There’s no putting a shine on Canada’s fiscal picture

Bill Morneau’s ‘fiscal snapshot’ predicts a $343-billion deficit—nearly 16 per cent of the country’s annual GDP

Morneau takes part in a media lock-up for the federal government’s economic and fiscal snapshot (Sean Kilpatrick/CP)

Share

Finance ministers usually turn federal budgets into polished exercises in public relations. They show off their plans for the future, sprinkling new spending and tax credits among all of Canada’s regions and assorted interest groups. They stuff the boring fiscal tables at the back of unwieldy books, the covers of which feature smiling faces and sunshine. Bill Morneau’s economic and fiscal snapshot—tabled in the midst of a pandemic and riddled with gloomy projections asterisked by persistent uncertainty—doesn’t pretend the good times are here to stay. These are bad times, and everyone knows it.

Sure, this summer’s update makes a big deal of the billions in emergency spending that filled the bank accounts of workers without jobs and businesses with no revenue. And the fiction writers at the Department of Finance still invented characters—Nathan and Emily, parents of two young kids; Sammy, a restaurant owner; Anna, a post-secondary student—who illustrate the depth and breadth of the widespread federal economic bailout. Morneau was suitably optimistic on the floor of the House of Commons. “Canadians are resourceful. Canadians are resilient. Together, we will get through this and build a better, fairer, and stronger Canada,” he said. But the document he tabled is largely devoid of fanfare, and it’s easy to feel depressed even picking a page at random.

Here’s what passes for good news. Canada doled out the most direct fiscal support of any G7 nation, and the total dollar value of the economic response—including tax deferrals and liquidity support—is also tops among that group of countries. Yet coming out of 2020, federal projections say Canada will have the lowest net debt-to-GDP ratio of any G7 nation. The feds also claim their response plan substantially softened the hit to GDP growth, the unemployment rate and the prospects of Canadian families: “Despite clear challenges individual households may be facing, overall Canadians’ household finances appear to be holding up well so far.”

RELATED: Did Bill Morneau even sleep a wink?

But those numbers won’t make many headlines.

The word of the day is uncertainty, which the fiscal snapshot says is “magnified to unprecedented levels.” The finance department’s survey of private sector economists in May had “shifted dramatically” from mid-March, when the coronavirus hit Canada hard. Those early forecasts predicted flat GDP growth in 2020. May’s survey, by contrast, produced predictions, on average, of a seven per cent drop. As the government’s forecasters attempted to predict what’s next, they added their own estimates to the private sector group’s best guesses—which varied wildly for the remainder of 2020.

A resurgence of the virus would, of course, “severely hamper the economic recovery.” The feds gamed out two scenarios—”uneven and gradual recovery” and “virus resurgence”—in addition to the private sector numbers. The first scenario envisioned a world in which repetitive peaks in virus transmission leave households hesitant to visit most public spaces, and force businesses to remain shuttered because they can’t afford the cost of re-opening. The knock-on effect of more persistent, and permanent job losses produces an estimated 9.6 per cent decline in real GDP growth.

Finance planners also looked at a scarier future, in which uncontrolled virus transmission re-emerges later this year and coincides with the next flu season. Even with improved preventative measures and contact tracing, more prolonged shutdowns would hit Canada with a “deeper and longer-lasting negative impact.” Canada’s GDP would theoretically decline by 11.2 per cent in 2020, and GDP growth would fall “below that of even the most pessimistic private sector forecast by the end of 2021.”

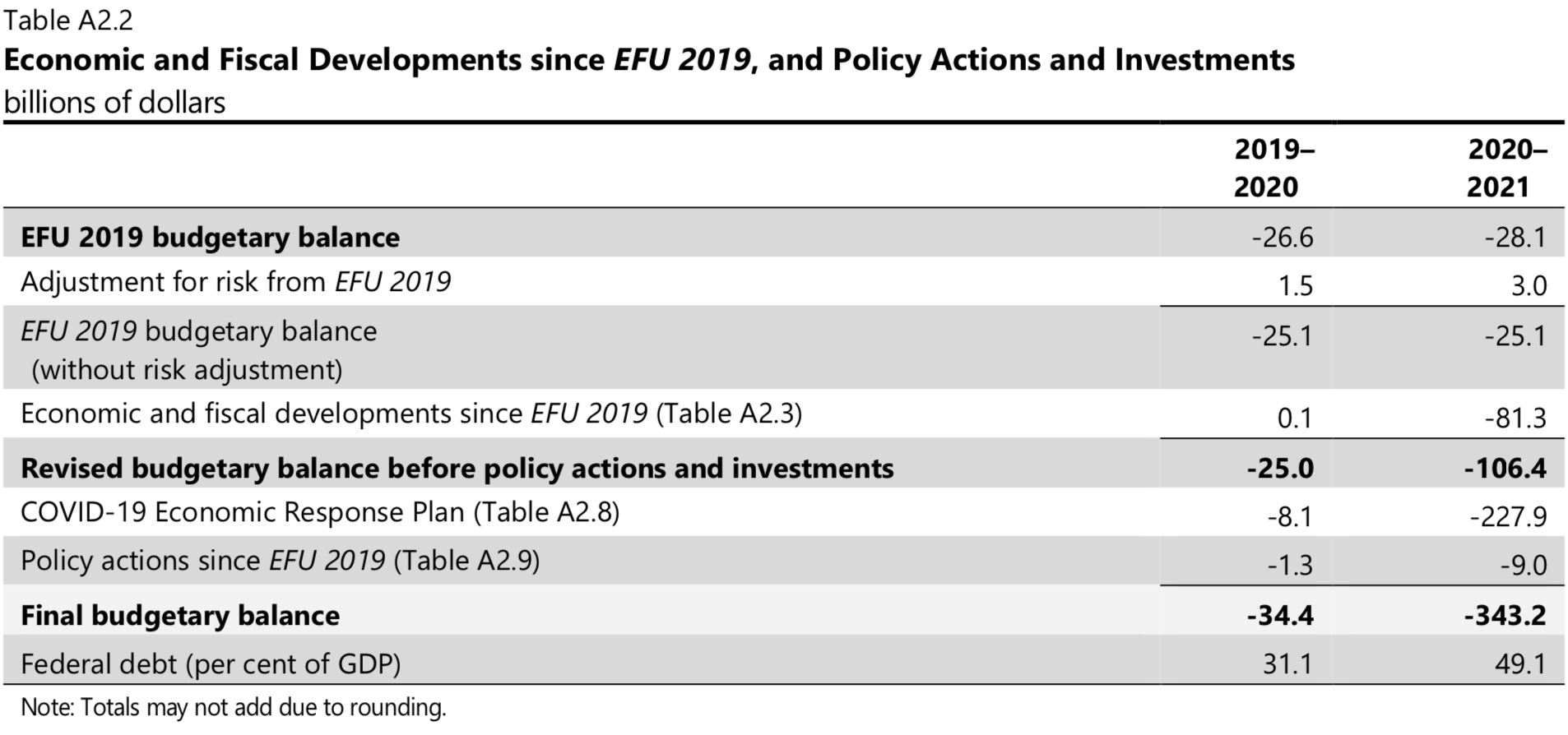

The big number, the kind of figure that ends up at the top of news stories, is this year’s projected deficit. The parliamentary budget officer, Yves Giroux, had pegged it only several weeks ago as higher than $250 billion. Various private-sector economists had predicted up to $300 billion in red ink. The fiscal snapshot offers an even higher number: $343.2 billion, a consequence of vast sums of spending and similarly eye-popping totals in foregone revenue. Canada’s federal debt-to-GDP ratio had hovered just above 30 per cent for the most recent Liberal term in office. That rate is expected to leap to 49.1 per cent this year, and total debt will surpass the trillion-dollar mark that will end up in bold on newspaper front pages. In 2018-19, long before the pandemic unleashed economic chaos on the global economy, Canada’s annual deficit represented 0.6 per cent of GDP. This year, that will shoot up to 15.9 per cent.

RELATED: Why Canada might need a temporary COVID-19 tax and repayment fund

A general rule of thumb in budget literacy is that the deeper within the document a table resides, the more revealing it is of government finances. True to form, the 121st page of the fiscal snapshot is where the devil is hiding in the details. Table A2.2 points out the $227.9 billion in emergency spending: the CERB, the federal wage subsidy and all the other money earmarked for workers and employers. But just above that line on the same table is another hit to the federal bottom line: $81.3 billion in “economic and fiscal developments” since last year’s fiscal update.

Think of that as code for the $40.8 billion in income tax revenue projected last fall that, due to “developments,” federal coffers won’t see—$30.9 billion of which is personal income tax. Excise taxes, import duties, carbon pricing, EI premiums and other revenues, including crown corporations’ net profits, are all revised downward. The government’s financial position is now in a different universe than just a few months ago. Last year, the feds collected $341 billion in revenue and racked up $375.3 billion in expenses. Those projected numbers for 2020-21 have now fallen to $268.8 billion and risen to $612.1 billion, respectively.

In terms of adjectives, “unprecedented” barely covers it. But there is one more piece of good fiscal news. All that new debt is pretty cheap. Because interest rates have made borrowing historically cheap, the feds will actually pay $4.3 billion less in charges on the billions of new debt they’ve accrued than they had projected to pay on what they’d already borrowed.

Just don’t expect that silver lining on Page A1 of your local daily.