Screaming into silence

Cindy Blackstock: I believe those little spirits buried on the grounds of residential schools came to ensure the work gets done to end the injustices facing survivors

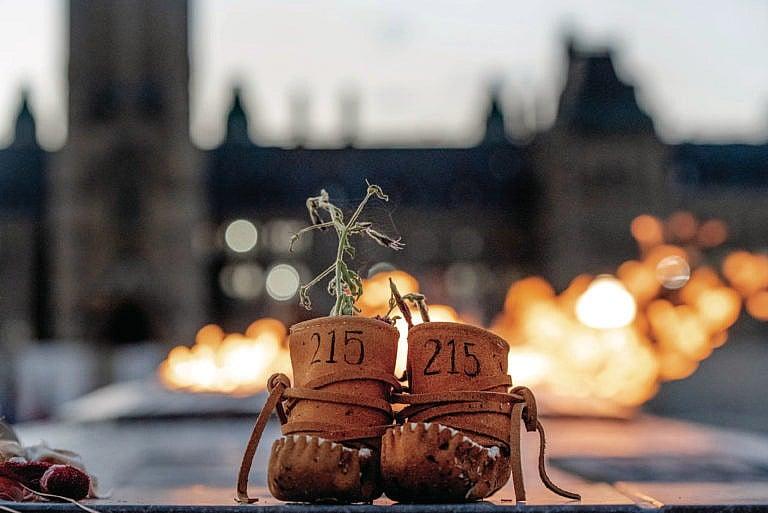

Memorial to residential school victims outside Parliament Hill in Ottawa. (Shelby Lisk)

Share

Cindy Blackstock, a member of the Gitxsan First Nation, is the executive director of the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada and a professor at McGill University.

Residential school survivors knew where the children were buried because some of them had dug their graves. They told their truths to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and gave the country a national plan in their 94 calls to action for ending the injustices facing this generation of First Nations, Métis and Inuit children, and to ensure nothing like this happens again. Some of us heard them, but what they said was too confrontational for most—so people called them “stories” and looked away. The survivors must have felt they were screaming into silence.

The buried children died afraid and alone—away from their families—in “schools” that were more akin to re-education camps, run by the Canadian government and the Christian churches from the 1830s to 1996. Many could have survived if public will had forced Ottawa to implement the life-saving reforms posited by Dr. Peter Henderson Bryce, the chief medical health officer of the Department of Indian Affairs in 1907. Bryce found that tuberculosis was ravaging the malnourished children at 20 times the rate of others, fuelled by dramatically unequal “Indian” health funding and poor health practices. As the 1907 headline of the Evening Citizen reported, there was “absolute inattention to the bare necessities of health” and the schools were “veritable hotbeds of disease.” Other newspapers wrote that the children were “dying like flies,” compelling lawyer Samuel Hume Blake to say in 1908, “In that Canada fails to obviate the preventable causes of deaths, it brings itself into unpleasant nearness to manslaughter.”

READ: What I told my child about the Kamloops graves—to honour the 215

Canada refused to implement Bryce’s reforms and pushed him out of the public service in 1922 for refusing to stay quiet. That same year, Bryce walked onto the premises of Ottawa bookseller James Hope & Sons with his pamphlet, “The Story of a National Crime.” More headlines followed, but then the story died—and so did the children. Bryce died in 1932 and he was erased from Canada’s history. His family says his greatest lament was that “the work did not get done.” He must have felt like he, too, was screaming into silence.

First Nations, Métis and Inuit parents often spoke up but were ignored, and many were arrested for refusing to send their kids to these death traps. While the parents were in jail, the government took the kids. Over the decades, people of all walks of life regularly peppered the federal government with reports of child abuse, neglect and death in residential schools. Canada just waited out the media storm and continued business as usual.

I was born in 1964 in northern B.C. I could have been in one of those schools, but I was spared. I remember being the only “Indian” kid in my classrooms and wondering where the other Indian kids were. The townspeople had an answer for that—Indians were too dumb to learn, were drunks and would just grow up to be on welfare.

I began to hear the truths about residential schools decades later. At first only faintly, and then with growing strength as survivors told their truths, with great pain, so they could make sure this never happened to their grandchildren. It all made sense: why so many numb the pain with alcohol and drugs, why others disappeared and died amid deafening public silence. The government’s colonial project was made possible by purposefully feeding the populace a steady diet of distractions, misinformation and stereotypes.

The Prime Minister talks about the horrors and injustices in the past tense—probably to avoid any accountability for the serious harms the government continues to foist on this generation of First Nations, Métis and Inuit children.

Canada used the Indian Act to drive kids into residential schools, and it is still in force. The country says I am a “status Indian.” I have a card saying so, but it expired decades ago and I don’t plan on renewing it. I want no part of Canada’s racist game.

Yet I am a player in this wicked colonial game, and so are you. The Indian Act is still around despite a royal commission laying out a 20-year plan to get rid of it in 1996 and the public service inequities that Bryce pointed out more than a century ago.

One hundred years after Bryce’s report, the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society and the Assembly of First Nations filed a human rights case against the federal government. Canada fought the case tooth and nail, relying on legal technicalities bereft of any serious consideration of how the inequities were affecting Indigenous children being separated from their families and placed in foster care at higher rates than in residential schools, experiencing irremediable harm and, in some cases, death. In 2016, the Human Rights Tribunal ordered Canada to immediately cease its discriminatory conduct. The government welcomed the decision and then did not comply. The tribunal has been forced to issue 19 further orders and has linked Canada’s ongoing non-compliance to the unnecessary foster placements of many kids and to the deaths of three.

I used to know how much children’s caskets cost because I had to raise funds for them so often.

Canada did not kill the kids directly—it put them in situations where their deaths were far more likely. Children like Jordan River Anderson, who died in a hospital in 2005 at age five never having spent a day in a family home because Canada and Manitoba were fighting over payment for his at-home care due to him being First Nations. Or like 15-year-old Shannen Koostachin, an inspiring Cree education leader who fought her whole life for “safe and comfy schools” for First Nations students before dying in a 2010 car accident, hundreds of miles away from her family because there was no high school in her community. Then there were the seven First Nations youths found in a river in Thunder Bay, Ont., after they’d gone there for high school because Ottawa was too cheap to build one near their home communities. Not every child died, of course, but others have never seen clean water come from a tap or grew up in foster care at 14 times the rate of other children due to the multi-generational residential school trauma and inequitable federal public services.

In mid-June, federal ministers who have worn orange shirts and orange ribbons held news conferences about “allowing” First Nations names on Canadian passports and, more substantively, passing the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples into Canadian law. I could not view those conferences because I was in Federal Court watching Canada’s lawyers try to overturn two tribunal orders requiring it to compensate First Nations children it had discriminated against (and they are still children) and to avoid paying for public services for Indigenous kids off-reserve and without Indian Act status. I also attended a news conference with survivors from St. Anne’s residential school in northeastern Ontario who wanted the federal government to drop its legal battle against them. That school actually had a homemade electric chair for punishing students.

I believe those 215 and 715 little spirits buried on the grounds of the Kamloops and Marieval residential schools came to ensure the work gets done. We need to keep talking to the elected officials about the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, even if we think they are not listening, because ultimately they will all hear us in the voting booth.

This article appears in print in the August 2021 issue of Maclean’s magazine with the headline, “Screaming into silence.” Subscribe to the monthly print magazine here.