Regionalism is nothing new

Scott Matthews: Politics are not significantly more regionalized today than they were in 2015. But Quebec is the anomaly.

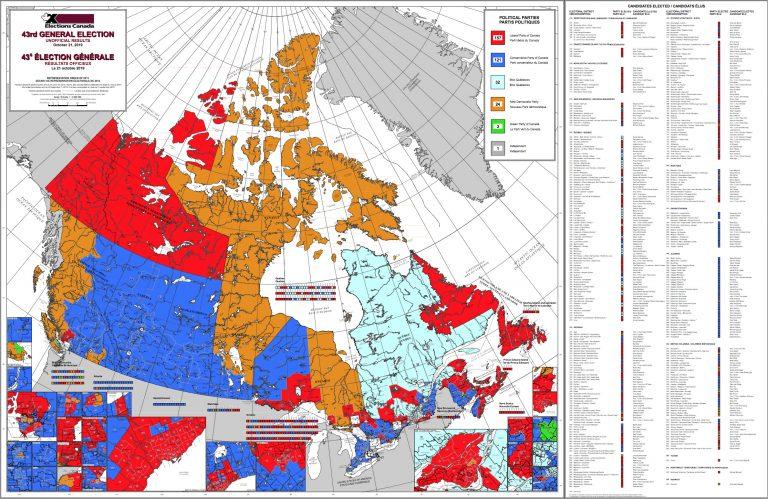

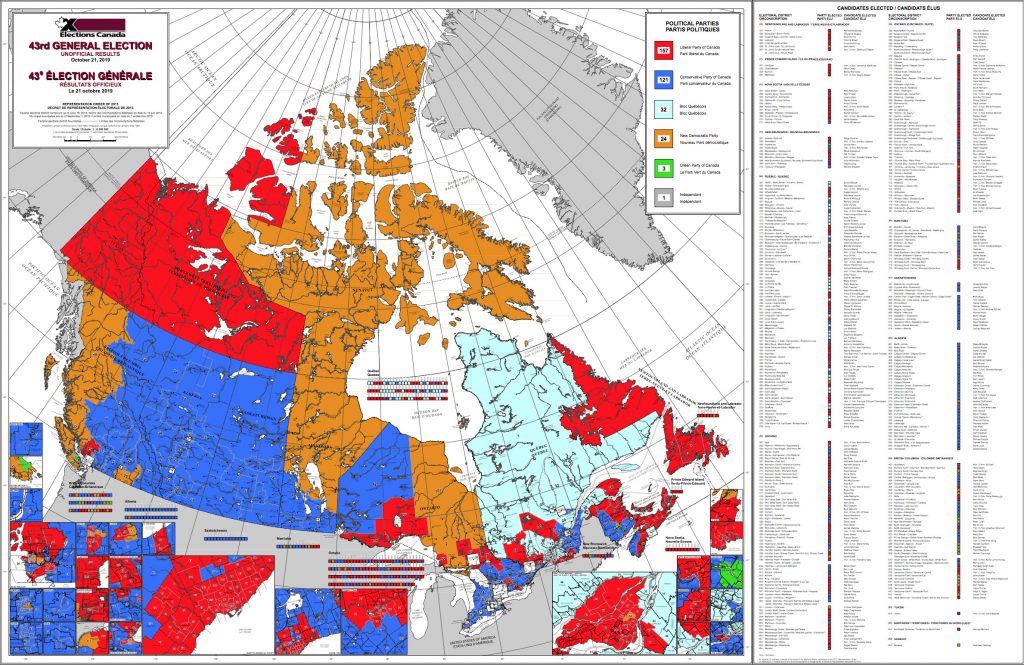

(Elections Canada)

Share

Scott Matthews is an associate professor in the department of political Science at Memorial University of Newfoundland.

A prominent theme in the wave of commentary on last week’s election is Canada’s increasing regionalism. Indeed, it’s hard not to see a reflection of the highly fragmented politics of the 1990s in the outcome of Oct. 21, 2019, particularly looking at the colouring of Elections Canada’s map of national results.

Canadian politics has always been highly regionalized, of course. Nevertheless, talk of increasing regionalism in this country seems largely—though not entirely—bogus. At least that’s the sense that one gets has after looking carefully at the pattern of change in the parties’ provincial seats and vote shares between 2015 and 2019.

The first critical point is that the 2019 election’s overall dynamics were decidedly national. The Liberals lost votes in every province. Likewise, Liberal seats were lost everywhere but Prince Edward Island, where the party saw no change in its total seats. Conversely, the Tories gained or held on to their seats in every province but Quebec (where they went from 12 to 10). The party also gained vote share in every province, save, again, for Quebec (where their vote share was basically unchanged [a drop of -0.7 per cent]) and Ontario (a drop of 1.8 per cent).

In general, it appears that Tory gains were made at the Liberals’ expense. The correlation between Liberal and Conservative vote shares at the provincial level was strongly negative: by the standard statistical metric, Pearson’s r (otherwise known as the Pearson correlation coefficient), the correlation was -.73. As Tory gains increased, so did Liberal losses.

Using regression analysis, a statistical technique that allows us to summarize the nature of the change, we find that for every one point in provincial vote share the Tories gained, the Liberals lost over three-quarters of a point. (Controlling for the NDP, this shrinks to about two-thirds of a point.) The finding is similar at the seat level: for every Tory seat gained, the Liberals lost half a seat on average, holding constant NDP gains.

If the dynamics were regional, these correlations would be weaker: Liberal losses in a given province would elevate the fortunes of different parties in different provinces. The overall pattern suggests—consistent with most pre-election analysis—that there were strong national headwinds facing the Liberals in this election, and that these headwinds operated pretty much everywhere. The results suggest that those headwinds operated generally to the benefit of the major national parties, particularly the Tories.

As noted, Quebec is a partial exception to the general pattern. The electoral recovery of the Bloc Quebecois is a clear sign of increasing regionalism. But importantly, today’s Bloc is in a very different place compared to the strong position the party occupied in the 90s. The Liberals remain, as they were after 2015, the largest party in Quebec (though they lost 5 seats). The Bloc’s success was largely a reflection of the NDP’s collapse in the province, with the Liberals and Tories only lightly affected. Thus Quebec is about as well represented in the major national parties as it was before the election. This is vastly different from 1993, when the BQ had nearly triple the seats of the Liberals and 54 times the seats of the Progressive Conservatives (they had only one seat).

What about the West? Notwithstanding the obvious national dimensions of the election, we might worry that the Tories’ gains and Liberals’ losses in the West will change national politics in a regionalizing fashion. Perhaps the Tories will be more influenced by “Western concerns” and the Liberals more influenced by “Eastern concerns.” Anything is possible. But the Tory caucus isn’t much more Western than it was before the election. The share of the party’s caucus that is from the four Western provinces has grown since 2015, but only from 55 to 59 per cent.

Is the Liberal caucus more dominated by the East? Again, not really: the share of the party’s caucus east of Manitoba has increased to 89 per cent, but it was already very high, at 83 per cent. To be sure, the Liberals lost four seats in Alberta and one in Saskatchewan, and it is worrying that these provinces have no representation in the governing party’s caucus.

That said, I’m dubious that there’s a critical difference, in representational terms, between five MPs (less than 3 per cent of the Liberals’ caucus following the 2015 election) and zero MPs. Put differently, it’s not just this week that the Liberals’ seem challenged to represent Alberta and Saskatchewan.

Looking at the change in the pattern of seats and votes, it’s hard to sustain the view that the country’s politics is considerably more regionalized today than it was after the 2015 election; Canadian regionalism is nothing new.