The Britain I knew is lost

Michael Coren: This once resilient country is in a state of crisis, sinking in a national mood of powerlessness and indifference

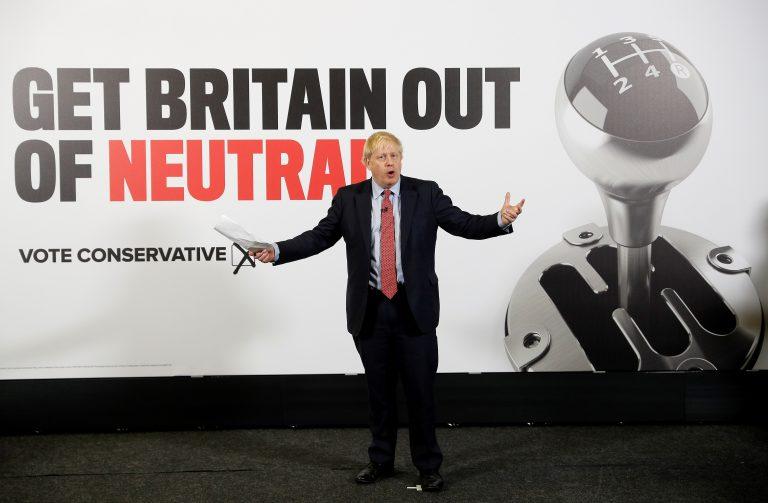

Johnson poses with a Conservative Party campaign poster at the Kent Showground in Detling, southeast England, on Dec. 6, 2019. (PETER NICHOLLS/POOL/AFP via Getty Images)

Share

I left Britain when I was 28-years-old, and return every year for extended visits. A number of my friends from university are senior MPs and journalists, while others do all sorts of jobs outside of public life. What unites them at the moment, however, is a deep sense of gloom and pessimism that I have never seen before.

The country has faced major unemployment, war, mass strikes and prolonged terrorist campaigns, but people weren’t as despairing as this. It’s as though the oxygen of hope has been sucked from the national discourse.

This emotional and political miasma became most obvious after the Brexit vote, when half of the country was incredulous at the result, shocked that what was considered a non-contest, and merely a cynical move by then Prime Minister David Cameron to silence his party’s right-wing, had resulted in the removal of Britain from the European Community, the most successful political project in living memory.

It’s all been solidified by an election campaign—the vote will take place on Dec. 12—where some of the least impressive leaders in the country’s history do battle, less for a shining trophy than a poisoned chalice. Whoever is prime minister in a few days will have to secure the country’s exit from Europe, with all of the troubles, humiliations and losses that are inevitable.

Boris Johnson and the Conservatives are likely to win, but while some polls have him as several points ahead, the informed prediction is of a slim majority or even another hung parliament. Johnson is able but untrustworthy, considered to be selfish and erratic, and while North Americans may often find him charming, in Britain he’s regarded more as a dishonest if intelligent buffoon. But, many will argue, at least he’s not Jeremy Corbyn.

READ MORE: Canada’s Brexit talks with the U.K.: There are none

The opposition Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn is a hard-left veteran who all through my youth was seen as the perennial eccentric, allied to any number of Marxist, Irish republican, anti-Israel and fringe positions. Nobody took him seriously as a potential leader; until, that is, he became leader. His victory encouraged large numbers of militants to join the party, bringing with them a bullying and sometimes sinister approach that is severely intolerant of criticism or contrary opinion.

This has been particularly poisonous around the subject of Israel and Palestine, with criticisms of the Jewish state going far beyond anti-Zionism. I don’t believe that Corbyn is an anti-Semite but I do believe that he lacks knowledge of and empathy with the Jewish narrative, and has allowed authentic Jew-haters to remain in his party.

Even The New Statesman, arguably the most respected left-wing magazine in Britain, stated in an editorial that, “The essential judgment that must be made is on Mr. Corbyn himself. His reluctance to apologize for the anti-Semitism in Labour and to take a stance on Brexit, the biggest issue facing the country, make him unfit to be prime minister.” For that publication to not endorse the Labour leader is breathtaking.

The Liberal Democrats, led by the profoundly uninspiring Jo Swinson, should be attracting all sorts of people appalled by both Tory and Labour, but she and her party have found themselves marginalized rather than legitimized. The party has never fully recovered from forming the governing coalition with David Cameron’s Conservatives, and may well become a mere parliamentary rump.

Brexit dominates the discussion, and nobody has any answers beyond the sound bite and the platitude. The fifth-largest economy in the world is now committed to European withdrawal, but because the decision was so unexpected, and so influenced by emotion and distortion, no politician has a viable plan to implement it all with anything close to stability and calm.

The background to all of this is an austerity program introduced by the Conservatives that has devastated the country. The National Health Service is under-funded and at a breaking point, economic recovery is at an all-time low, food banks are used more than ever, and the number of people sleeping in the streets has increased by 169 per cent.

Obvious wealth co-exists with tangible poverty, knife crime is endemic in parts of the inner city, and there is an increasing division between London and the rest of the country, and between those who have benefited from economic globalization and those who have become its victims.

So the malaise is partly existential, in that there are genuine challenges and problems, but the crisis goes deeper than that. Enemies have always existed, from the ghouls of Nazism in the 40s to the hardships of economic decline of the 70s, but they always seemed to not only bring out some of the best in British society, but also to appear temporary and able to be overcome. That feeling, impossible to strictly quantify, has disappeared. The British complain—it’s a national fetish—but never with such genuine pessimism and resignation as they do now.

One of my oldest friends, a former MP and respected social commentator, describes it as “a cult of powerlessness and a culture of indifference.” In other words, people assume that what is going on is beyond them and cannot be changed, they are disgusted at the lack of leadership, and this leads to a form of apathy.

We’ll know a little more after the election and a lot more after Brexit is delivered—though it could take a long time—but this is not the country I knew. That’s not nostalgia or middle age speaking, that’s a gritty and informed reality, and said with more sorrow and pain than I can properly express.