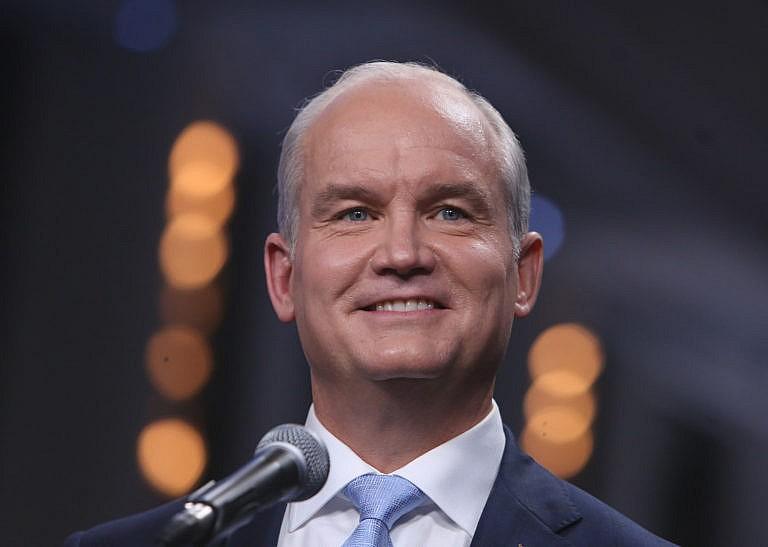

Federal leaders debate: Could it be Prime Minister Erin O’Toole?

Stephen Maher: Trudeau badly needed to paint him as a scary guy. But helped along by the other leaders, O’Toole came across as cheerful—even prime ministerial.

O’Toole speaks to the media following the federal election English-language leaders debate in Gatineau, Que., on Sept. 9, 2021 (Fred Chartrand/CP)

Share

Things are looking even better for Erin O’Toole on Friday morning than they were on Thursday, and they were looking pretty good then.

You never know how these things will land until the polls come in, but it sure looks like his chances of becoming prime minister went up during the only English language debate on Thursday night.

Not only did he put in the debate performance he wanted to do, but Justin Trudeau failed to do the same, and a perceived slight by the moderator looked to pump up the campaign of Bloc Quebecois Leader Yves-François Blanchet, which could be bad news for the Liberals.

On Wednesday night, for the French language debate, Trudeau came to pick a fight and managed to do so, getting good jabs in at his chief rivals. On Thursday night, for the English language debate, Trudeau came to pick a fight and failed to do so. Hamstrung by the moderation—which Liberals angrily objected to on social media—the format, or his own shortcomings, he did not manage to do what he desperately needed to do: paint Erin O’Toole as a scary guy.

O’Toole, on the other hand, did what he needed to do, which is seem not scary. Throughout, he managed to be as reassuring as a glass of milk, serene and cheerful, excited to tell you about his plans, like an unusually ambitious economic development officer for a suburban Toronto municipality. He lowered the temperature, smiled, talked vaguely and optimistically and was able to avoid tough questions or parry them with a smile.

He was helped by the other leaders, in particular Singh, who kept attacking Trudeau, as he has done effectively throughout the campaign, as inauthentic, a phony who is all talk and no action.

“How do we trust a government that takes a knee one day, and Indigenous kids to court the next?” Singh asked. Trudeau flatly denied that the government is taking Indigenous kids to court, which Cindy Blackstock swiftly fact-checked on Twitter.

Trudeau’s one good shot was delivered to Green Leader Annamie Paul, entirely the wrong target, when said he wasn’t a real feminist. “I think Ms. Paul, you’ll perhaps understand that I won’t take lessons on caucus management from you,” he said, which is true, actually, since she lost one of three caucus members and seems not be talking to the other two. But it seemed impolitic for Trudeau to be dragging the first black female leader in her first minutes of the debate.

I was anticipating that Trudeau would score some points in his head-to-head debate with O’Toole on climate—since the centrepiece of O’Toole’s climate plan is an impractical-sounding carbon consumer reward system—but Trudeau couldn’t make any clear points, and O’Toole succeeded in shutting him down by pointing out that Trudeau has failed to meet his own targets.

O’Toole’s cheerful, calm disposition, and the format, made it difficult for Trudeau to score points on him, which he urgently needed to do with the election tied with 11 days to go, so O’Toole was able to get his message out, and even when it is similar to the message delivered by his predecessors, he delivers it in a more cheerful way.

On the oil industry and emissions, for instance, he delivered the ethical-oil argument—that Canada should not cut exports because nasty countries will just sell more oil—but more nicely than Andrew Scheer did.

On the question of his vote against the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, O’Toole explained that he was concerned about the prior and informed consent clause would make it hard to develop partnerships with Indigenous communities, which he said is his goal. This has to do with whether pipelines can be pushed through over the objections of First Nations—which might sound bad—but he is talking about partnerships and making progress, and he is smiling and somehow believable.

What we are seeing, I think, is a hard-working politician, someone who has spent many long hours learning the lessons of political communication. He looked and acted more prime ministerial than Trudeau did, and that augurs well for him and ill for Trudeau.

The election isn’t over, but it almost is. Advance voting begins today. Millions may vote by the mail. Trudeau will surely try to pivot before long to making pleas to soft New Democrats, but it will get harder to make that work as more votes go into boxes.

And the Blanchet story—which looks set to take off in Quebec today—could put the Liberals on the defensive in the territory they desperately need if they are to stave off a Tory challenge.

The short version is that moderator Shachi Kurl referred to Quebec legislation on secularism and language as discriminatory, which he was able to object to as Quebec bashing, and which many Quebecers may see as an insult.

Quebec is famously electorally volatile, and there is a hardened consensus around the desirability of these laws in the province, so it is likely to arouse passions there, which ought to help the Bloc, hurt the Liberals, which helps O’Toole.

Before the debate, I thought Trudeau looked likely to squeak back in with a reduced minority. After the debate, I am not so sure.