How many ministers does it take to run a country?

How many ministers do we really need?

Minister of Justice and Attorney General of Canada Peter MacKay snaps a photo of the media as he sits beside Minister of Environment Leona Aglukkaq, left, and Minister of Public Works and Government Services Diane Finley during a cabinet group photo following a swearing in ceremony at Rideau Hall in Ottawa on Monday, July 15, 2013. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Sean Kilpatrick

Share

With the recent addition of Erin O’Toole to the ranks of the officially honourable, the Conservative government now has 40 ministers, equal to the most to ever serve at the same time—a total of 40 having once previously been sworn in when Brian Mulroney became prime minister in 1984.

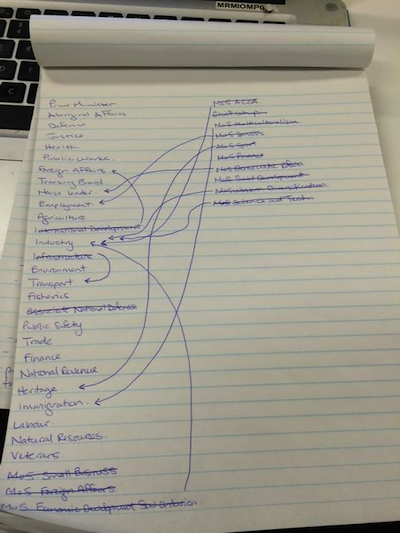

That seems like a lot of ministers. So the other day, for kicks, I decided to see how far I could reduce the federal ministry, within some vague sense of reason. From the 40 ministerial portfolios, I got the list down to 24. Mostly that involves getting rid of all ministers of state (I figure their portfolios can be handled by an existing minister), eliminating the associate minister of defence, taking away the whip’s ministerial status and folding two ministerial positions into others (international development to foreign affairs and infrastructure to transport). That would get us back to the same number of ministers that Diefenbaker had in 1961.

For another perspective, here is a redesign that gets us down to 25 ministers, with six junior ministers.

For another perspective, here is a redesign that gets us down to 25 ministers, with six junior ministers.

If we further decided that there would be one parliamentary secretary for each minister, the roster of secretaries could be reduced from 30 to 24. In all, that would take about 21 people off the payroll (the whip would keep his salary as whip).

(Is the government still offering rewards for money-saving ideas? If so, to whom should I direct this suggestion? Also: If the number of civil servants can be reduced, should the number of ministers follow suit?)

Stephen Harper was once quite proud to be surrounded by just 26 other ministers, but though he’s managed to keep his actual cabinet around that size, his generosity and desire to see his colleagues celebrated has slowly overwhelmed his interest in efficiency, gradually increasing the number of ministers to 40.

Of course, the money saved here would be, in the grand scheme of the federal government, basically insignificant. Perhaps more important, cutting the roster of ministers and parliamentary secretaries would add talent to the backbench, creating 21 more backbenchers capable of doing smart, interesting and independent things as MPs who are not directly in the employ of the government—21 more MPs who would be less beholden to the government and thus freer to scrutinize the government’s actions.

Sheer size is perhaps not the best measure in this regard. The number of ministers has gradually increased, but so has the number of MPs. And so, measured as a percentage of the House of Commons, Harper’s 40 is less than Mulroney’s 40: Harper using 12.98 per cent of the House, Mulroney using 14.18 per cent. But even on that score, the increase in ministers seems to have outpaced the increase in MPs. The first cast of 13 ministers in 1867 comprised 7.18 per cent of the House. Wilfrid Laurier got to 7.98 per cent, Robert Borden to 10.21 per cent, Pearson to 10.6 per cent, Trudeau to 13.12 per cent. From there it has sort of levelled off: Mulroney, Chrétien, Martin and Harper peaking respectively at 14.18 per cent, 12.6 per cent, 12.66 per cent and 12.98 per cent. From 1867 to 1984, did governing become a larger and more complicated task? Probably. But then if that’s the case, perhaps the cabinet and legislature should have grown in the same proportion: if governing requires more ministers, holding government to account should require more MPs.

If the number of ministers holds at 40 after this year’s election, the addition of 30 new seats will reduce the ministerial share of the House to 11.83 per cent. Coincidentally, a total of 24 ministers would amount to 7.1 per cent, back almost precisely to where we began.

Brent Rathgeber is rather unimpressed with the current ministerial count and he is preparing to table a private member’s bill that would attempt to limit the number of ministers, perhaps to something like 25 or 30. The bill won’t have any real chance of passing the House, but it could at least be a point of reference and discussion and the mechanics will be interesting to consider.

The Brits actually have a law that at least limits the number of people who can receive ministerial and secretarial allowances. They end up with the equivalent of 84 ministers and parliamentary secretaries, though that’s in a House of 650 members.

If we are to have 40 ministers we might at least demand that they make greater effort to justify their salaries. We could, for instance, consider the use of parliamentary secretaries to answer questions in QP to be only acceptable as an absolute last resort—there being so many ministers, and parliamentary secretaries having basically no responsibility for government policy. I’m also told by my elders that in days of yore, the dates and times of cabinet meetings were publicized and reporters were allowed to gather outside those meetings and so ministers leaving those meetings were compelled to go past those reporters, sought-after ministers having to decide whether they wanted to stop and take questions or be filmed walking away from said questions. I’m not generally a fan of shouting (it seems rude and I’m a bit of a low talker), but in exchange for getting to be called “honourable” for the rest of your life, you should be exposed to as much public accountability as possible.