Another omnibus budget bill and a test of Parliament’s will

The information commissioner expresses serious concerns, to which Parliament might now shrug

Aaron Wherry

Share

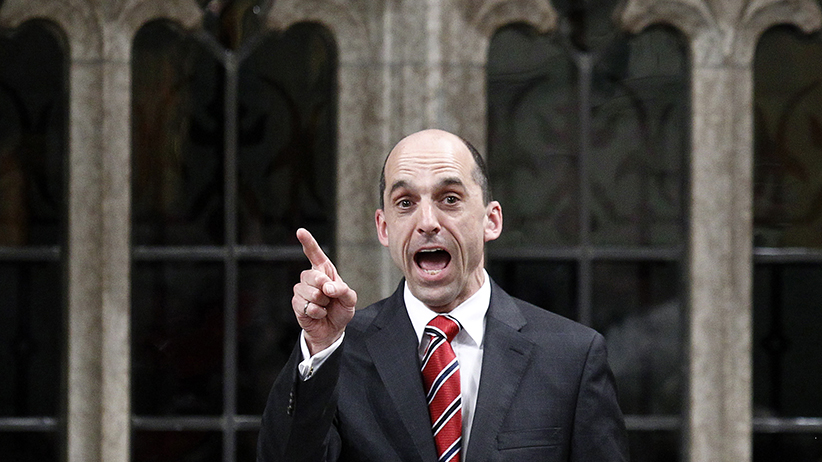

Charged yesterday with facilitating the illegal destruction of government records, Public Safety Minister Steven Blaney stood and invoked nothing less than the “will of Parliament.”

“We are proud,” he said, “to make sure that the will of Parliament and this country is respected.”

The will of Parliament. That near-holy principle of the legislature’s supremacy. The profound expression of the nation through its elected delegates. It is this, apparently, that Blaney and the Conservative government are proud to defend and uphold.

More specifically, the government is apparently proud to use a budget implementation bill—Bill C-59, officially dubbed Economic Action Plan 2015 Act, No. 1—to retroactively exempt the long-gun registry from the Access to Information Act. It is proud to do so despite the existence of an outstanding request for information from that registry, one filed in 2012 before the registry was abolished, and despite the information commissioner’s finding that the government did not fully comply with that request and despite the commissioner’s having written to the government to suggest it investigate whether the RCMP illegally destroyed records that were relevant to that request.

The actual expression of Parliament’s will to which Blaney referred would presumably be the passage of the Ending the Long-gun Registry Act, the bill that was to officially abolish and delete the registry. That bill passed into law on April 5, 2012. But the changes in C-59 would actually be retroactive to Oct. 25, 2011, the day the Ending the Long-gun Registry Act was first tabled, when it was officially nothing more than a 22-page stack of paper. So not only would the government retroactively reinterpret the will of Parliament, but it would retroactively birth that will into existence on an earlier date. (If Parliament was already considered a perfunctory check on legislation, now it would be made official.)

Whatever compliments the government might be due for chutzpah and creativity, the information commissioner is rather unimpressed.

“The proposed changes in Bill C-59 will deny the right of access of the complainant,” the commissioner ventured in a letter to the Speaker of the House this week, “it will deny the complainant’s recourse in court and it will render null and void any potential liability against the Crown.”

As well, “Bill C-59 sets a perilous precedent against Canadians’ quasi-constitutional right to know.”

The “will of Parliament” is perhaps best understood in the proactive sense of power—a setting forth of opinion, law or permission. Even if generally implicit, it is of course only by the will of Parliament that any government can continue in office.

But another way to view the notion, perhaps more relevant in contemporary discussions of our national legislature, is to understand the will of Parliament as what Parliament is willing to do and let be done: what its members are willing to let the government do with it, through it and to it.

It is here then that parliamentarians must ask themselves what they are willing to do, how far they are willing to let the government go, how much or how little they are willing to bless this place with a sense of self-respect.

Whatever Blaney’s declaration to the House on Thursday, the government’s deference to the will of Parliament is, at best, selective. Indeed, its disregard for the will of Parliament is happily advertised in television spots that herald policies that have yet to be adopted by Parliament—the hours of debate and study that Parliament is to expend reviewing such measures reduced to a fine-print afterthought. Surely even those MPs who sit behind the government might still wish to have their work as legislators viewed with slightly more respect.

As it is and as yet, it does not seem that Parliament is too excised by what so greatly concerns the information commissioner. So far this perilous precedent for Canadians’ right to know, this apparent undermining of an investigation into the RCMP’s compliance with the Access to Information Act, has merited only three questions over the course of two sessions of question period, all three of those questions posed by Liberal MP Wayne Easter.

While the government dismisses the information commissioner’s concerns entirely and the RCMP insists it did nothing wrong, this would still seem the sort of thing that deserves a comprehensive parliamentary hearing. If the will of Parliament is anything to take seriously, the ethics committee would be convened and the commissioner invited to appear. The public safety minister and the RCMP commissioner would be summoned to answer for the force’s actions. The justice minister would be called to explain why he has not responded to the commissioner’s submission to him that the law was violated. All relevant documentation would be demanded and reviewed and a full airing of the facts would be had.

Instead, this particular portion of C-59 is scheduled to be looked at by the finance committee, where it will apparently be studied alongside all of the tax and fiscal measures that the committee has given itself all of eight hours to review.

As if the 41st Parliament, a parliament about parliament, hadn’t given everyone enough to lament already. This would be a last hurrah, a farcical victory lap for the much-maligned.

Indeed, if parliamentarians did wish to be taken seriously, if the will of Parliament was more than a perfunctory principle, MPs would simply refuse to allow this issue to be dealt with through a budget bill.

There would seem to be questions here about an individual’s right to demand information from his or her government, the government’s handling of that request, the actions of the RCMP, the proper expression of Parliament’s power and the legitimacy of retroactively rewriting law, but a thoughtful MP needn’t even begin to ponder those questions before deciding that nothing to do with access to information and the long-gun registry should be included in a budget bill under the heading of “Economic Action Plan 2015.” That to include such amendments in a budget implementation bill is a perversion of the legislative process.

Oh, but we are so far past this sort of thing being a thing, aren’t we? Just last year, this Parliament passed budget bills that measured 380 and 478 pages respectively. Two years ago, this Parliament passed a budget bill that included an amendment to the Supreme Court Act, an amendment apparently intended to ensure the eligibility of Marc Nadon and an amendment that was, like the ill-fated appointee, subsequently ruled unconstitutional. This Parliament, and indeed all subsequent parliaments, might be hard-pressed to top the profound absurdity of that particular move and perhaps it is almost as absurd to suggest that now, at this late date, that members might assert themselves. That having recently deferred to the government on a decision about their own security and having cowered at the prospect of dealing with a fraught matter of law and society, that a decisive combination of opposition and Conservative MPs might make a small stand to insist that this matter be properly handled. But surely there should always be hope. Maybe tomorrow an idealistic Conservative backbencher will heed the long ago words of an idealistic Reform MP and object.

Otherwise, so long as the government is both proud of what it is doing and insistent that it has a responsibility to fill the airwaves and Internet with ads and infomercials to explain its doings to us, it should make a multi-million-dollar effort to explain this manoeuvre. Pierre Poilievre could be dispatched to another community centre, this time with copies of the information commissioner’s special report to thrust into the hands of passersby and he could explain point-by-point why it was nothing to worry about and completely fine to deal with through a budget bill with cursory study.

The will of Parliament, however strongly or weakly expressed, should be held up for all to see.