What’s the winning recipe for the Conservatives?

Philippe J. Fournier: Who is leading the party won’t matter as much as who can get the vote out in the next general election

MacKay and Harper address the media at a news conference in Ottawa on Oct. 16, 2003 (CP/Jonathan Hayward)

Share

The Conservative Party of Canada leadership race is now in full swing with the main candidates tweeting anti-Trudeau comments and policy statements in hopes to both rile up support from current Conservative Party members, and sell new membership cards to build a fresh horde of supporters for the June 2020 leadership convention in Toronto.

With news this week that former Stephen Harper cabinet minister John Baird would not run for the leadership, it appears likely that this race will come down to either Peter MacKay or Erin O’Toole (although, as Paul Wells wrote earlier this month, Conservatives should perhaps take a second look at candidate Marilyn Gladu).

Among the daily tweets sent by the MacKay communication team over the last week, we notice MacKay has focused mostly on current events, such as the anti-pipeline blockades and protests, Justin Trudeau’s trip to Africa, the ratification of CUSMA (or NAFTA 2.0), and the importance of conscience rights for medical practitioners.

PM Trudeau's pandering has hit a new low. After pathetic efforts to buy African votes to sit on the UN Security Council, he bows to Iranian Minister Zarif, the regime responsible for the deaths of 57 Canadians. 1/2

— Peter MacKay (@PeterMacKay) February 15, 2020

MacKay’s main rival, Durham MP Erin O’Toole, also expressed his desire to see an end to the blockades (“I’ll stand firm against eco-extremists“), but has mainly focused his message on safe conservative talking points, such as describing himself as “The anti-Trudeau”, and detailing his plan to defund the CBC (by as much as 50 per cent according to this video he posted).

It should be noted, however, that O’Toole has been using language noticeably more combative than MacKay: “Take Canada back”, “Enough is enough”, “It’s time we start fighting”, and “I’m not the media’s candidate” (Incidentally, in his latest column on the matter, Stephen Maher described O’Toole’s words about the media favouring MacKay as “codswallop”—a word I honestly had to look up, and which will now be part of my regular lexicon.)

The anti-Trudeau.

Join us and let's take Canada back: https://t.co/Jx7lTV0Xxe pic.twitter.com/FcIJxqaERw

— Erin O'Toole (@erinotoole) February 9, 2020

So what is the Conservative winning recipe in 2020? In January, I wrote an analysis of a Léger poll that focused on what Canadians thought about policy and personality traits for the new Conservative leader. For instance, the data suggested the CPC would take a tremendous risk by electing a leader with social conservative views—a significantly greater fraction of respondents, including CPC supporters, believe that the party should elect a pro-choice and LGBT-friendly leader.

However, while these policy choices have garnered a lot of media attention (and will undoubtedly storm back during the next general election campaign), they may not matter much, if at all, to the CPC leadership race. According to Frank Graves of EKOS Research Associates, “the party knows where it is and how it got there. It’s the strategists and media who are living in something that looks a lot like a state of denial.” Commenting on its latest data of the Canadian electorate, Graves states that: “As in the U.K. and the U.S., authoritarian or ordered populism has polarized Canada into two incommensurable camps.”

Such polarization is neither new to Canada nor to many western democracies. But with little (and narrowing) common ground to be found between liberals and conservatives—in broader terms than just parties—the big tent coalitions that shaped Canada’s political landscape for most of the 20th century have, it seems, mostly disappeared.

If tribalism has overshadowed policy in the minds of many voters, the winner of the next federal election may not depend much on who leads the main parties, but rather could come down to which team can get its vote out the most—and in the right places.

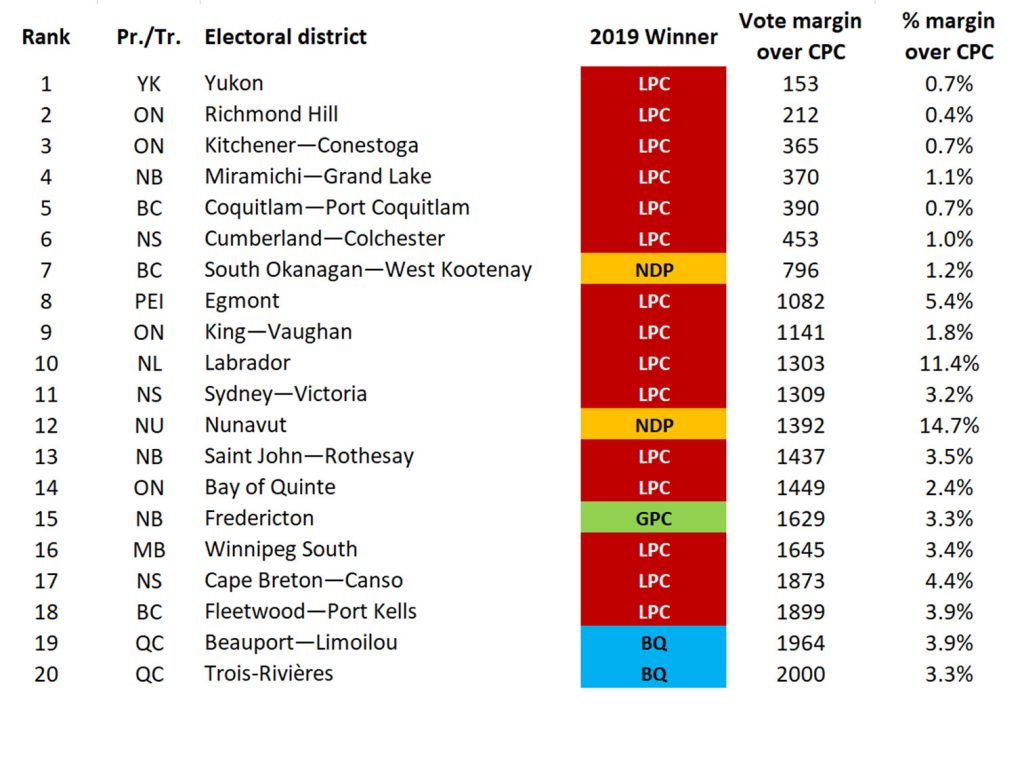

Case in point: In last fall’s federal election, the Conservatives lost 20 electoral districts by 2,000 votes or fewer. Here is the list ranked by the vote margin over the CPC:

Among this list, 15 districts went to the Liberals, the NDP and Bloc took a pair each, and the Greens won Fredericton. (Admittedly, Nunavut is the odd district on this list, since even though the CPC lost by 1,392 votes to the NDP’s Mumilaq Qaqqaq, those votes add up to a significant 14.7 point gap between the NDP and CPC). From this list alone, the CPC lost these 20 districts by a combined margin of fewer than 25,000 votes (compare this with the 6.2 million votes cast for CPC candidates). Had the Conservative ground game been able to flip these districts, the Liberals and Conservatives would have finished one seat apart in the final tally. Trudeau’s minority would have been much less stable and Andrew Scheer would probably still be CPC leader.

Among this list, 15 districts went to the Liberals, the NDP and Bloc took a pair each, and the Greens won Fredericton. (Admittedly, Nunavut is the odd district on this list, since even though the CPC lost by 1,392 votes to the NDP’s Mumilaq Qaqqaq, those votes add up to a significant 14.7 point gap between the NDP and CPC). From this list alone, the CPC lost these 20 districts by a combined margin of fewer than 25,000 votes (compare this with the 6.2 million votes cast for CPC candidates). Had the Conservative ground game been able to flip these districts, the Liberals and Conservatives would have finished one seat apart in the final tally. Trudeau’s minority would have been much less stable and Andrew Scheer would probably still be CPC leader.

Instead, the Liberals won by a margin of 36 seats and the Conservatives pushed Scheer out the door.

The point of this column isn’t that policy does not matter to Canadian voters. But with political polarization on the rise in Canada, parties will assuredly find that the largest pool of accessible voters cannot be found within your opponents’ ranks, but among Canadians who stayed home on election day—roughly a third of eligible adults. The ground game, and a detailed analysis of precious voter data, may matter far more than many would like to believe.