The truth about Trudeau’s tax cuts

How Trudeau’s plan takes from the rich and gives to the almost-as-rich

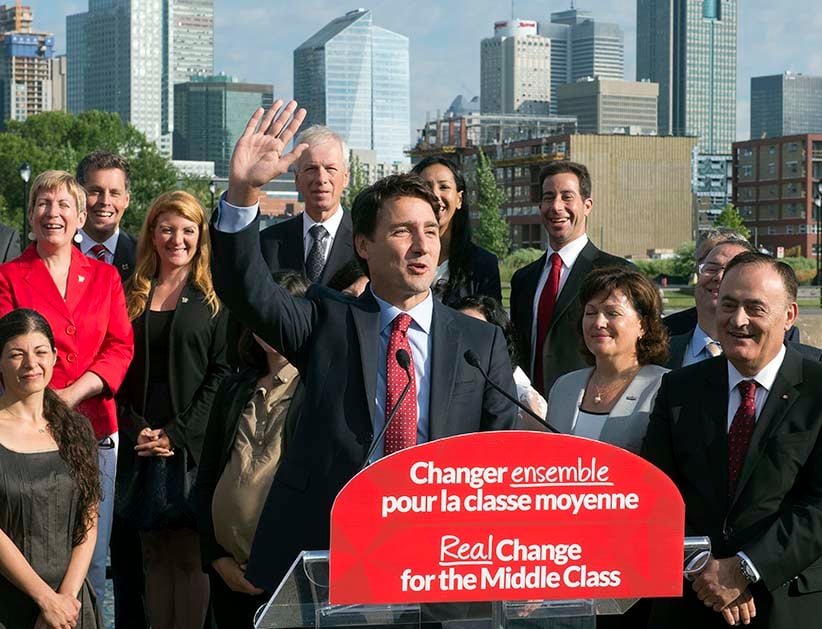

Federal Liberal leader Justin Trudeau speaks to supporters Monday, August 10, 2015 in Montreal. (Ryan Remiorz/CP)

Share

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has lots of election promises to keep, but none more pressing than his pledges to cut taxes for the middle class and hike them for the rich. The closely linked commitments featured in almost every Trudeau campaign speech, and probably helped him pull votes from both his main adversaries. Some former Conservative supporters would, naturally, have liked the sound of the middle-income break, while others who leaned to the NDP might well have been attracted by the tax-the-rich part.

Trudeau signalled how important the tax promises were when he declared on Oct. 9—just as the campaign entered its home stretch—that the very first legislation a Liberal government planned to table in the House would be to push through the changes. “You’ll see more money on your paycheques right away,” he said. The Liberals touted the tax cut as being worth up to $670 per person, or a tidy $1,340 per year for a two-income family.

It sounds like a nice chunk of cash. But a closer look by an independent economist shows that few tax-paying households will reap anywhere near that much. Trudeau vows to trim the federal tax rate on income between $44,700 and $89,401 a year, from the current 22 per cent to 20.5 per cent. At the same time, the rate on income $200,000 and over will rise from 29 per cent to 33 per cent. In a neat bit of tax-design symmetry, the higher top bracket is calibrated to bring in the entire $3 billion needed to pay for the lower-middle bracket.

What might surprise many middle-income voters, though, is how the $3 billion in tax savings will be distributed. David Macdonald, senior economist at the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, an Ottawa-based think tank, used a Statistics Canada model to project how the Liberal proposal would affect families at various income levels. To get the maximum benefit, an individual must be making nearly $90,000, and having two earners in a family, both making that much or more, generates the highest savings. That leaves the tax cut for those who make considerably less looking very modest.

Macdonald has forecast the benefits for what Statistics Canada calls “economic families,” which include couples, with or without children, and single parents. The roughly 1.6 million families making about $48,000 to $62,000 will see their tax bills trimmed by, on average, just $51, while those making $62,000 to $78,000 will save $117. The tax savings rise steadily with family income, to $521 on average for families in the $124,000 to $166,000 range, and $813 for those making $166,000 to $211,000. Above that level, the new, higher top tax bracket erases any savings the families got by paying less tax on income in the reduced middle tax bracket.

Macdonald dismisses the excuse that income-tax cuts almost automatically amount to more for those earning more money. “The smart folks at [the Canada Revenue Agency] can design you a tax to do whatever you want it to do,” he says. Even calling the Liberal proposal a middle-class tax break is debatable, Macdonald says, since those who stand to benefit the most—families in the $166,000 to $211,000 income range—are in the top 10 per cent of Canadian earners. He calls those familes “upper middle class.” (As for families earning more than $211,000, Macdonald says they will pay, on average, $2,912 more in federal tax.)

Although Macdonald doesn’t like the way the planned tax changes fail to funnel savings further down the income spectrum, he does approve of other policies Trudeau has promised. The Liberal platform’s most ambitious single measure is a plan to combine a raft of existing federal payments and tax breaks for parents into a single one, to be called the Canada Child Benefit (CCB). “The total revamping of the child benefit system will certainly benefit lower-income households with children substantially more than it will benefit anyone else,” Macdonald says.

During the election, Trudeau sometimes mentioned the CCB in the next breath, after his high-profile tax changes, although it’s more complicated, and thus harder, to pitch in a campaign. The CCB promises more money to all families with kids whose incomes fall below $150,000. For a two-parent family, with two children, making $90,000, the tax-free monthly CCB cheques will amount to $5,875 a year, or $2,500 more, the Liberals say, than the same household gets under the parcel of benefits introduced or modified by Stephen Harper’s Conservatives.

Sherri Torjman, vice-president of the Ottawa-based Caledon Institute of Social Policy, calls the CCB “extraordinarily important.” Torjman, who is not a Liberal but served on an economic advisory council that Trudeau met with regularly before the campaign, urges critics to look at the tax and benefits policies as a package. “It will take at least a year, maybe two, but, at the end of the day, the middle-class household will certainly be better off,” she says. It seems some taxpayers who expected a big boost right away are going to be asked to be patient.