The Liberals are spending far more than they said they would

Economist Stephen Gordon unpacks the federal government’s finances to explain why the deficit is so much bigger than Trudeau promised

Canada’s Prime Minister Justin Trudeau (L) and Finance Minister Bill Morneau walk to the House of Commons to deliver the budget on Parliament Hill in Ottawa, March 22, 2016. (Patrick Doyle/Reuters)

Share

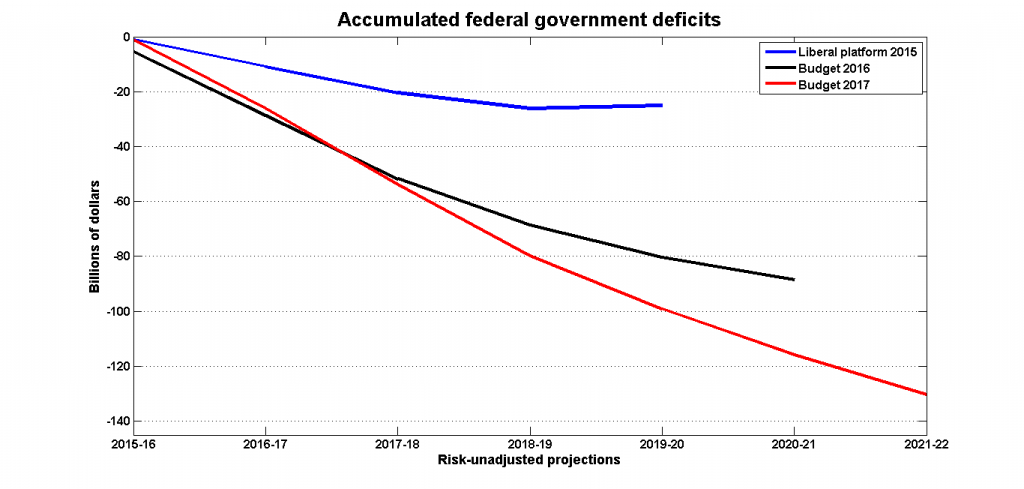

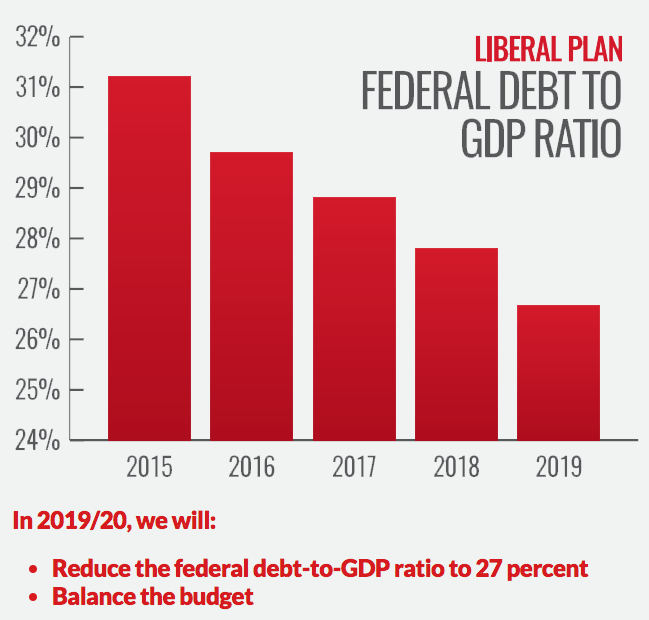

The Liberals campaigned on a platform that promised a short-lived period in which their government would run ‘modest’ deficits. After incurring an accumulated deficit of $25 billion over 2016-19, the Liberals promised to return the budget to balance by 2019-20, the fourth year of their mandate. Instead of balancing the budget throughout their mandate—as both the Conservatives and NDP were promising—the Liberals would hold fast to two ‘fiscal anchors’ of their choosing, as they stated in their “costing plan” in 2015:

Yeah, well, not so much:

Neither of those promises is going to be delivered by 2019-20. According to the latest long-term projection provided by the Department of Finance, these objectives are scheduled to be achieved sometime between 2040 and 2050, which means approximately never. Fortunately for the cause of responsible governance, the federal Liberals have accepted responsibility for their failure to keep their word and are sufficiently shamefaced about the whole mess that there’s not much point in investigating the matter any further.

Just kidding! The Liberals are blaming everything and everyone else—including their Conservative predecessors—for the current state of public finances. So in this post, I’m going to try and figure out what happened.

READ MORE: The unmasking of Bill Morneau, caped budget crusader

The Liberals’ standard talking point is that the larger-than-expected deficit is a result of slower-than projected economic growth. But as far as I can tell, this is only a partial explanation, accounting for roughly one quarter of the deterioration in the federal budget balance. Roughly three quarters of the increase in the federal deficit can be explained by the fact that the Liberals are spending much more than what they said they would during the election.

The idea that poor economic performance is to blame for the deficit is difficult to reconcile with near-record-low unemployment rates, but there is still something to it. The 2015 LPC platform used the economic baseline set out in the Conservatives’ 2015 budget. As new data have come in, these projections—based on an average of private-sector forecasts—have been revised steadily downwards. But it’s important to understand how and why this has happened, and it comes down to making the distinction between nominal and real GDP.

READ MORE: A budget for make benefit glorious economy of Canada

When it comes to forecasting the revenue numbers that show up in the budget, nominal GDP is what matters: economic activity measured in current dollars. But an increase or a decrease in nominal GDP doesn’t necessarily reflect an increase or decrease in real economic activity—things like output, employment and household purchasing power. If the only thing that happened in the economy was that the prices of all goods and services went up, nominal GDP would increase, even if real economic activity stayed constant. Of course, the mirror scenario can also happen: an increase in real economic activity will increase nominal GDP, even if prices stay the same.

It’s useful to break down nominal GDP into its real and price components:

Nominal GDP = Real GDP x Price Level

When referring the GDP, the price level is often referred to as the ‘deflator’: to obtain real GDP, you ‘deflate’ nominal GDP by dividing by the price level—the ‘deflator’. If you take the growth rates of both sides of this equation, this relationship becomes

Growth in Nominal GDP = Real GDP Growth + Inflation

So there’s a two-part explanation to lower-than-projected growth in nominal GDP:

- Lower-than-expected growth in real GDP

- Lower-than-expected growth in the price level (or deflator)

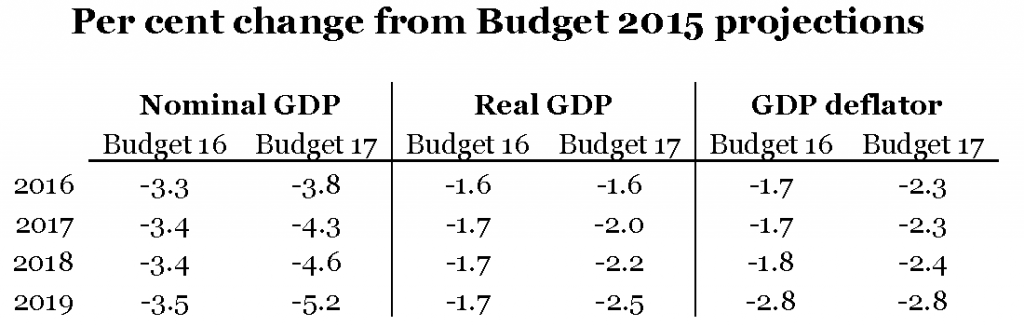

It turns out that the price level story is actually more important than the one involving real economic activity. According to the most recent projections in the 2017 budget, most of the shortfall in nominal GDP is due to lower-than-projected inflation. Real GDP over 2016-20 is projected to come in 2.1 per cent lower than projected in 2015, while the GDP deflator is expected to be on average 2.4 per cent less than projected. The average shortfall in nominal GDP is the sum of these two components: 2.1 + 2.4 = 4.5 per cent.

(My excel file going through the various projections – with risk adjustments stripped out – is available here.)

There’s no great mystery about the effects of lower-than-expected real GDP growth on the budget balance: it leads to lower revenues and a deteriorating budget balance. But what about lower-than-expected inflation rates in the GDP deflator?

I think it’s easier to explain and understand if we ask the opposite question: what if inflation had come in higher than expected? If this were the case, then the government would be well within its rights to say something like this:

“We committed ourselves to purchasing a certain quantity of goods and services. The price of respecting this commitment has gone up more than we expected, and so we will be spending more than we projected—in nominal terms—to carry out our obligations. Higher inflation has also increased revenues above what had been projected, so this increase in nominal spending will not affect the budget balance in real terms or expressed as a percentage of GDP.”

There is nothing wrong with this sort of statement: what matters is real economic activity, and adjusting nominal expenditures in response to a pure price change is the proper thing to do.

But of course, that’s not what has happened: prices are coming in lower than expected. If you think—as I do—that the above statement makes sense in a context of higher-than-expected prices, then this is what you’d expect a government to say when prices come in below projection:

“We committed ourselves to purchasing a certain quantity of goods and services. The price of respecting this commitment has gone up less than we expected, and so we will be spending less than we projected—in nominal terms—to carry out our obligations. Lower inflation has also reduced revenues below what had been projected, so this reduction in nominal spending will not affect the budget balance in real terms or expressed as a percentage of GDP.”

Here is where the Liberals have tripped up. Instead of adjusting nominal spending down as inflation came in below projection, the path of nominal expenditures has been revised upwards in the first two Liberal budgets. Real levels of spending are higher than what the Liberals had promised.

READ MORE: 21 ways the federal budget will hit Canadians’ wallets

We now have to make a detour to note that the Liberals never actually set out what their revenue and spending commitments were in the last election. Their costing was set out in terms of the 2015 budget balance baseline (with adjustments), where items were added and subtracted to obtain a projection for the budget balance over 2016-20: no numbers for revenues or spending were provided that could be used as a basis for comparison with what came later.

In this excel file, I’ve tried to fill that gap, using the original 2015 budget baseline as a starting point, adding the Liberals’ risk adjustments, and then classifying the various proposals in the Liberal platform as either revenue or expenditure measures. For example, the canceling of the Universal Child Care Benefit is a revenue increase (the UCCB was a tax credit), the introduction of the Canada Child Benefit is a revenue decrease (the CCB is also a tax credit), the ‘Middle Class Tax Cut’ is a revenue reduction, and so on. The final budget balances reproduce the projections in the Liberals’ platform. (Some of these revenue/spending classifications are judgment calls, so if you see an item that I’ve misclassified, I’ll be pleased to make the necessary changes.)

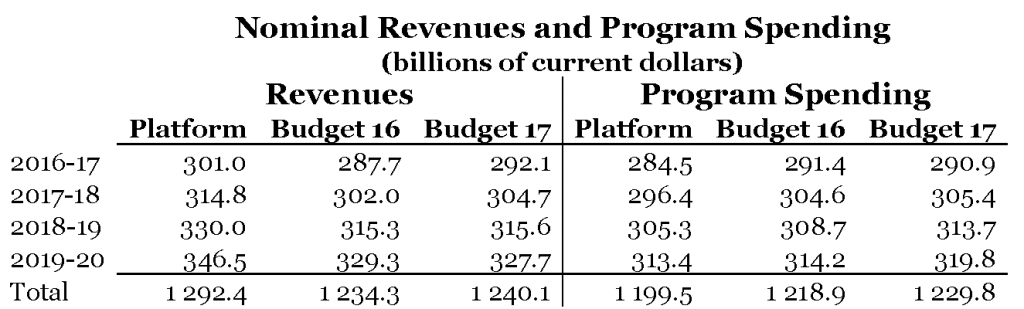

This table summarizes nominal revenue and spending projections in the Liberal platform and in their two budgets:

Although I’ve broken the numbers down for each year, I’ll try to keep things as simple as possible by talking only about the four-year totals for 2016-2020. Total nominal spending as projected in the 2017 budget ($1 240.1 billion) is four per cent less than the total projected in the platform ($1 292.4 billion)—a gap slightly less than 4.5 per cent average shortfall in nominal GDP. On the spending side, the projected total of $1 229.8 billion is 2.5 per cent higher than projected in the platform.

Let’s look at the primary balance, which is the difference between revenues and spending—that is, the balance with debt service payments excluded. Revenues in the 2017 budget are $52.3 billion lower than in the platform, and spending is $30.3 billion higher, for a total reduction in the primary balance of $82.6 billion over 2016-20. The Liberal government would presumably argue that since most of this reduction—52.3 out of 82.6, or 63 per cent—comes from revenue side, revenues are the principal culprit in the deterioration of the federal budget balance.

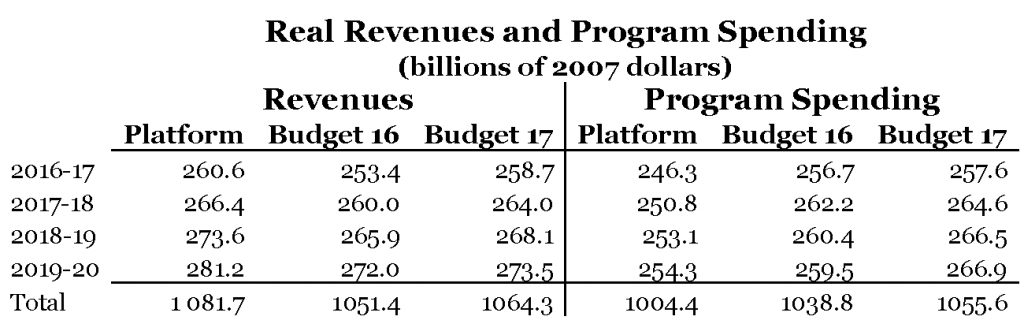

But this story leaves out the part where prices undershot the projection. If the Liberals wanted to maintain their spending commitments in real terms—which is what matters—they should have reduced nominal spending below the targets set out in their platform. Because prices came in under projection, and because nominal spending has actually increased over the platform commitments, real federal government spending is running 5.1 per cent higher on average than what the Liberals promised during the election.

By the same token, lower-than-projected prices also means that the shortfall in real revenues is less than the shortfall of nominal revenues. Real revenues are running 1.6 per cent on average below projection, compared to 4 per cent in nominal terms.

In constant 2007 dollar terms, the 2016-20 primary balance is $68.7 billion below what was projected in the Liberal platform. Of that, some $51.2 billion, or about three-quarters, is due to real expenditures running above projection. Translated back to nominal terms, the Liberals are spending about $15 billion dollars a year more than they had promised to spend during the election campaign. Put another way, the Liberals would have to cut spending by about five per cent a year to bring real expenditures down to the commitments in their platform. And put yet another way, the 2016-20 federal deficit would be reduced by two-thirds if the Liberals had stuck to their spending commitments in real terms.

It should be noted that the conclusion here is not that spending has increased under the Liberals: the obvious retort to that claim is that increased spending is a campaign commitment that the Liberals have a mandate to carry out. The point is that real federal spending has increased to levels significantly greater than what the Liberals had promised in 2015.

MORE ABOUT THE FEDERAL BUDGET:

- What Trudeau says his government has achieved in 2017 so far, annotated

- Proposing amendments isn’t Senate activism. It’s the Senate’s job.

- The problem with involving the PBO in elections

- A budget for make benefit glorious economy of Canada

- Bill Morneau’s budget speech for two Canadas

- An ode to the Canada Savings Bond

- The unmasking of Bill Morneau, caped budget crusader

- The control freak budget