The next big threat facing the Trudeau Liberals: China

Stephen Maher: China’s increasing belligerence will require a tougher tone from Ottawa. The fate of the Liberal government may depend on it.

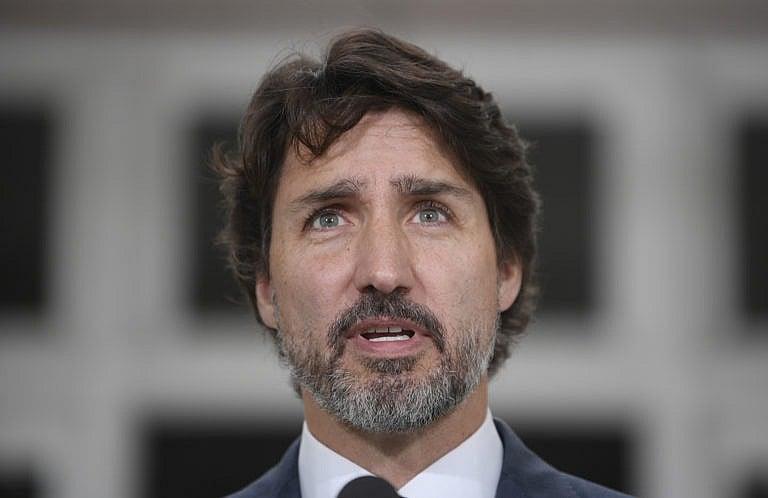

Trudeau responds to a question about China during a news conference outside Rideau Cottage in Ottawa on June 25, 2020 (CP/Adrian Wyld)

Share

If you were to make a list of all the people who stand between Justin Trudeau and the majority government he dreams of, you’d have to put Xi Jinping, not Erin O’Toole at the top.

Trudeau looks like he is ready for a winning election campaign in the spring of 2021, but the president of China poses a real political threat.

Otherwise, things look pretty good for the Liberals. If the vaccine rollout continues to go well, Canadians are likely to be in a good mood this spring. The Liberals can likely keep borrowing, and many people have been hoarding cash, so with any luck at all, we will be optimistic, getting vaccinated, spending money and feeling cheerful—the kind of mood incumbents like.

The inauguration of Joe Biden will make many things easier, in part because of a shift in the consensus about fossil fuels, which will decisively undermine business-as-usual arguments from the oil patch. This shift has already made it easier for Trudeau to put out a more ambitious climate plan, which suggests the Liberal middle path on the file is politically sustainable.

On Indigenous affairs, the Liberal record is weaker, but they have made real but slow progress on some practical files, like Indigenous policing and water, and can point to their commitment to pass the United Nations Declaration on the rights of Indigenous Peoples.

None of the Prime Minister’s opponents in Ottawa and the provincial capitals look especially dangerous at the moment, and the prospect of an election should keep his party in line. His most likely successor, Chrystia Freeland, is just getting her feet wet at Finance, so there is no longer reason to wonder, as there was during earlier scandals, that the party might want to knife him.

O’Toole is more competent than his predecessor, but his attacks on Trudeau’s management of the pandemic have so far failed to connect.

But O’Toole has one winning message: Trudeau is soft on China.

Jinping has kept Michael Kovrig and Michael Spavor as hostages for two years. His diplomats have repeatedly, arrogantly attacked Canada and used underhanded trade tactics to put pressure on Ottawa, all in a vain attempt to win the release of Meng Wanzhou, who is under house arrest thanks to an American extradition request that Canada was legally obliged to honour.

This pressure is in keeping with China’s newly assertive foreign policy, which appears to mark a new phase for the traditionally inward-looking society.

For decades, as China became the industrial powerhouse of the world, Beijing played nice with its customers in the West and the West played nice with Beijing, as both sides enjoyed the music of the ringing cash registers.

No more. China has a new approach because it has convinced so many countries to join the Belt and Road Initiative—a transportation infrastructure plan linking Chinese factories with materials and markets around the world.

The network of ports and roads—built with Chinese capital and know-how—will connect about 60 countries, representing about two thirds of the world’s population, creating a sphere of influence that will make China a more potent threat to the Western dominance than the Soviets were.

The Chinese are using what they call “wolf warrior diplomacy” and economic muscle to project power outside that web of belts and roads. This explains the insulting tone repeatedly taken by Cong Peiwu, the Chinese ambassador to Canada, and it explains why Canadian canola, pork and lobster exporters keep running into problems.

It could be worse. We could be Australia. The Aussies are paying a heavy economic price for asserting their independence. There are ships off China right now carrying $500 million worth of Australian coal that the Chinese have decided they don’t want.

Chinese-Australian relations soured in 2018, when Australia introduced the Foreign Influence Transparency Scheme Act—aimed at revealing and stopping foreign attempts to meddle in Australian politics.

There is a pattern of Chinese “influence operations” around the world that we can’t afford to ignore.

A disturbing recent book, Hidden Hand, lays out a picture of these operations, including the use of honey traps—where young Chinese women get close to politicians. Consider California congressman Eric Swalwell, who is under pressure to resign after news broke about his relationship with a suspected Chinese spy who romanced middle-aged politicians across the Midwest. Canadians may recall that in 2011 a parliamentary secretary to then-foreign-affairs-minister John Baird had to apologize after a friendship with a young Chinese reporter was revealed.

Just as worrying, and far more common, is state-sanctioned industrial espionage—remember when we used to have a company called Nortel?—and secret commercial arrangements made with officials and politicians.

Recall that in 2010, Canadian Security Intelligence Service director Richard Fadden warned that some Canadian politicians were too close to certain unnamed foreigners.

“We’re in fact a bit worried in a couple of provinces that we have an indication that there’s some political figures who have developed quite an attachment to foreign countries,” he said. “The individual becomes in a position to make decisions that affect the country or the province or a municipality. All of a sudden, decisions aren’t taken on the basis of the public good but on the basis of another country’s preoccupations.”

Although this worries Fadden, it doesn’t seem to bother Trudeau. In 2013, he famously spoke of his admiration for China: “Their basic dictatorship is actually allowing them to turn their economy around on a dime.”

In 2016, he attended a fundraiser with a Chinese billionaire who donated $1 million in Pierre Trudeau’s name, including $50,000 for a statue.

Pierre had deep connections to China. He first travelled there in 1949, during the Communist revolution, and established diplomatic relations in 1970.

He was also close to Quebec’s powerful Desmarais family, who have strong connections in both countries. They have close business and family ties to Trudeau senior, Brian Mulroney and Jean Chretien. Michael Sabia, Trudeau’s new finance deputy minister, is close to the family, as are many former Liberal politicians.

The Canadian foreign policy establishment has long sought to link our resources and Chinese factories to help reduce our dependence on American trade. It has worked, at least to some extent. Chinese markets and investment have helped Canadian farmers, loggers, miners and fishermen, and nobody who has recently been to Toronto or Vancouver can doubt that we have benefitted from Chinese money and vitality.

But as China becomes more assertive, even belligerent, Canada may need to take a new tone. Polls show that Canadians do not want their government to be passive in the face of Chinese hostage-taking.

Foreign issues rarely decide elections, but they can contribute to voters’ impression of a leader, which is what decides elections. If Trudeau seems to be putting the interests of his buddies in the Laurentian elite ahead of the interests of the two Michaels it could help portray Trudeau as his Conservative opponents want voters to see him: out of touch with regular Canadians and acting for his Montreal cronies.

O’Toole keeps hitting Trudeau on China, likely because it is one issue where majority opinion is closer to the Conservatives than the Liberals.

So if the Liberals are smart, which they are, we can expect a reset in the new year, a tougher tone, if only to blunt O’Toole’s attacks ahead of an election.

It would be comfort if we can see a vital national interest—sovereignty—at the heart of a new policy. With any luck, a Biden presidency will clear the air and bring the temperature down. But if it doesn’t, Canadians had better be prepared to take steps to protect our independence from foreigners intent on bullying us.