Trudeau’s unrequited love for China

Paul Wells: The Canada-China relationship is now a smoking rubble. It would be great if the Prime Minister had something to say about it.

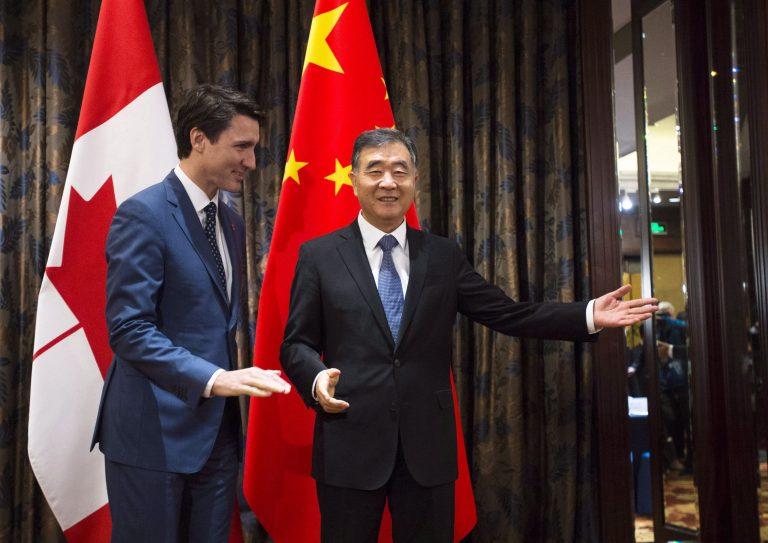

Trudeau meets with Chinese Vice Premier Wang Yang in Guangzhou, China, on Dec. 6, 2017 (THE CANADIAN PRESS/Sean Kilpatrick)

Share

Writing stuff down is almost always a bad idea. Justin Trudeau had been a candidate for the federal Liberal leadership for six weeks when he published a column in the Financial Post, in November of 2012, decrying Stephen Harper’s clumsiness on China. “The Conservatives kicked off their stewardship of the relationship with unhelpful sabre-rattling, followed by a stubborn silence,” he wrote. “Recently, they have made attempts at courtship, but China’s leadership has a long memory. Influence and trust is built through consistent, constructive engagement.”

“Further, the Conservatives have developed their approach to Asia, such as it is, behind closed doors. This is a mistake. Where is the leadership to explain to Canadians why this relationship is so important, to engage Canadians in the conversation, to make us aware of the opportunities?”

Fast forward to today, and the smoking rubble of the Canada-China relationship under Trudeau. China will be pulling its ambassador, Lu Shaye, from Ottawa, within days. The symmetry is nice, even if no other part of this situation is: Canada has had no ambassador to Beijing since John McCallum resigned in January for—misstating? Stating too plainly?—Ottawa’s view of the Meng Wanzhou imbroglio. Canada and China, two important countries with many decades of complex interaction, are reasonably close to having no diplomatic relations. The foreign minister can’t get her calls returned.

I’m not particularly in a mood to blame the Prime Minister for this turn of events. It’s easier to argue that Beijing’s disdain these days is a badge of honour. The bitter, sustained Chinese retribution for the arrest of Meng was something nobody could have foreseen a few years ago, and I’ve written before that, despite the grandly weary complacency of some old Ottawa China hands, the Trudeau government has essentially handled that stink-bomb of a file more honourably than if it had tried somehow to warn Meng away.

Still, one can only marvel at the scale of the mayhem on a relationship Trudeau once viewed as a field ripe for glory. “From minerals to energy, from education expertise to construction, we have a lot of what China needs,” he wrote in that 2012 op-ed. “We should be creative when thinking about what a trade deal with China could look like. … What if our goal was to become Asia’s designer and builder of livable cities? What if we got our world-class financial institutions and pension funds together with our world-class engineering and construction industries to secure a leadership role for Canada in Asia’s growth.”

READ MORE: Huawei’s Meng Wanzhou: The world’s most wanted woman

This was, back in the day, of more than anecdotal interest to the young Liberal leadership candidate. Trade was the “one big thing” that could ensure “the next wave of growth for the middle class.” Trade with the United States wouldn’t do it. Fortunately, “China is scanning the world for acquisitions like a shopper in a grocery store.”

This was no arena for the squeamish. “China, for one, sets its own rules and will continue to do so because it can,” Trudeau wrote. “China has a game plan. There is nothing inherently sinister about that.”

Unfortunately, it turns out that most of the creativity in Canada-China relations has come from China lately, and it involves throttling canola imports, threatening pork and beef imports, and holding former Canadian diplomats incommunicado while accusing Canada of indulging “western egotism and white supremacy.”

To a great extent, if the bilateral relationship is as bad as it’s ever been, it’s because of something that happened five days before the Financial Post published Trudeau’s manifesto in 2012: Xi Jinping became general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and chairman of the Central Military Commission. Xi has been ruthless about consolidating power within the Party, aggressive in pursuing Chinese interests globally, and disdainful of foreign criticism. “China is still open for business but it no longer welcomes foreign ideas,” a 2018 CSIS report, China and the Age of Strategic Rivalry, says. Indeed, the report adds, China is “persistent in disputing the global rules put in place by powers it perceives as in decline.”

This is a big development in global affairs, a major event in recent world history, and it’d be great if the government of Canada had something to say about it all. Instead, as somebody once wrote about a previous government, the Trudeau Liberals have developed their approach to Asia, such as it is, behind closed doors. This is a mistake. Where is the leadership to explain to Canadians why this relationship is so important, to engage Canadians in the conversation, to make us aware of the dangers?