The next step for Canada: decriminalize hard drugs

Stephen Maher: Legalizing marijuana should lead Canada to tackle a more pressing challenge—ending the deadly and cruel war on drugs

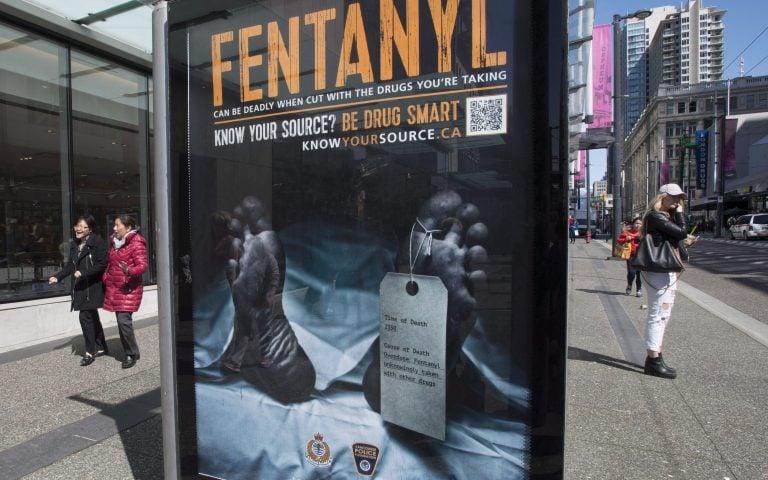

An anti-fentanyl advertisment is seen on a sidewalk in downtown Vancouver, Tuesday, April, 11, 2017. (Jonathan Hayward/CP)

Share

Canadians took a big step toward a less stupid society on Wednesday when we ended marijuana prohibition, which may allow us to now turn our minds to a more difficult but important challenge: decriminalizing hard drugs, which would allow us to tackle the opiate crisis more effectively.

There is a powerful argument for moving toward the kind of system they have in Portugal, where treatment, not punishment, is the priority for dealing with addiction, but politics is the art of the possible, and continued progress on drug liberalization here and around the world may depend on the political fallout from this first step.

Canada is the first country of note (sorry, Uruguay!) to legalize recreational marijuana, which means that we might think we know what will happen now, but we can’t be certain. The smart money seems to be on not a whole lot.

In question period on Wednesday, Conservative Leader Andrew Scheer led off with questions about the prosecution of Vice-Admiral Mark Norman, which suggests that Conservative strategists do not see a backlash to legal weed as a vote-winning opportunity to be preemptively framed as a reckless move by pot-loving Liberals.

The Conservative line of attack is that the Liberals have proceeded incompetently—always a safe assertion for an opposition party to make—not that legalization is in itself a terrible idea.

READ MORE: Cannabis is legal. Now about those pardons for pot possession?

This suggests that Scheer and his party sensibly recognize that this is an idea whose idea has come and that, as with gay marriage, their opposition to a more liberal law will dissipate like a puff of bong smoke in an October breeze.

It is possible that there will be unanticipated negative consequences. Perhaps people will get high more often than they do now and waste time playing video games. Perhaps there will be new problems with impaired driving.

Doctors are worried about the health effects of increased use, and there is no doubt that some users can experience anxiety and other ill effects, whether the product they are smoking is legal or not.

On the other hand, there is reason to believe that it helps with many health conditions, although not in a way that profits the pharmaceutical companies that influence public debates on this kind of thing.

I suspect that most people who want to smoke marijuana already do so, that it’s not the kind of decision that is greatly influenced by the Criminal Code, so we should stop wasting time and money penalizing people for a victimless crime, particularly when there is reason to believe the law is enforced unfairly along racial lines.

Racial politics have long poisoned our debates about drug policy. The initial public pressure for Canada’s marijuana prohibition came from Emily Murphy, a suffragette and white supremacist who, in the 1920s, warned in the pages of an otherwise excellent Canadian news magazine that the drug would lead to the despoilation of the white race by crafty Chinese pushers.

The demonization of minorities and political foes has been a feature of the drug war from the beginning. President Richard Nixon, who ramped up a pointless, violent and wasteful interdiction campaign, wanted to gain political advantage by targeting blacks and hippies, according to a former aide, and even the Clintons sought political advantage with drug war rhetoric.

Canadian politics is, of course, influenced by the harsh American anti-drug messaging, although we have never waged the war on drugs with the same level of inhumanity.

That American influence might make it harder to take the desirable next step, which would be to pursue a policy like the one in Portugal, where hard drugs have been decriminalized and the government tries to help addicts rather than throwing them in prison.

We have excellent reasons to change our approach. We are losing thousands of Canadians to accidental opiate overdoses every year, an accelerating crisis that is steadily spreading misery.

If the police were able to prevent this, they would have already done so. Fentanyl is insanely profitable. You can lock up as many people as you want and it won’t slow it down a bit.

Legislators and public health officials need to focus on harm reduction, preventing addiction by handling prescription pads more carefully for people who are not addicted and providing better treatment for people who are addicted, even if that means treating their addiction as something they must live with, rather than beat.

Locking up addicts and dealers is a waste of resources that we could use to deal with the problem. We should stop. The problem is that approach feels wrong to many voters because it seems to sanction drug use. They would prefer to feel virtuous while the bodies of addicts keep piling up.

Legal weed offers an opportunity to change the public’s thinking about this kind of question. The main initial impact of weed legalization is that Canadians will more conveniently acquire soft drugs they used to buy from dealers. That’s great, but the best outcome we can hope for is if leads to the end of the long, wasteful and inhumane war on drugs.