A budget for make benefit glorious economy of Canada

Budget 2017 shows how deeply the Trudeau government believes there are levers and buttons it can push to direct the economy

(Shutterstock)

Share

The very first table you come across when reading the Trudeau government’s 2017 budget isn’t about tax changes, spending measures or the Canadian economy at all. Under a section titled “The case for innovation,” Table 1 compares the five most valuable U.S. companies in the years 2001 and 2016. The biggest companies back then were mostly stuffy giants like General Electric, Exxon, Walmart and Citi—the budget’s authors managed to refrain from labeling them “old economy” companies, but that was clearly the intent. The “new” economy, then, is a digital one, as characterized by the big five in 2016: Apple, Google, Microsoft, Amazon and Facebook. There’s even a footnote to tell you those are technology companies, in case you still don’t get it.

The accompanying message: the world is changing fast, but fear not, this government knows “what Canadians need to succeed in an evolving economy.”

From that point on, budget 2017 more or less unfolds as a central planner’s instruction manual For Make Benefit Glorious Digital Economy of Canada.

READ MORE: Your one stop shop for Budget 2017

Back in 2015, as the Trudeau election campaign was gathering steam, some wondered how long it might take a Trudeau government to realize the economy doesn’t come with a set of levers and buttons that you push and pull to guide its speed and direction. But the budget released Wednesday was a full-on embrace of 1970s-style industrial policy—a verboten term for decades in federal politics—reflecting just how deeply the Trudeau team believes those levers and buttons exist.

In the budget there are bold vows—oddly reminiscent of China’s annual edicts for economic growth rates—about boosting exports by 30 per cent in the next eight years (even though exports have climbed just 2.9 per cent from eight year ago). It calls for clean technology to become a bigger share of GDP. The government even set a target for its “innovation and skills plan” of creating 14,000 new, high-growth companies by 2025.

And how shall all this come to pass? Specific industries were name-checked as priorities for government attention: advanced manufacturing, agri-food, clean technology, digital industries, health/bio-sciences and clean resources. Hundreds of millions will go towards creating a “venture capital catalyst initiative.” The government’s many varied and overlapping innovation programs will be streamlined to better assist the busy entrepreneur on the go.

Meanwhile Ottawa’s economy planners want to guide the creation of “innovation superclusters” across Canada—areas with a high concentration of businesses focused on particular industries (see the list of Chosen Ones above), situated alongside universities and overflowing with talent. Think Silicon Valley, the go-to region that every government the world over, including this one, believes can be replicated at home, if they just put their minds and enough resources to it.

It’s easy to draw a line between this strategy and the lads and lasses at McKinsey & Co. The global consulting giant makes its living telling other companies, governments and organizations how to be more innovative, and right now McKinsey is run by a Canadian, Dominic Barton, who also heads Ottawa’s Advisory Council on Economic Growth. Indeed, from the budget’s highly-produced cover—complete with a suitably diverse array of Canadians and overlaid with hand-drawn illustrations—down to the innovation jargon slathered throughout its pages, the budget could easily be mistaken for one of the firm’s high-priced consulting reports.

RELATED: Why McKinsey & Co. is helping Ottawa out, pro bono

The word “superclusters,” for one, might almost require a trademark symbol beside each mention. In last year’s budget the concept of targeting specific regions to encourage innovation was introduced, but back then they were simply referred to as “clusters.” But McKinsey consultants have spanned the globe preaching the gospel of superclusters with great urgency. Just this past December McKinsey produced a primer—no doubt required reading at Innovation Canada—on how to spur the region between Toronto and Waterloo to “global technology supercluster status” like, you guessed it, Silicon Valley, but also Berlin and Tel Aviv. (Budget 2017 uses the same cities as examples.) “The opportunity is there,” the McKinsey report notes, “but the window could be closing quickly.”

Act fast, this great offer won’t last long.

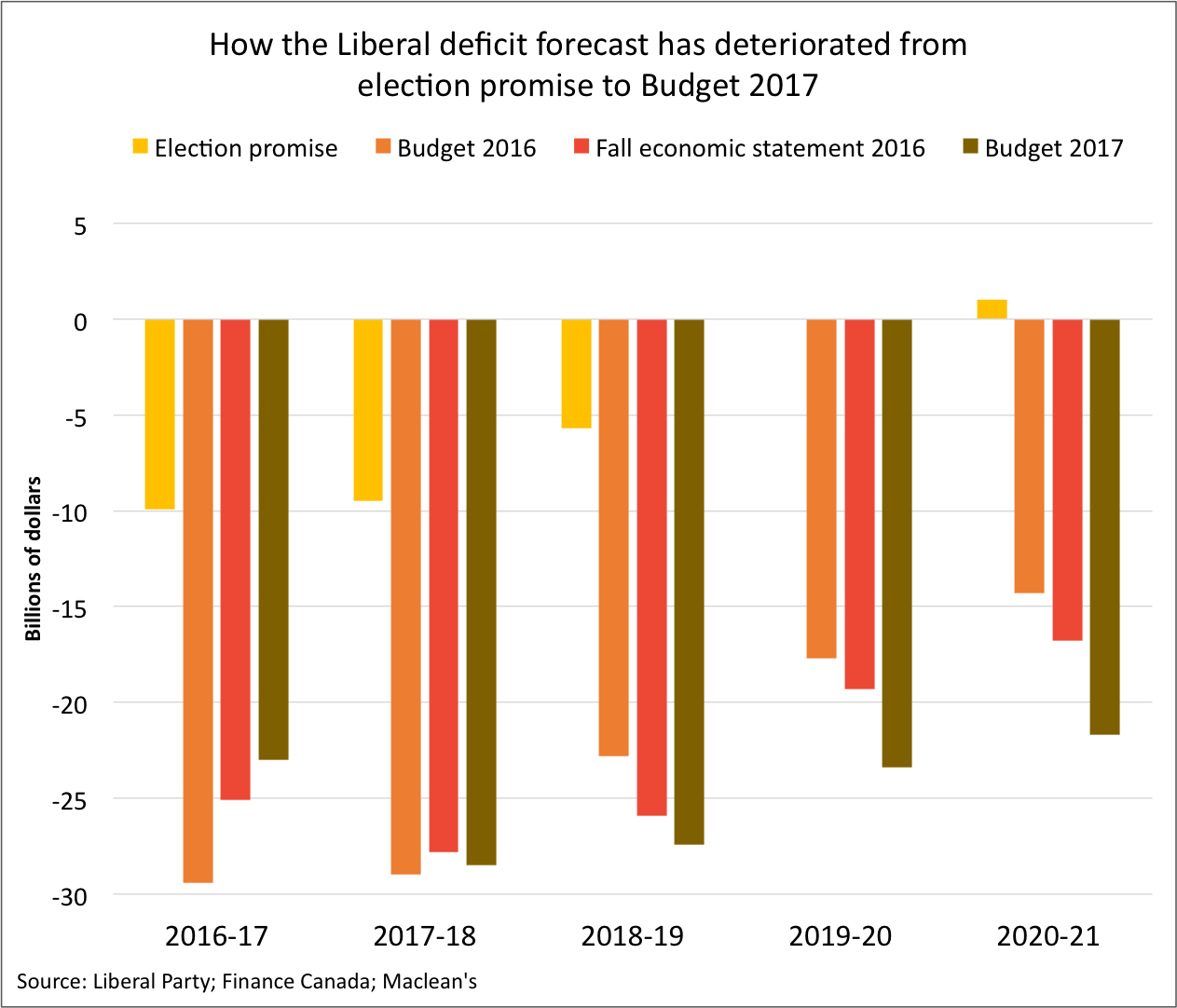

The previous Harper government shares some responsibility for what the Trudeau government is embarking on now. It had already played footsie with industrial policy. It perfected the art of doling out taxpayer money to favoured sectors, and used the language of levers and buttons in its own budgets. The Trudeau government simply picked up the thread and put some serious (borrowed) coin behind it, with its big-innovation, big-infrastructure plan racking up $145 billion in deficits over six years.

There are any number of reasons why Canadians should be wary of the government’s central planning approach to the economy, aside from the obvious question of whether we can afford it.

Given that McKinsey’s fingerprints are all over the budget, it’s worth remembering that when it comes to dishing out advice, the firm has a less-than-stellar track record. A few years ago U.S. investor and highly-regarded author Barry Ritholtz summarized the multitude of instances where McKinsey strategists were embroiled in financial messes around the globe—the firm was once described as “the company that built Enron” and its advice has been connected to numerous corporate failures. “Indeed,” Ritholz wrote, “wherever there has been a financial disaster in the world, if you look around, somewhere in the background, McKinsey & Co. is nearby.”

READ MORE: The control freak budget

Another problem is the challenge governments have always faced when they try to select winning companies and industries while avoiding losers. It’s incredibly difficult and there’s an overwhelming likelihood that you’re going to get it wrong. For instance, there’s a section in the budget about creating a supercluster around artificial intelligence, one of the brightest and shiniest sectors going at the moment. Yet lines from the budget like this, “Activity needs to remain in Canada to harness the benefits from artificial intelligence,” embody the problem with the industrial policy approach. You can deploy the force of government to try to build a domestic industry that develops the raw tools of artificial intelligence, but there’s no certainty of success, and in doing so you risk squeezing out entrepreneurs and companies who might otherwise have imported those tools from abroad and used them in ways you can’t now even imagine.

That table about company market caps referred to above is another case in point. You’ll note the government chose 2001, after the giant tech bubble of the late 1990s had imploded, as its starting point, thereby overlooking a period when the biggest companies in the land were all tech firms. Go back just one or two years earlier and Cisco and Intel would have made the cut, too, yet both technology companies are now worth half of what they were back then. It’s a reminder that many of yesterday’s winners are today’s losers, just as many of today’s winners will turn out to be losers tomorrow. But we don’t know—can’t know—which they will be, and trying to stage-manage the economy as if you do is dangerous.

For all the talk of fostering superclusters and creating new companies, it should be noted that there’s very little in the way of new financial resources to back that up in the budget—despite the big deficits. For instance, the government says it will invest $950 million over five years to support “superclusters,” but the vast bulk of that money is repurposed from last year’s budget, with the remainder scraped from “public transit and green infrastructure” funding allocated in the 2016 fall economic statement.

In that way, what mattered more on Wednesday than the dollar figures in the budget, was the government’s unabashed commitment to trying to direct the economy from above—and the absolutism with which it believes these policies will pay off. At least, that’s the plan.