than some of your peers. You’re less inclined to put your personal opinions in your stories. Was this a conscious decision?

A: It’s not that I don’t have views. It may be that in the writing of the things, I find my own views, if I happened to express them, feel kind of tedious. They just kind of get in the way of the story.

But that’s also maybe slightly false. Maybe what I’m doing is embedding my views in the story in some kind of sneakier way. I find naked expression of views kind of boring.

Q: So, after writing The Fifth Risk, are you a big-government guy now?

A: It’s funny. I don’t think of it as big or small government. I’m a smart-government guy. I think we’re doing some really dumb things. I kind of think I want to empower people more, and reward people more. I want there to be upside. We’ve created a system where there is too much risk aversion…It’s not taking enough risk because it gets so severely punished to the point that its (government) existence is under threat when something goes wrong.

I’m a “change the incentives in government” guy. It may be smaller government if it was really well-ran. It would just be different. The reason I wrote the book, is nothing happens unless we change the narrative around it. People start seeing it as the solution as opposed to the problem.

Q: You talk about Trump and his team in The Fifth Risk, and his flaws as a president are quite obvious. But I’m curious how spending time with Obama and thinking about how he did his job make you think differently about any previous presidents?

A: Yes. Spending time with Obama while he was president made me more sympathetic to all of them. It’s the impossible job. Having said that, the thing that struck me that was so remarkable about Obama is that he hung in that job for eight years and wasn’t screwed up personally. Bush seemed inadequate to the job, but probably a really nice guy. Clinton, I think actually is psychologically a little goofy. I think its screwy getting blowjobs from interns in the Oval Office. That’s just crazy. And needy, in a way.

Whereas with Obama, you sit down with him and you feel like you’re with a extremely well-adjusted, normal, clear eyed person, who has not been warped by the office. And that is something that amazed me. Because if I was on the receiving end of the crap he was—or any of the others for that matter—I’d be so bitter and angry. I’d be looking to destroy people. It’s amazed he came out on the other end just as even keel as he went in.

Trump puts everyone in a different kind of release than Obama. What everyone had in common up to now, was a sincere interest in the welfare of the country. And they all had slightly different political views, but they are wrestled with how to do the right thing by the country. They’re thinking of someone other than themselves. They are thinking of the future.

Right now, we have someone who thinks of nothing but himself, and the next five minutes.

Q: I was thinking about The Big Short, and I don’t know if you meant to write it this way, but you see these guys who were able to buck conventional wisdom and take advantage the system, and they are portrayed in a heroic way. Of course, these people were very intelligent. But I’m curious: does this make them good people? What do you think about the characters in that story who were able to make a lot of money while the rest of the country was crumbling?

A: Couple things. One is, I was personally fond of all of them. Put that to one side: I liked them all. Secondly, intruding with my own view of them, I saw it as a huge literary opportunity. To have these characters who were huge successes in narrow terms—they made big pots of money. Readers would attach themselves to, and think of them as successes and heroes…but doing something and making their money in such a way that you could disapprove of them if you wanted to. I thought there was an opportunity to leave the reader in a constant state of discomfort, for rooting for these people to make their fortunes from the collapse of the society. So my mind stopped there. I didn’t have that much interest in my own moral view.

However, I do have a view. My view I think is, the function the short-sellers perform is actually a really critical function. If we had many more of them, and people actually listened to them, then the problem wouldn’t have got so out of hand.

They weren’t as simple as just mercenaries. Just about all of them made some, and in some cases great attempts to inform the authorities—either the financial regulators, or the FBI, or the news industry about what what was going on, because they were so disturbed by it.

To the extent I would disapprove of anything they did, it’s so trivial compared to my disapproval of the people who caused the problem.

Q: You’ve written a lot about the industries in which the best and brightest end up: Wall Street, Washington D.C., Silicon Valley. But you haven’t written about education and the system that trains these people and gives them their credentials. In your Princeton commencement speech, you talk about how the graduates owe a debt to the unlucky. Do you ever plan on writing about the education system, and how it works in America?

A: There are all of these big systems that would naturally invite the interest of an author—the healthcare system, the education system, the federal government. The problem is: how do you carve a story out of them? I wouldn’t even know were to begin, in creating a narrative that would begin to inform us about that system.

I do have thoughts, though. I think the system has evolved, and sort of squeezed out of itself, a sense of noblesse oblige. The Princeton motto is “Princeton in the nation’s service.” It goes back like 200 years. There was a time for Princeton students, when one of the most desirable courses of study was public administration: there was an idea where you’d go into public service when you came out of Princeton. That’s all withered and died, and in its place has risen departments of financial engineering.

At the same time, the old-fashioned elitist admission system has been replaced by a meritocratic one. And the kids who get in are now even less inclined to think that someone has done them a favour, that they owe something to the society because they have been gifted this position. Instead, they say “I’ve worked my ass off for this, and I don’t owe anybody anything. Whatever I get, I’m owed.”

Coupled with, you have many more people that go to schools like Princeton that need to take out loans to go there, and so when they come out the other end they don’t have much choice but to go make money. Or at least it’s harder not to take the job at Goldman Sachs.

I do think the system of higher education has gotten at cross-purposes with the rest of the society. It has gotten really good at generating people who go out and do really well for themselves inside of screwed-up systems, and less good at creating public spirited leaders.

But this is by degree. It still generates those kinds of people, but the pressures have gone the wrong way.

Q: Do you know the book Winners Take All, by Anand Giridharadas, which just came out?

A: Funny you say that—I just bought it! I will read it. What he’s on to, it sounds like to me, is the same thing that Steve Bannon was on to. This feeling that elites have betrayed the society. Or this feeling that they have somehow become detached from the society.

Q: Well, he gets in to the idea of incentives and how young people who are finishing up a degree never have an opportunity to go in to public service. I think you’d enjoy it. It’s a little more prescriptive than what you’d typically write.

A: I never go in thinking I’m going to solve the problem. I don’t feel comfortable in that role. I’ve always felt more interested in other things than fixing problems.

Q: You’re consistently able to write about something seemingly broad—like the national psychology of a country like Greece or Iceland—without seemingly ever getting accused of over-generalizing people. How do you ensure that you’re not painting with too-broad strokes? How do you respond to blowback from, say, Greece and Italy?

A: You can’t write anything people like without other people not liking it. Nobody I wrote about liked the description of themselves. And the only people who actually embraced the description of themselves that I offered were the Irish. Because the Irish are the one group left that wallow in their cultural stereotype. The Greeks were a little bit of an exception, because the bottom of the Greeks’ story is Greeks’ mistrust of other Greeks. When Greeks responded to it, they responded with enthusiasm because they thought I was talking about the other Greeks.

The Icelanders feel like: “You’re not allowed in our country anymore.”

Q: As you’re writing, do you ever consider if a given book is going to be a hit, or turned into a movie?

A: The opposite almost. My experience with the movie industry has been so quixotic. Two of the three books that have been made are so obviously not movie material. The experience I’ve had is that the more you make a book to be not like a movie, the more likely it is to become one. So don’t worry about it!

I judge the intensity of my own feelings on the subject. The more that I care about the thing, the more likely it is that other people are gonna care about the thing. The only way I can monitor the future market of the book is just by monitoring my own feelings. If I’m enthusiastic about something, the rest will take care of itself.

This conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.